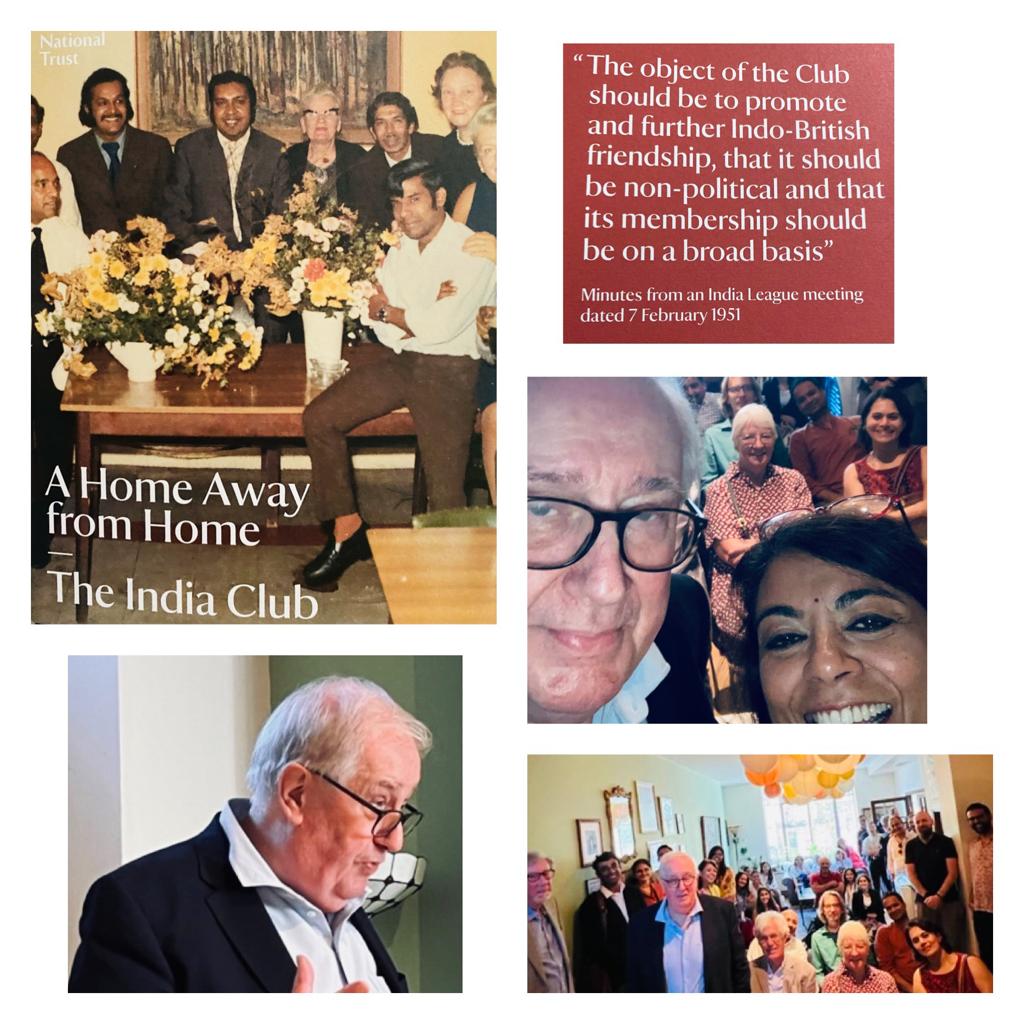

The India Club in London opened in 1951 and closed its doors in 2023. More than just a restaurant “up the stairs” on The Strand, it was a meeting place which holds a very special place in the history of London and for the Indian community in London. But it was much more besides, writes Professor Michael Cox, who explores the roots of the Club in the Indian independence movement and its connection to LSE.

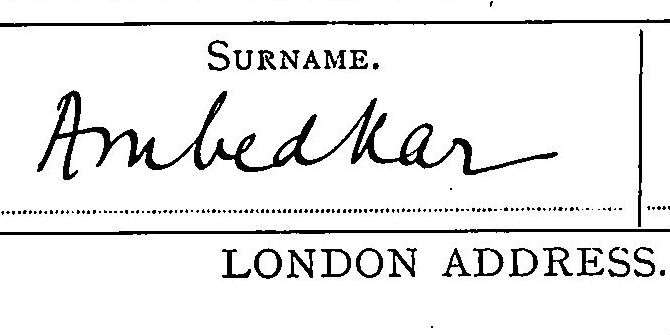

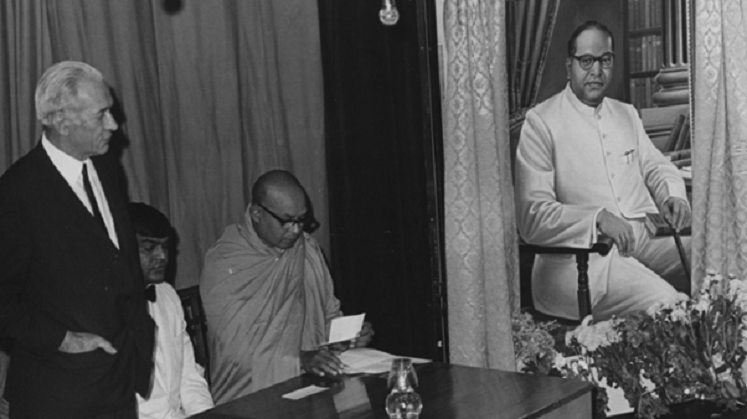

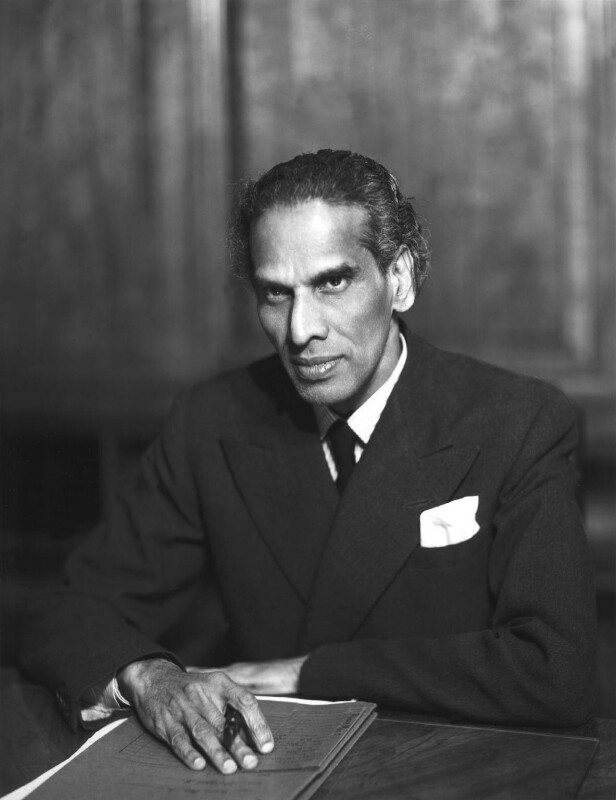

The India Club was, as the name says, a “Club” (until 2008) which can trace its roots back to the India League, a historic organisation which played a prominent role in the Indian independence movement. Founded in 1928, one of its principal movers of the India League – probably its most important – was Krishna Menon, who in 1947 was appointed the first High Commissioner for India to Great Britain. Menon also had a hand in setting up the India Club in 1951 to serve the purpose of providing a meeting place for the Indian diaspora. Indeed, a Free Legal Advice Bureau was created at the Club. The venue was also used as an events space by the Indian Journalists’ Association, the Indian Workers’ Association and the Indian Socialist Group of Britain.

But it aimed to do something else besides: to maintain close and cordial relations between those in Britain who had supported Indian independence and the Indian community in London. This was certainly something Menon sought to encourage. It was once said that Menon had an “ambivalent attitude” to Britain. He opposed its presence in India but valued British freedoms or what might loosely be called the “British way of life” with its liberal values of free speech, free press and free assembly. Significantly, Menon supported India’s membership of the Commonwealth.

For this perhaps we have to thank many people no doubt, including of course Menon himself. But there was perhaps one man with whom Menon was close throughout his time in London after 1929: Harold Laski, who joined LSE in 1920. Laski had always been a radical. But he became a convert to the cause of Indian independence when he was appointed a juror in a 1925 court case involving General Dwyer and his role in the Amritsar massacre. Laski came away disgusted at the bias of the judge and his fellow jurors and the racism on display. It was at this point, according to Menon, that Laski “became one of us”. But becoming “one of us” did not make Laski especially popular amongst many of his fellow “Brits” who thought the British Empire a most perfect instrument for the advancement of “civilization”. But as Gandhi – who got to know Laski – once quipped when asked what did he think of “western civilization”: “it would be a good idea”.

Menon meanwhile had become a student of Laski’s at LSE in 1925, graduating with a first class degree in 1927. But he was not just a student and admirer of Laski’s. They worked closely together politically. They also developed a close personal friendship. As Laski’s biographers rather nicely put it, Menon became a constant presence in the Laski household. If the phone rang at 9am it was more often than not Krishna Menon.

But this not untypical. Laski worked extraordinarily hard to support all his students, but perhaps especially those from British India who studied at LSE in large numbers. As one of them said:

It was my first time abroad. But Professor Laski put me at my ease and gave me the feeling that my views on the affairs of the day were of the utmost importance… there was no condescension; differences of opinion were respected; We soon understood each other deeply and affectionately.

But Laski in turn worked indefatigably for Indian independence. He was tireless. As he noted in 1949, a year before he died:

I do not know how many times I have gone to meetings that I did not want to attend, have made speeches I did not want to make, have written articles that I did not have time to write. Why? Because I was under the grim control of this irrepressible embodiment of the will of India to be free and I look back and what I owe Krishna Menon for having made me attend as a member of his army.

The great sadness is that Laski died in March 1950, a year before the Club was established. I am sure he would have been very proud of what it went on to achieve over the years. He would also, I’m sure, be deeply saddened to see this vital piece of history of a very special relationship coming to an end.

To find out about LSE’s South Asia collections head to the LSE Library’s Traces of South Asia webpage.