It may surprise you that the notorious Green Ground graveyard on Portugal Street was not the only burial site on LSE’s campus, writes Mhairi Gowans. Situated where our Centre Building is today, Enon Chapel became infamous in Victorian London for its scandalous burial conditions.

During the 19th century, the Clare Market area had become a densely populated slum in which tightly packed streets were closely neighboured by four overpopulated burial sites. As the public health campaigner George Walker said, “The living here breathe on all sides an atmosphere impregnated by the odour of the dead.” One of these overcrowded burial sites was Enon Chapel, a place of worship once situated amongst the network of buildings that crowded the border of Clare Market and Clement’s Inn passage. Entered via a “narrow, dingy court,” it opened as a Baptist chapel in 1823 under the jurisdiction of the minister, a man called Mr Howse.

It is one of the most filthy places which can be found anywhere; here is Enon burying ground on one side, and this in Portugal Street on the other, and the stinking market in the centre.

– William Burns, A Supplementary Report on the Results of an Enquiry into the Practice of Internment in Towns, 1842

By the 1840s, the name Enon Chapel was infamous as one of the worst of London’s graveyard scandals. As we saw in our investigation into the Green Ground, there was money to be made in burials, and Mr Howse ensured he made it by offering cheaper burials than the neighbouring parish church of St Clement Danes. An adult burial with St Clement Danes would cost £1 17 shillings and two pence, but at Enon Chapel, it cost only 15 shillings. This was attractive to the highly impoverished people of Clare Market, and consequently, the Chapel did a brisk trade in burials, with one witness claiming that the Chapel could bury nine or ten people in a day.

And from the stench that arose from the dead bodies the congregation in a great measure left the chapel; and the remark which was made was, that more money was made from the dead than the living.

– George Whittaker, Undertaker, Report from the Select Committee on Improvement of the Health of Towns, 1842

But where was the Chapel interring the deceased? Unlike the parish church, it had no graveyard, so the coffins were placed in the vault beneath the chapel in a space just 59 feet by 29 feet. According to one ex-congregant, Samuel Pitts, an estimated 12,000 people had been interred into this small space over two decades. As the vault became increasingly cramped, it was then believed that coffins were broken down and used by the minister and his family for firewood. There were also rumours that the bodies were thrown through an opening into the sewer that ran beneath. One witness for the 1842 report on the health of towns claimed that he had been employed to remove “rubbish” from the vault following work to enlarge the sewer below. This rubbish he then tipped near Waterloo Bridge, where they were making a pathway, though on one occasion, he testified handing over rubbish to workmen on Clement’s Lane.

There were some men repairing Clement’s Lane; they asked me to give them a few baskets of rubbish, which I did, and they picked up a human hand, and were looking at it.

William Burn, Report from the Select Committee on Improvement of the Health of Towns, 1842

The Baptist community naturally did not like the reputation that Enon Chapel was bringing to their faith. As the Baptist newspaper the Patriot pointed out, if the witness statements were true, Mr Howse must have been “one of the foulest, vilest miscreants that ever disgraced humanity.” They question how congregant Samuel Pitts could know of the burial practices and still attend the chapel. They also report that Howse’s wife denied the allegations and that the chapel’s records show only 3,503 burials – which would only amount to nine people a week, far below the numbers quoted by the witnesses.

Regardless of whether the number of 12,000 was inflated, Enon Chapel was a scandal. All that separated the vault from the congregation above were thin wooden boards. None of the coffins were lead-lined, so gasses and smells spread easily upstairs. Indeed, there were reports of people fainting during services and of black bugs, nicknamed body bugs by the Chapel’s Sunday School children, infesting the building. Public health campaigner and local surgeon George Walker described the vault in his 1839 book, Gatherings From Grave Yards.

I have several times visited this Golgotha. I was struck with the total disregard for decency exhibited – numbers of coffins were piled in confusion – large quantities of bones were mixed with the earth.

– George A Walker, Gatherings from Grave Yards 1839

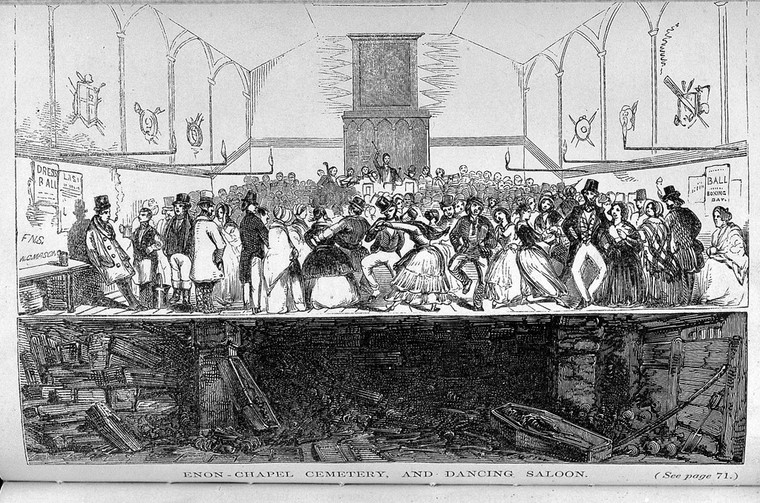

At the time of the 1842 investigations into inner-city burial, Enon Chapel had ceased to be a place of worship due to the death of Mr Howse. Instead, the Irish Temperance Society rented the building to host meetings and dances, but the vault remained piled high with coffins. Reports from the time claim that the dances were advertised as “Dancing on the Dead”, with the cost of the experience standing at three pence.

Disapproving of this state of affairs, George Walker took over the building so that he could remove the bodies to Norwood Cemetery. However, before he did that, he opened the Chapel’s vault so the public could witness the total depravity of what lay there. On arrival, in a small room near the entrance, the body of Mr Howse himself was on display – and he was reportedly recognised by those who knew him by his “screw foot”. From there, the public could enter the upper hall where the bones, coffins and bodies lay, waiting to be removed to Norwood. Some of the bodies were open to the elements, their decomposed corpses on display for public view, including the bodies of children and infants.

There are children’s legs shrunken by terrible deformities, while the little socks into which they were placed for the last time, probably by tender hands, are only discoloured.

– The Era, Sunday 5 March 1848

Why did a man, supposedly disgusted by the disrespect of the dance hall above the charnel house, exhibit these remains? It could be that Walker saw the public circus, and consequential public outrage, as a way to achieve the banning of inner-city burial. Walker and the Victorian scientific establishment were still operating on the idea that disease was caused by bad smells called miasmas and so, for those mid-century public health authorities and campaigners, their focus was on the eradication of bad smells from people’s living conditions.

George Walker ultimately succeeded in his campaign, with inner-city burials being banned by the 1852 burial act. When George Walker died in 1884, it was for his work on graveyards that he was remembered for in the press. While numerous people and groups helped bring about burial and sanitation reform in the mid-19th century, it is clear from this poem in the Hampshire Post and Southsea Observer that it was seen in the public eye as primarily Walker’s achievement.

Who closed the intramural tombs?

Asks many a writer, many a talker,

“I shut them up!” Lord Shaftesbury fumes,

The very Graves replying – WALKER!

Who gave pure air unto a host?

Who of plugged chinks was the uncaulker?

“Why I!” shrieks Southwood Smith’s pale ghost,

The very Air echoing – WALKER!

But when – “Both good deeds, I did – there”

roars Chadwick, like some brazen hawker,

Then – like the Graves and like the Air

The very London Boys cry – WALKER!

– Hampshire Post and Southsea Observer, Friday 11 July 1884