In “Ambedkar in London”, William Gould, Santosh Dass and Christophe Jaffrelot offer a new collection exploring Dr B R Ambedkar’s education and political formation in the city. This is a valuable and unique contribution that expands our understanding of Ambedkar’s activities and experiences in London and their continuing legacies, writes Scott Stroud.

Dr Bhimrao R Ambedkar (1891-1956) is one of the most influential and intriguing figures in the 20th century. Many know this thinker and activist as one of the most prominent advocates for the rights of India’s millions of “untouchables” (now called Dalits, a self-chosen label), or as a chief architect of the Indian constitution. And most know about his education in the West, including degrees at Columbia University in America and at institutions such as the London School of Economics and Political Science in Britain. But what details can we discern should we want to dive into the specific contexts of his educational experiences, or his time in London during his youth?

Ambedkar in London focuses on Ambedkar’s education and political formation in Britain. It is unique in filling significant historical gaps and conceptually rich in what it leads us to think in terms of Ambedkar’s international contacts. It is a unique and valuable contribution to understanding Ambedkar.

The book’s focus is far from myopic, since the limiting of its attention to London covers an important series of visits and returns to the centre of British colonial power. The book divides into two parts, focusing on Ambedkar’s educational and political experiences in London (from 1917 to the early 1930s) and his continuing relevance in London in the form of contemporary struggles over his legacy and anti-caste mission. Both sections demonstrate the vital importance of London as a source and scene of importance for understanding Ambedkar’s development.

The first half of this book explores Ambedkar’s time in London. It starts with three excellent chapters on his wide-ranging education in the city. William Gould gives a thorough account of Ambedkar’s transition from New York to London in the summer of 1916, and the context and figures involved in his education at LSE. Ambedkar’s housing in London and his educational practices — including a mix of focus on Indian economics and the inherent internationalisation of discourses within London circles — come into focus in this well-researched chapter.

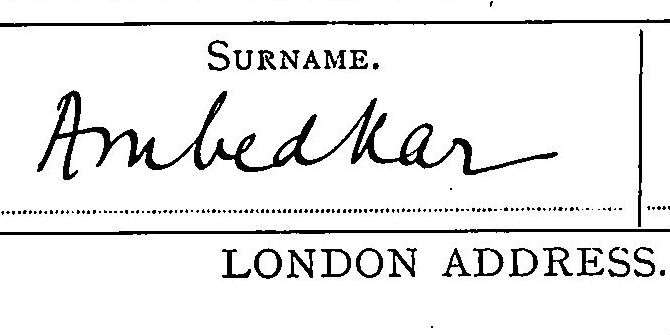

The exploration of Ambedkar’s education in London is deepened in the chapter by Sue Donnelly and Daniel Payne on Ambedkar as a student at LSE. Leveraging newly discovered archival records, Donnelly and Payne provide one of the most useful chapters in this volume. They dig as deeply as the records allow into the courses and instructors that likely influenced Ambedkar during his time at LSE. More than this, they paint an interesting picture of students from India who were influenced by LSE education around Ambedkar’s time there.

Of course, not everything in the air in London or in the current books was attended to by Ambedkar or lectured upon by his specific instructors; I found myself continually asking the further question — what did Ambedkar specifically hear in his courses from these professors? For instance, we do know with some precision what Ambedkar heard in his courses with John Dewey at Columbia. I am always interested to see how much detail we can get on what Ambedkar actually heard and learned from his time with other scholars and teachers in London. These two historical chapters, however, do an admirable job in adding new context to the claims about the importance of Ambedkar’s education.

The third chapter, by Steven Gasztowicz, explicates Ambedkar’s legal education in London. Most know that Ambedkar learned law at Gray’s Inn, but few offer many details about this education. This chapter is unique as it explains the context and content of legal education during Ambedkar’s time. Of particular interest to me was Gasztowicz’s explanation of the lecture topics that students had to choose from, and the communal dining in small groups that was required of students and members of the Inn to maintain an honourable standing. This meant that Ambedkar likely had intense social contact at regular intervals with other students and practitioners of the law through his connection with Gray’s Inn. If only we had a record of that dinner table talk!

Chapters by Jesús F Cháirez-Garza and Christophe Jaffrelot round out the first half of this volume with their chapters on Ambedkar’s participation in the Round Table Conferences and his evolving activist framework in the 1920s. These chapters serve the valuable purpose of reframing what we think of Ambedkar’s thought. Cháirez-Garza uses the context of the First Round Table Conference to demonstrate the fact that space mattered for Ambedkar’s advocacy. Put simply, Ambedkar was able to successfully make certain points about the removal of untouchability in forceful ways because he was making them in the internationalised — and largely caste-free — environment of London. Cháirez-Garza highlights the tensions Ambedkar felt in London, however, and their reflection in the press of the day: Ambedkar was seen as both a champion of the oppressed and as a divider of the Hindu community resisting the British, a point that Gandhi would exploit at the Second Round Table Conference and beyond.

Complementing this emphasis on Ambedkar’s internationalisation of the Dalit cause in London is Jaffrelot’s chapter. Jaffrelot argues a point that we all should realise, but that too many forgot: Ambedkar was a complex thinker and accounts that talk of ‘Ambedkar’s thought’ as a unified whole miss the richness, complexity and even contradiction within important parts of his texts, movements and speeches. Charting the evolution of Ambedkar’s advocacy and activism in the 1920s, including his returns to London, Jaffrelot shows how Ambedkar moved away from a position that sought reform within the Hindu fold and Sanskrit tradition to one that anticipates his explosive texts and speeches on leaving Hinduism in the 1930s.

The second half of the book moves beyond this history to consider the echoes of Ambedkar in contemporary London. This section focuses on the groups and activists his work has inspired or affected. Foremost are Ambedkarite and Buddhist associations that have made sure caste discrimination is foregrounded in discussions of social justice in London. A chapter by Santosh Dass, a leading thinker and activist among these movements, charts the history of Ambedkar-allied movements in Britain; in a separate chapter, she also chronicles the campaign to legally prohibit caste discrimination in Britain. Such movements, given their victories and setbacks, are an encouraging sign that Western institutions and academics are taking Ambedkar’s thought and the concerns of caste seriously.

Of particular interest to the story of Ambedkar in London is the chapter by Dass and Jamie Sullivan detailing the fight to get Ambedkar’s residence from 1920-22 at 10 King Henry’s Road designated a museum. The house, largely through the dedicated initiatives of Ambedkar groups in London, was purchased by the Government of Maharashtra in 2015. Further battles were necessitated to guarantee the status of the house as an official public museum dedicated to Ambedkar’s legacy and time in London. Dass and Sullivan offer a first-hand account of the process — and challenges — of convincing planning councils to sacrifice housing for history. Ultimately, Ambedkar’s cause won out in 2019 and the house has attained the status of a museum site.

The thematics of Ambedkar in London are pulled between two poles: Ambedkar’s efforts to internationalise the Dalit cause and his specific history in London. This is a productive, and interrelated, tension in this work. We see the confluence of these two strands in the final chapter by Kevin Brown. Many know about the correspondence between Ambedkar and the African-American thinker and activist, W E B Du Bois. Ambedkar seemed to be interested in linking the Dalit cause with international movements against racism. Brown does an admirable job showing how Du Bois’s engagement with Ambedkar extended beyond and before this interaction.

Brown’s chapter also charts the reasons why the African-American community did not fully see the Dalit problematic — as Brown documents, many African-American reports on the Round Table Conferences and other events related to India’s struggle for independence subsumed the known caste problem under the quest for national freedom from colonialism and racist oppression. This was the interlinked “dual victory”, one that placed freedom from caste oppression as an entailment of India’s political freedom. As Ambedkar sensed in his own time, such a linkage did not guarantee freedom from caste oppression. This chapter nicely concludes a book that does an admirable job filling in what we know about Ambedkar’s activities in London — and their continuing legacies.

Read more about Ambedkar and LSE and LSE and South Asia

To find out about LSE’s South Asia collections head to the LSE Library’s Traces of South Asia webpage.

This post was originally published on the LSE Review of Books blog. Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Thanks