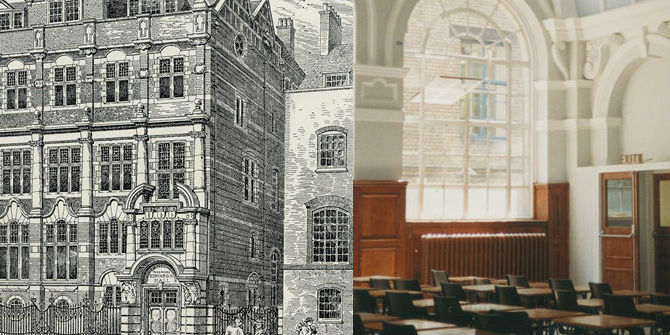

Walking past the LSE Library today, you would never guess that this site once hosted one of London’s most notorious burial grounds. Mhairi Gowans explores the history of what was once known as the Green Ground and how it came to be synonymous with disease and corruption.

We are sorry to state that we shall exhibit such a narrative of appalling scenes, from official and authentic sources as will ‘make the hair stand on end’

– Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 7 August 1842

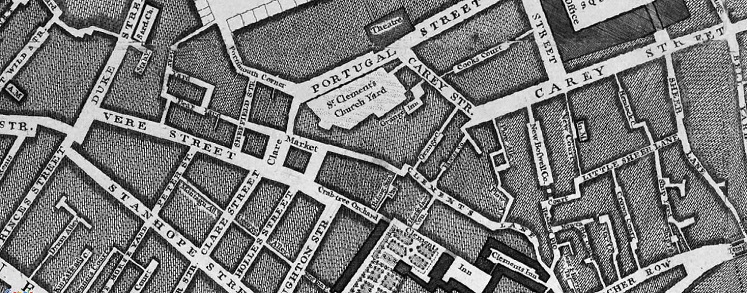

As the London population swelled, from roughly a million people in 1800 to 6.9 million by the end of the century, there was extraordinary pressure on the city’s burial grounds. This was particularly the case in Clare Market, which had become one of London’s worst slums – a rabbit warren of streets, alleys and dilapidated buildings supporting a population of 6,000 people. The parish burial ground, known colloquially as the Green Ground, was on the corner of Clare Market and Portugal Street and had been bought by St Clement Danes Church in 1638 when the Clare Market area was first being developed. By the 19th century, however, it could not take the number of people who needed burial.

The soil of this ground is saturated, absolutely saturated, with human putrescence

– George A Walker, Gatherings from Grave Yards 1839

What happened in 19th century London when a graveyard became overcrowded? Henry Stanton, a resident of 40 Clements Lane, wrote a statement to the House of Commons in 1842 on the Green Ground. He described seeing a gravedigger digging a hole and removing what looked like a relatively new coffin before bringing up body parts. The body of Stanton’s daughter lay in the Green Ground, causing him great distress as he feared witnessing the gravediggers removing her decayed body.

Stanton’s story was corroborated by a whistleblowing gravedigger called John Eyles, who gave his testimony to a government committee that same year. Eyles described how he had dug up coffins and bodies on the orders of the sexton, including details on how he had learned to avoid the gas or “soup” that came out of lead-lined coffins once they had been broken into. Eyles also testified to seeing his own father being dug up by fellow gravediggers.

I saw them chopping the head of his coffin away. I should not have known it if I had not seen the head with the teeth. One tooth was knocked out, and the other was splintered. I knew it was my father’s head, and I told them to stop, and they laughed.

– John Eyles, Planet, 28 August 1842

Another concern was the state of the Clements Lane almshouses where the paupers were buried. In the words of another gravedigger, William Chamberlain, it was in a state of “complete putrefaction,” with bodies buried only one foot below the surface. The Evening Star claimed this graveyard was so full that a summer shower would be enough to un-bare the coffins. A further site of scandal was the St Clement Danes Vestry, situated where our St Clement’s building is today. Its “dust-hole” was described as “stuffed” with coffins, with all the ones on the bottom laying in water.

It is then a fact that the sexton is interested in the burying of as many bodies as possible in the churchyard?

– Report from the Select Committee on Improvement of the Health of Towns, 1842

Why did the sexton order such inhumane practices? William Chamberlain testified to a government select committee that the sexton received a fee for every person buried. Consequently, Chamberlain said, “the more bodies he can bury, the more it is to his profit.” This gravedigger also described how the sexton would inter and receive the fee for the burial of stillborn babies but would not record these burials in the books to cover up the state of overcrowding. The practice was so lucrative that Edwin Chadwick’s supplementary report into city burials found that one clergyman was earning £892 7 shillings and 8 pence a year from burials – the equivalent of £129,000 a year today.

Unsurprisingly, the people of Clare Market suffered terrible ill health. Clements Lane resident John Irwin reported that he and his wife had become unwell since moving there and that many of their lodgers had died of typhus, with one couple dying only 3-4 months after moving in. John Irwin described the burial process for one deceased lodger, a man called Mr Britt. Britt lay dead for 12 days in Irwin’s house before being buried in the Green Ground – within ten feet of Irwin’s wall. Mr Britt’s grave was then opened a mere two weeks later for a new burial.

I saw the grave opened a fortnight afterwards; I considered with myself what an abominable shame this is to open the grave and bury another so soon after.

– John Irwin, Planet, 28 August 1842

In conducting his supplementary report for the government, Edwin Chadwick came across a Clare Market slaughterman who had a hobby of keeping birds. Between the slaughterhouse, the tripe factory and the Portugal Street burial ground, this man believed that the air quality of the area was causing his birds to die. George Walker, a Drury Lane surgeon who made the public health fiasco around graveyards his crusade, recorded a story of visiting a man ill with typhoid on Clements Lane in his 1839 book Gatherings from Grave Yards. Walker describes a man with broken health whose window looked out onto the sight of an open grave in the Green Ground. The man explained to Walker that the grave was for the man who died in the room above – “They have kept him twelve days, and now they are going to put him under my nose, by warning of me.”

The ground has been my destruction and my ruin, through the stench, and the dampness, and the work I have undergone.

– William Chamberlain, Report from the Select Committee on Improvement of the Health of Towns, 1842

While much of the public outcry around the London burial sites occurred during the 1840s, the government did little to act until a terrible outbreak of cholera occurred in 1848, killing 60,000 people. While the cholera outbreak was due to contaminated water, probably due to the policy of letting the city’s sewers out into the Thames, the outbreak led to the Burial Act of 1852. This act banned inner city burials, causing the closure of 226 burials sites across London. The bodies in the Green Ground on Portugal were dis-interred and relocated to the new municipal cemeteries with the now vacant land being used for an extension of the neighbouring Kings College Hospital.

Newspaper quotes were sourced using the British Newspaper Archive

Images:

John Roque’s map from Museum of London Archaeology

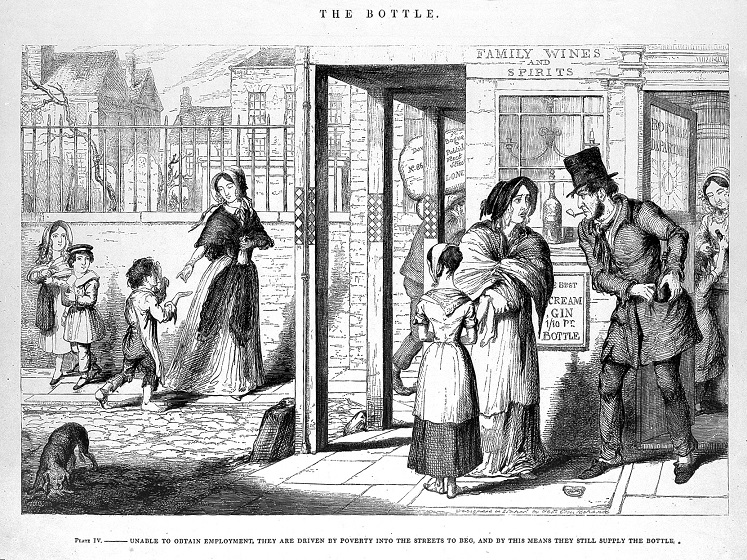

The bottle from the Wellcome Collection

Fantastic informstion here thank you ! My ancestors lived in this area in the 1780s and 1840s and it has helped with my research into the streets they trod and the lives they led .

Really illuminating and Im so grateful for building up a picture of the area thanks once again

Fascinating article – love the history that lurks beneath LSE! Caroline Arnold’s Necropolis: London and Its Dead covers the history of graveyards in London and includes those around the St Clement Danes and Clare Market areas. It’s brilliant and grisly read.

Compelling read! It gave a really vivid picture and a glimpse into living conditions in the area around the period.

Fantastic article Mhairi. I’ve read this on Halloween and it’s given me goosebumps! Appalling to hear how the poor of the day were treated. The profiteers off of the dead and the government of the day were the real ghouls!