In this author interview, we speak to Sharon Crozier-De Rosa about her new book, Shame and the Anti-Feminist Backlash: Britain, Ireland and Australia, 1890-1920, which examines the use of shame as an emotional tool in this highly divisive period for gender politics in and across these three countries. In the piece, she discusses the colonial and transnational dynamics of anti-suffrage movements, women’s militancy, her archival research in the Women’s Library and the continued significance of shame to understanding feminism today.

Author Interview: Q&A with Sharon Crozier-De Rosa on her book, Shame and the Anti-Feminist Backlash: Britain, Ireland and Australia, 1890-1920 (Routledge, 2018)

Q: Could you introduce your new book Shame and the Anti-Feminist Backlash?

Shame and the Anti-Feminist Backlash is a transnational history of emotions, (anti-)feminism and nationalism. It is a study of the emotional tactics used by women in the attempt to prevent their own enfranchisement. In particular, it is an examination of the use of shame as an emotional tool in the highly divisive realm of gender politics in and across Britain, Ireland and Australia between 1890 and 1920.

The phenomenon of women opposing their own political advancement is puzzling. As such, it is often misunderstood or, given the eventual success of the ‘votes for women’ campaign, dismissed as irrelevant. In this book, I look not only at the reasons why anti-suffrage women assumed the position they did – a stance that placed them on the losing side of history – but I also examine the emotional strategies they adopted.

Published in the year that sees Britain and Ireland celebrate the centenary of the granting of the female franchise, the book casts light on the women who feverishly opposed organised feminism. It showcases the diversity of the politics of womanhood. It is compelled by questions such as: why were women leading such a vitriolic backlash against the campaign for women’s advancement? What had they to gain from participating in this very public, very bitter campaign? What emotional tools did they deem appropriate to police womanhood? And why was shame a tool in gender politics?

Q: What is sometimes obscured in histories of the suffrage movement is the imperial context in which it emerged and developed. Could you discuss some of the colonial and transnational dynamics that your book draws out in their complexity?

The politics of empire shaped the experiences of suffragists and anti-suffragists alike in all three sites examined in the book. Imperial ties connected women across Britain, Ireland and Australia, and women in each country referenced each other’s campaigns, whether such connections were welcome or not. Whether loyal or disloyal, each group of national womanhood had to frame their aspirations by referencing existing assumptions: for instance, about their country’s position on the hierarchical imperial spectrum or about the nature of British or non-British values.

For example, women at the centre of a vast imperial network were under pressure to represent imperial values, such as ‘civilisation’ and ‘respectability’. Publicly aping the habits and duties of men threatened Britain’s reputation as global upholders of those values. In the far-flung peripheries of empire, reluctant women voters – those who had opposed their own enfranchisement – were dedicated to voting in a way that upheld Australia’s reputation as a loyal member of the empire’s family of nations. In an increasingly fervent anti-colonial nationalist setting, Irish women were embroiled in vitriolic debates about whether or not to ‘beg’ the virulent British coloniser for a right to vote in an enemy imperial parliament.

Shame politics connected each site but were manifested differently in each country. Whereas Australian women worked to deflect any accusations of shameful conduct on the part of their young, white, aspiring nation, women in Britain felt that to bring shame on the relatively insignificant colonies meant something very different to dishonouring the centre of a vast imperial network. Irish women, on the other hand, struggled with the burden of whether or not joining their British sisters in demanding the vote in an enemy British parliament would bring more shame to a colonised Irish manhood and Irish nation.

There have been a number of fabulous studies that have examined suffrage politics in their transnational settings, whether from the point of view of the imperial centre, the perspective of those involved in feminist campaigns in the Antipodes or in tense anti-colonial sites like Ireland. My experiences as an historian of nationalist, imperial and gender politics, born in Ireland, now working in Australia, have inspired me to look for connections between diverse groups of national womanhood, while also respecting the uniqueness of different gendered cultures. This book, rather than collecting essays on different groups of national suffragists or plotting one national group’s interactions with the international movement, examines three groups of political women, connected by virtue of their opposition to the female franchise and their relative positions on the British imperial spectrum, to see if they forged emotional strategies that were national or transnational in character.

Q: The granting of suffrage is often narrated as an outright triumph for women. But your scholarship underscores the extent to which many women felt ambivalent, apathetic or even hostile towards their enfranchisement. Is it important to underscore this complex, perhaps uncomfortable, diversity to challenge the notion of suffrage as being experienced as an unequivocal victory?

I remember first encountering passionately-articulated female opposition to suffragism that I was extremely uncomfortable with a number of years ago. As I read through the novels of an extraordinarily successful late Victorian and Edwardian female writer, Marie Corelli, to complete my PhD thesis on bestselling fiction and a history of women’s emotions in the early 2000s (subsequently published as The Middle Class Novels of Arnold Bennett and Marie Corelli, Mellen, 2010), I could not help but be disturbed by the glaring anti-feminist sentiment infusing her writing. Her books cast light on a world where feminist shaming, and sometimes woman hatred, were accepted and well-practised customs.

I was driven at the time to investigate why an eminently successful, independent, professional woman felt the need or desire to issue such vehement condemnations of female suffragists, and more generally why prominent women employed emotional tactics in such a reasoned and calculating way against other women.

In examining the views of women labelled ‘anti-feminist’, I wanted to help broaden current understandings of the sheer diversity of late Victorian and Edwardian conceptions of female citizenship – all from the point of view of women writers and activists participating in that mass public debate.

Q: Shame and the Anti-Feminist Backlash draws on archival research carried out in the Women’s Library based here at LSE (previously at London Metropolitan University). What role did the Library play in your research and did you discover any particularly memorable objects?

This book could not have been completed without the invaluable collections housed in the Women’s Library, one of the world’s preeminent collections of women’s archival materials.

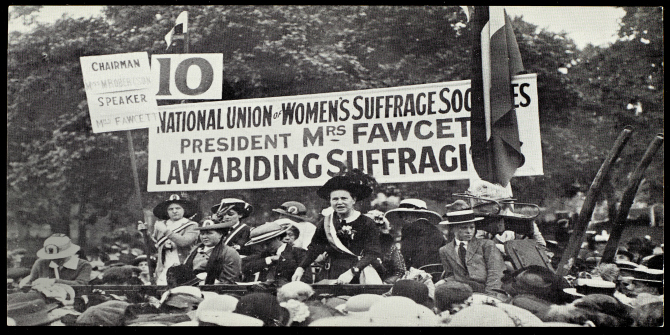

In the first place, anti-suffragists lost the war on suffrage. As such, they are frequently overlooked by historians – their passionate campaigns, including their cutting attacks on suffragists, often act as an embarrassing reminder of an archaic, obsolete and ultimately failed movement. Yet, those compiling what became the Women’s Library did not overlook the contributions of these women to the highly volatile gender politics of the early twentieth century. Therefore, in a trip to London from Australia in the early 2010s, I was able to access preserved copies of the official organ of the National League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage (NLOWS), the Anti-Suffrage Review, which has been invaluable for my study of the British anti-suffragist mindset and political strategies.

Secondly, the Women’s Library has been a fabulous source of suffragist materials, including some intriguing ephemera. I have been able to access everything from flyers by constitutional suffragists condemning the actions of militants to a copy of Florence Claxton’s The Adventures of a Woman in Search of her Rights, complete with Claxton’s original drawings.

I know that throughout its existence the Women’s Library has struggled to survive, given the funding pressures placed on educational resources, but I am so happy that LSE has stepped in to save the collection. And now it is housed in an area of London renowned for its physical connections to the suffrage campaign, especially its militant side!

Q: Thinking about militancy, something your book discusses is the shame surrounding the figure of the violent or revolutionary woman, especially in the case of nationalist women in Ireland. Do you think any of the women in your book forged a ‘feminist ethics of violence’?

This is the issue that my book ends on. It is more of a question posed than answers given! It is also explored in greater detail in a book that I have co-written with Vera Mackie, due to be published in a few months, entitled Remembering Women’s Activism (Routledge, 2018). In sections of that book, we look at how militant women in various global suffrage and nationalist campaigns are remembered publicly, and according to the changing prerogatives of their respective nation-states.

The thing about constructing what might be termed a feminist ethics of violence is that the notion of women perpetrating acts of violence divides the feminist community almost as much – if not more – than the community of those not subscribing to feminist views. Violent women, then, fought on many fronts.

On the issue of whether or not militant or violent women affected any long-term transformation of gendered emotional norms, I find it useful to look at how Constance Markievicz has been remembered in postcolonial Ireland and in the state north of the border, Northern Ireland.

Markievicz was a nationalist, socialist and feminist politician and a soldier. She was a vocal advocate of women arming in defence of their country. She argued that British notions of sex segregation, enforced through the colonising process, had eroded Irish notions of gender equality – equality in militant as well as non-militant spaces.

However, I argue that, through her militancy, Markievicz did not succeed in transforming gendered emotional regimes. Instead, she and other women like her who persisted in fighting for a Republic on the whole island of Ireland have been perceived as a shameful and embarrassing reminder that the postcolonial Irish man once had need of his revolutionary sisters to help him win his war against the British coloniser. This can be seen via the ‘Poppet’ statue, for example. In 1998, a statue of Markievicz and her dog, Poppet, was erected outside a fitness facility in Dublin (right). It is a very tame, feminine portrait of the revolutionary with her domestic pet. Disarmed and domesticated – in the same year that the Northern Irish state that Markievicz had fought against was disarmed via the signing of the historic 1998 Good Friday Peace Agreement – the Poppet statue provides no evidence that its central subject has ever been anything but a sentimentally popular local heroine.

Go north of the border where a simmering sort of peace reigns and the need for the potential of the revolutionary woman still exists. As such, Markievicz and her warrior sisters continue to adorn the walls of West Belfast estates. We look at the many other ways Markievicz has been (mis)remembered in Remembering Women’s Activism.

Q: Your research explores shame as a ‘versatile political tool’ in the debates around women’s suffrage. Do you see shame as operating in notable ways in contemporary feminist battles too?

Yes, certainly. Shame is, in effect, the fear of being judged defective by an individual or group to whom one attaches value. It is the fear of doing something that causes that group to exclude or ostracise you. Therefore, as scholars of the emotion attest, shame is always present because as humans we always fear being excluded – of not belonging.

In November 2016, I wrote a piece for The Conversation that examined why feminists felt that it was OK to shame Hillary Clinton in the lead-up to the US Presidential Election. Clinton was shamed as every form of bad feminist. She was a bad pacifist feminist. She was a bad intersectionalist feminist. She was a sexist wife who joined in the slut-shaming of Monica Lewinsky after her affair with Bill. In that article, I asked if all this feminist in-fighting demonstrated that gender solidarity did not trump all, as many have triumphantly claimed. My response was: no, I think it confirms the opposite.

Woman shaming reveals – as it has since the earliest women’s rights movements – that the issue of gender solidarity is at the heart of the matter. Much of this shaming of women voters and women candidates, such as Clinton, is not about denying the notion of gender solidarity. Rather, it is about women attempting to construct a relevant and workable model of twenty-first-century feminism. In the case of Clinton and global feminist aspirations, it was about women trying to reach a consensus about what a female president should look and sound like. It was about defining the community of womanhood – and/or of feminism – to which women wanted to belong.

What I concluded in that Conversation piece was that if American women had had 44 female presidents to represent them, as men had had, then they would not have had need of this one woman – Hillary Clinton – to embody all facets of what has always been a highly diverse and fractured community of feminist womanhood.

Whatever we think about the desirability of feminist shaming, one good thing that has resulted from this campaign is the passionate body of debate centred on twenty-first-century feminist values – a body of debate that is reminiscent of that taking place a century ago!

This interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog. The images of the Constance Markievicz mural and statue were kindly provided by the author, Sharon Crozier-De Rosa.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Anti-Suffrage Postcard (LSE Library).

Find this book:

Find this book:

2 Comments