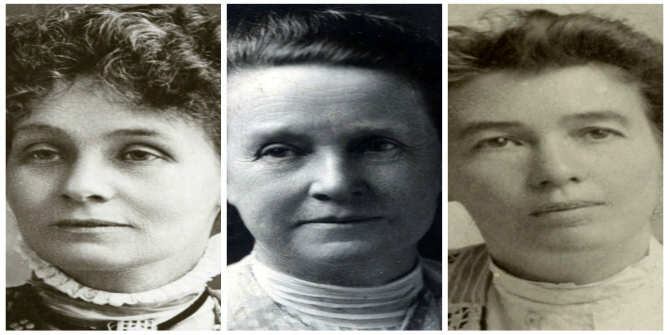

Image Credit: Emmeline Pankhurst, Millicent Garrett Fawcett and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

Image Credit: Emmeline Pankhurst, Millicent Garrett Fawcett and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

2018 marks the centenary of partial suffrage in Britain, when property-owning women over the age of 30 won the right to vote in parliamentary elections in the UK. To commemorate the historical link between LSE and the campaign for women’s suffrage, on 23 November 2018 the Towers at Clement’s Inn on LSE campus are being renamed Pankhurst House, Fawcett House and Pethick-Lawrence House after three important suffrage campaigners with specific connections to the School.

To celebrate the occasion, this feature offers an edited extract from the new book Remembering Women’s Activism (Routledge 2018, pages 22-24), by Sharon Crozier De-Rosa and Vera Mackie, in which they discuss the memorialisation of the non-militant and militant branches of the British suffrage movement, the establishment of The Women’s Library and the physical spaces of LSE that link these histories.

Preserving Their Own Memory: Constitutional Suffragism and the Fawcett Society

If you are interested in this book, it can currently be purchased directly from Routledge here with a 20 percent discount if you use the code FLR40.

If you are interested in this book, it can currently be purchased directly from Routledge here with a 20 percent discount if you use the code FLR40.

Public memorials to the non-militant branch of the British suffrage movement tend to evoke a sober sense of respectability that belies just how radical that campaign was seen to be in its own time. These memorials work to emphasize the constitutional movement’s reputation for dignity and decorum in the face of its militant counterpart’s lack of respectability.

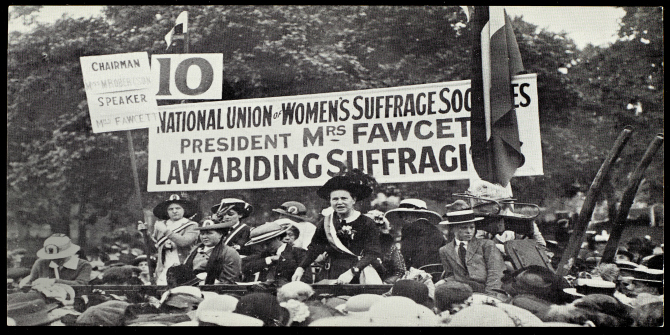

A number of plaques mark the former residences of Millicent Fawcett, leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). A blue plaque marks her former city home in London, making her one of a relatively small number of women to have been so honoured. Another plaque remembers her childhood home in Aldeburgh, Suffolk.[i] The memorial to Fawcett in Westminster Abbey’s St George’s Chapel surpasses all others for its evocation of a sense of stateliness and propriety.[ii] Sculpted by Sir Albert Gilbert (1854-1934) in 1887, the Abbey monument was originally dedicated to Fawcett’s husband, Henry Fawcett (1833-1884), philanthropist, academic, and politician. Decades later, in 1932, a much simpler and less imposing inscription and insignia to Millicent Fawcett were placed in roundels at each side of the central display. The inscription reads: ‘Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett 1847-1929. A wise constant and courageous Englishwoman. She won citizenship for Women.’ The insignia within the roundels represents the NUWSS and the Order of the British Empire. There are also small relief portraits of the couple.[iii]

Homage of Millicent is secondary to that of her husband but the Fawcett Society has transformed the monument into a shrine to the leading suffragist by conducting an annual pilgrimage. The Society, which traces its roots to ‘Millicent Fawcett’s and the suffragists’ successful parliamentary campaign for women’s right to vote’, was renamed in Fawcett’s honour in the 1950s. It identifies itself as ‘the UK’s leading charity for women’s equality and rights at home, at work and in public life’.[iv] Like so many organizations founded to commemorate the achievements of feminist activists in the past, the Fawcett Society invokes that past to inspire gender activism in the present. Its regular pilgrimages to Westminster Abbey affirm those temporal and political connections.

Image Credit: Millicent Fawcett’s Hyde Park address on 26 July 1913 (7JCC/O/01/177) (LSE Library/No Known Copyright Restrictions)

Image Credit: Millicent Fawcett’s Hyde Park address on 26 July 1913 (7JCC/O/01/177) (LSE Library/No Known Copyright Restrictions)

For the NUWSS, the collection and preservation of materials relating to the constitutional movement was a large-scale project. The NUWSS grew from an umbrella body that directed the activities of about seventy suffrage societies in 1909 to one coordinating 305 societies in 1911, a number that had swelled to as many as 400 by 1913.[vi] In 1926, in order to house the collection, the library of the London Society for Women’s Service was founded (previously the society had been called the London Society for Women’s Suffrage). In the 1950s, the organization became the Fawcett Society and the library was named the Fawcett Library. By the 1970s, the Fawcett Society found that it could no longer afford to keep the collection. This period saw the emergence of women’s and feminist history as an academic discipline. The Fawcett Library then moved to the City of London Polytechnic (later renamed Guildhall University). It served as a crucial resource centre for those feminist scholars emerging from the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s.[vii]

The Library’s holdings have since expanded to include materials related to the militant suffragist movement and to women’s history more generally. Indeed, it grew to become the UK’s leading women’s history archive and a world-recognized collection of women’s historical documents. Of interest to those researching the militant movement, it houses interviews with former suffragists and suffragettes (including those recorded by Brian Harrison over the years 1974-1981) and artefacts such as Emily Wilding Davison’s (1872-1913) purse and (much-discussed and debated) return ticket from the Epsom Race Course, a Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) tea service, and an impressive collection of suffrage banners.[viii]

As valuable as this resource has been to the memory of the suffrage movement and the writings of British women’s history more generally, it has struggled to survive. In the early 2000s, it was renamed The Women’s Library and moved into a purpose-built building connected to London Metropolitan University (previously Guildhall University), a move made possible by a £4.2 million Heritage Lottery Fund award. A decade later, when London Metropolitan University announced that it could no longer afford the upkeep of the library, closure was threatened again. The ‘Save the Women’s Library’ campaign resulted in the archive moving to the London School of Economics (LSE), where it was preserved as a distinctive collection. The LSE has capitalized on the fact that it now owns so many of the buildings that were important to the early-twentieth-century suffrage movement, particularly the militant campaign, to raise the public profile of remembering women’s activism, weaving together physical site, academic research, and public memory.[ix]

In 2014, the LSE and Arts Council England developed a new mobile phone application, ‘Women’s Walks’, which tracks users’ locations as they walk through London and downloads relevant images, audio clips, and other documents from their women’s history collection to users’ smartphones, allowing an interactive historical journey through the city.[x] Former WSPU offices, now LSE buildings, are features of these walks. The Women’s Library, which once preserved the memory of the constitutional suffrage movement, now perpetuates the memory of all facets of the suffrage movement. The physical sites connecting LSE to a suffragette past strengthen the ties that The Women’s Library now has with the history of militant feminism.

[i] Recently, the Fawcett Society lamented that only 13 per cent of London’s blue plaques commemorate women. The London Blue Plaques website states that London’s blue plaques scheme, founded in 1866, is believed to be the oldest of its kind in the world and its aims were to celebrate the diversity and achievements of London’s past residents, connecting buildings and people in the process. English Heritage, ‘Blue Plaques’. The Fawcett Society was responsible for placing another plaque to Fawcett on the wall of one of her old residences, this time her childhood home in Aldeburgh, Suffolk. The plaque reads: ‘60 years a campaigner for women’s suffrage/Millicent Garrett Fawcett 1847-1929 lived here/The Fawcett Society’. See Fawcett Society.

[ii] Of Fawcett’s Westminster Abbey memorial, fellow suffragist, Helena Swanwick (1864–1939) declared: ‘In an age much addicted to superlatives, in which so many nonentities are ‘‘too marvellous’’ and people leap into the limelight, and back again, with bewildering rapidity the slow, steady, persistent life-work of such women as Millicent Fawcett, demands of us a soberness of statement in accord with their character’. Helena Swanwick, I Have Been Young (V. Gollancz, 1935), quoted in Joyce Marlow, Suffragette: The Fight for Votes for Women (Virago, 2000), Appendices.

[iii] Henry and Millicent Fawcett, Westminster Abbey.

[iv] ‘Our History’, Fawcett Society.

[v] See Hilda Kean, ‘Public History and Popular Memory: Issues in the Commemoration of the British Militant Suffrage Campaign’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 14, Nos. 3–4 (2005), pp. 581–582.

[vi] Susan Kingsley Kent, Sex and Suffrage in Britain, 1860–1914, p. 197.

[vii] Jill Liddington, ‘Fawcett Saga: Remembering the Women’s Library across Four Decades’, History Workshop Journal, Vol. 76, No. 1 (2013), pp. 266–280.

[viii] A newspaper article reporting on the troubles facing the library in 2012 noted that, ‘[a]mongst its 60,000 books and pamphlets and 16,000 objects are texts that reflect the reach of women’s history from a 1695 text calling for the formal education of women to a first edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. These sit alongside papers belonging to romantic novelist Dame Barbara Cartland and signed biographies of Margaret Thatcher’. Added to this are key artefacts from the suffragist movement. See Rachel Cooper, ‘A Room of Her Own: The Battle for the Women’s Library’, Telegraph (UK edition), 8 November 2012.

[ix] As one recent LSE History blog post announces, the buildings in and around the building that now houses the former Fawcett Library – many of which are now owned by LSE – were favourite haunts of the suffragettes. In particular, the WSPU general office had been at 4 Clement’s Inn since 1906. One of the tea shops frequented by nearby WSPU activists was the Tea Cup Inn opened in 1910 on the ground floor and basement of 20 Kingsway, now LSE. The WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women, was printed in close-by St Clement’s Press on Clare Market until 1912. There is now a plaque to the memory of the WSPU headquarters there which refers to the ‘Suffragettes’, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, and to the editors of Votes for Women, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. ‘Suffragettes and LSE – early neighbours’, LSE History Blog.

[x] ‘LSE Library Announces Women’s Walks, An Interactive Historical Journey through London’s Streets’, LSE.

Note: This book extract gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. Thank you to the authors and Routledge for providing permission to publish an edited extract from the book.

18 Comments