Tanya Harmer and Gloria Miqueles first had the idea of an exhibition to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup in the summer of 2022 over coffee in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Over the next year, the idea took on a life of its own. Their research in LSE’s archives and library collections and the Documenting Chile Archive at the University of East London’s Living Refugee Archive revealed Chilean refugees’ experiences coming to Britain as well as the enormity, creativity and breadth of the British solidarity movement that developed after 1973.

From campaigning against repression and human rights violations to welcoming refugees, people around Britain, including at LSE, worked tirelessly to promote a more just, democratic society in this country and in Chile. Chilean refugees were central to the struggle for rights and resistance against the dictatorship, at while simultaneously navigating a new life in Britain. Here, Tanya and Gloria reflect on some of the highlights of the exhibition, Resistance, Rights and Refuge: Britain and Chile 50 years after the Chilean coup.

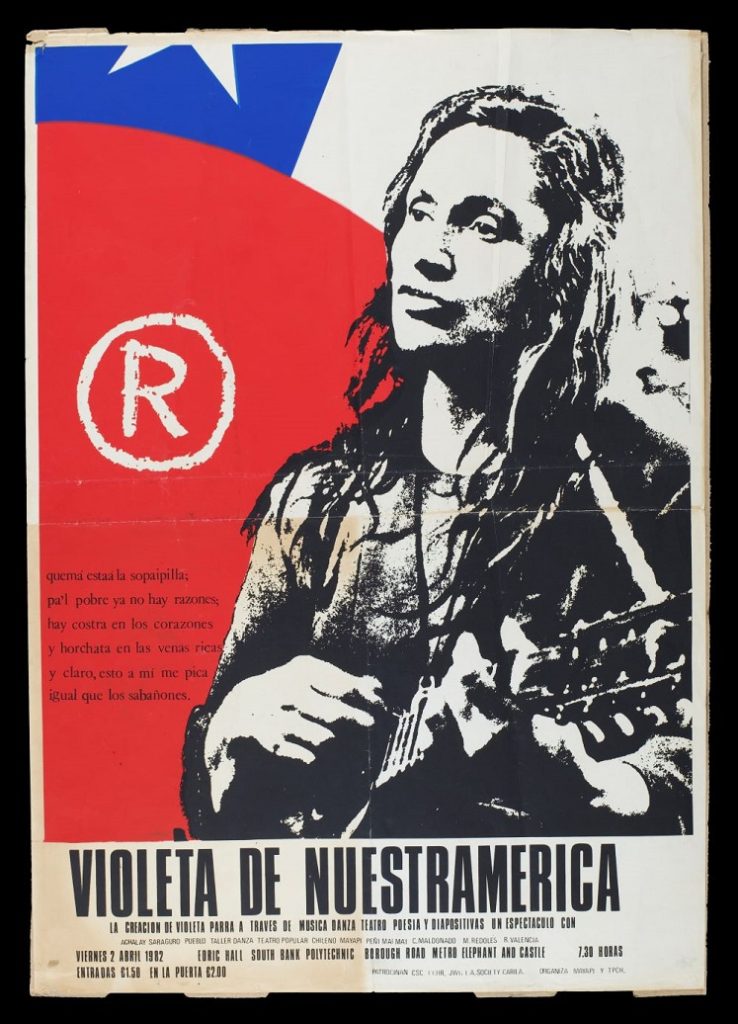

1. Violeta de Nuestra America (2 April, 1982), Living Refugee Archive

This poster, featuring Violeta Parra, one of the founders of the Nueva Canción movement struck us as historic and significant the minute we saw it. The R on the red of the Chilean flag in the background was a symbol of Resistance during the dictatorship and was painted on walls in Chile during the time. Violeta’s guitar and the poster itself, inviting people to attend a cultural evening of Chilean music, theatre and poetry at South Bank Polytecnic University, speaks to the power of cultural resistance to the dictatorship. At the bottom of the poster, you can see the entrance fees (£2) to raise money for the solidarity campaign as well as a list of those involved, including the artists performing, such as the folk group, Mayapi, and the principal solidarity organisations in Britain sponsoring the event – the Chile Solidarity Committee (CSC), the Chile Committee for Human Rights (CCHR), the Joint Working Group for Refugees from Chile (JWG), CARILA (a cultural committee for Chile) and the Latin American Society at London’s South Bank University. – TH

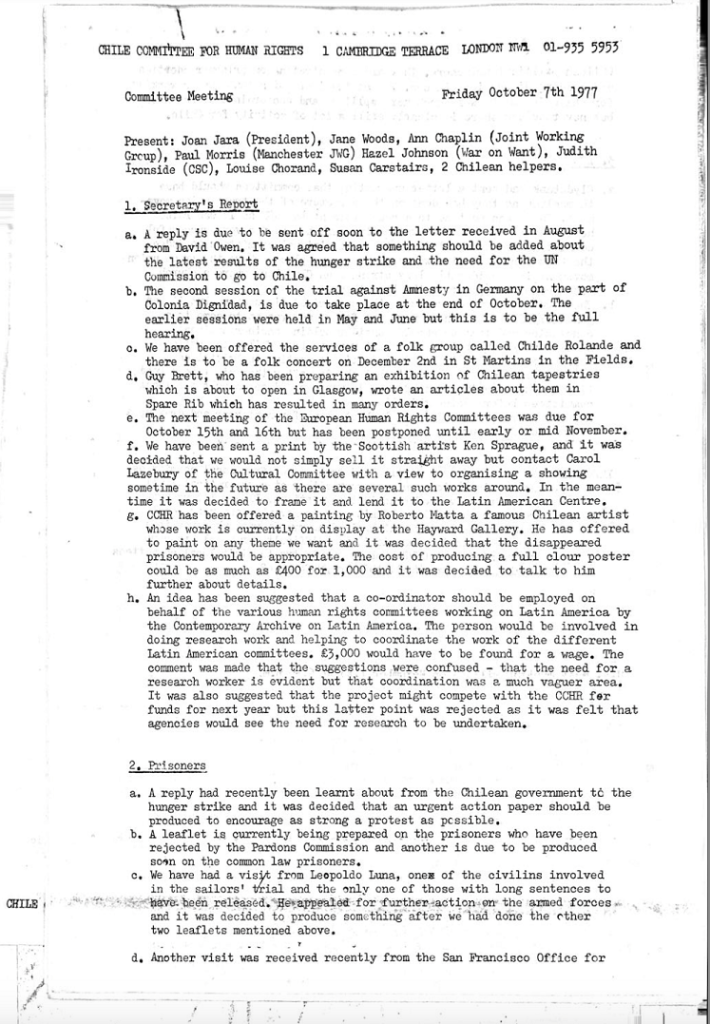

2. CCHR, “Minutes,” October 1977 – UNA/28/2/8

These minutes, found within the United Nations Association records in LSE’s archives, record a meeting of the Chile Committee for Human Rights (CCHR) in October 1977. They reveal the extensive networks that the CCHR, founded in Britain in 1974 to campaign for human rights in the context of brutal repression in Chile, had with international governmental and non-governmental organisations like Amnesty International, the United Nations and the European Human Rights Committees. It also reveals the variety of strategies CCHR used to raise awareness of what was happening in Chile and to raise funds, from concerts, to art, to articles about arpilleras in the feminist publication, Spare Rib, to lobbying government ministers and producing information leaflets recording abuse. As with other items in the exhibition, the minutes reveal the tireless work that went into recording abuse and visibilising what was happening in Chile. This work, as the exhibition notes, contributed to the global human rights revolution of the 1970s. – TH

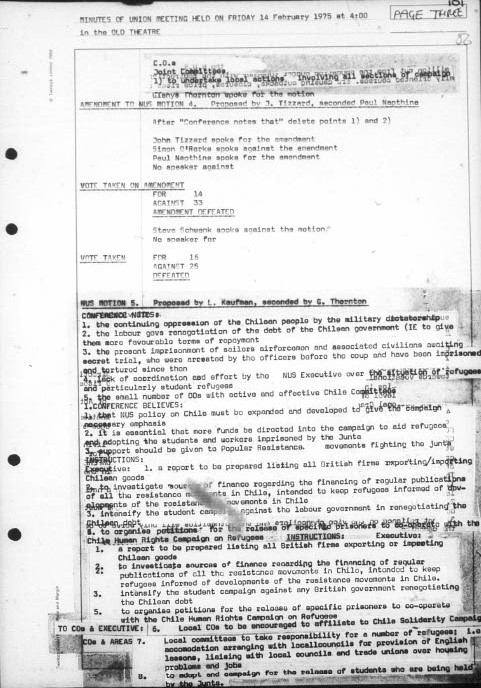

3. LSE Students’ Union, “NUS Motion No.5,” 14 February 1975 – COLL MISC 0649/6/3

Once I saw how much coverage of Chile there was in The Beaver, I knew that it was likely to have also come up in LSE Students’ Union Debates and Meetings. Although originals, like the one displayed in our exhibition, are housed in the LSE Archives, the minutes of union meetings have all been microfilmed to preserve them. So, to find references on Chile involves scrolling through reams of records of lively exchanges and debates at the LSESU in the wonderful reading room of The Women’s Library. As well as resolutions to condemn the coup in 1973, these minutes of a meeting in the Old Theatre on 14 February 1975, caught my eye. They record an National Union of Students (NUS) Conference resolution to expand and develop solidarity with Chile, including raising funds to aid refugees arriving in Britain and organising committees to find housing, jobs and English lessons for them. Despite current government rhetoric, it is important to remember solidarity for refugees has historically been important to British people and students who have fought for refugees’ rights and continue to do so. – TH

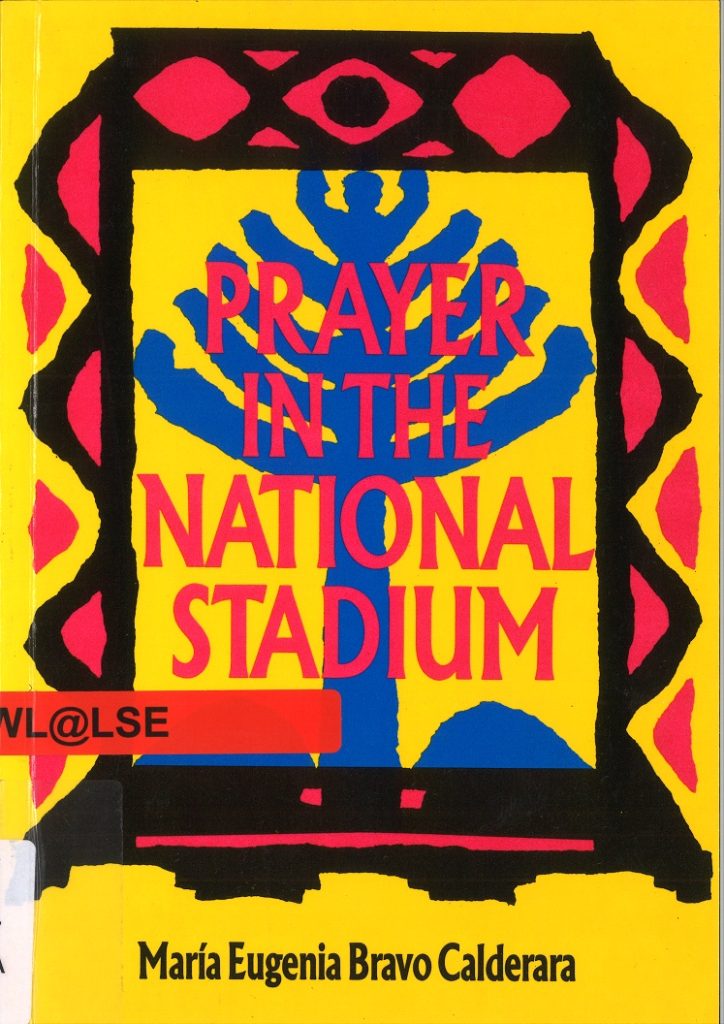

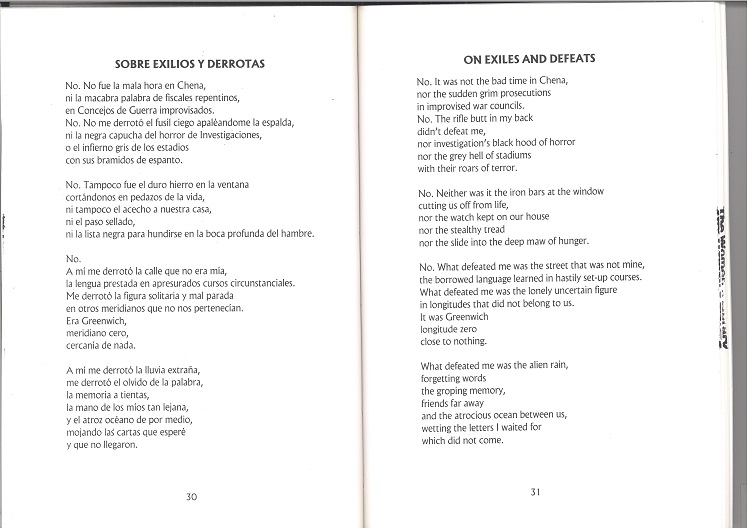

4. Maria Eugenia Bravo, Prayer at The National Stadium, Katabasis, 1992 – TWL@LSE Books – “On Exiles and Defeats” available online at resistancerightsandrefuge.uk/chileansinbritain

“On Exiles and Defeats,” is a poem by Maria Eugenia Bravo Calderara from her book Prayer in the National Stadium. In Part 2 of the book, there are a number of poems about her experiences as an exile in England. All of them are so relatable to all of us Chilean exiles, but “On Exiles and Defeats” caught my attention. The poem is poignant to me in its analysis of what has had the greatest impact on her life what one could call: “defeat by exile”. I think that all Chileans at some point in our exiled lives have felt this defeat. It is a poem that should be mandatory in schools, universities and other public settings, especially in today’s Chile where an increasing denialism is reviving the “Golden exile” narrative, a false image of exiles created by the Pinochet regime that ignored the traumatic impact of exile on Chileans. – GM

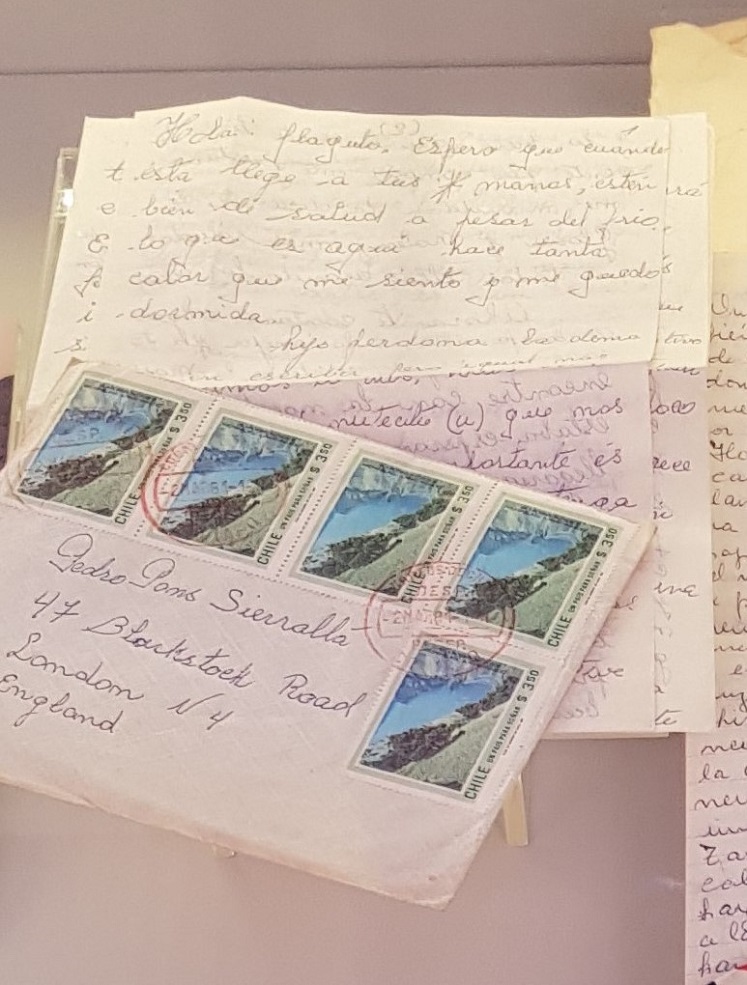

5. Letters & envelopes between exiles and their families in Chile – Nelsa Silva and Paty Pons Private Collections

The content of Pedro’s letter in the exhibition from his mum is all too familiar to Chileans who have experienced exile. It includes wishes, concerns and daily-life accounts common to all letters shared between family members of all walks of life: “I hope that when this letter reaches you, you will be well, despite the cold weather.” The letters reminded me that, for those of us who fled to the UK, staying connected with our loved ones in Chile was difficult. When Chileans started coming to the UK in the 1970s, the only means of communication with family was by post. During those years, before easy phone communication and social media, letters were a lifeline for Chileans. They helped us to shorten the distance which the civic-military dictatorship forced between us, in this new, cold and distant land, and our loved ones in Chile. – GM

6. Photograph of Sara De Witt leaving Chile, Private Collection

This photo in the exhibition conjures for Chilean refugees the moment when they had to flee the country for a life of exile, some alone, others with extended family, many never to return. The photo shows Sara trying to smile to her family as she says goodbye from the airport terrace, attempting to comfort them by hiding her sadness at having to leave behind her country, life and family. Enforced exile was central to Pinochet dictatorship’s strategy for consolidating and retaining control of Chile for his 17 years in power. He never thought that these exiles would immediately start organising to wage political resistance to his dictatorship. – GM

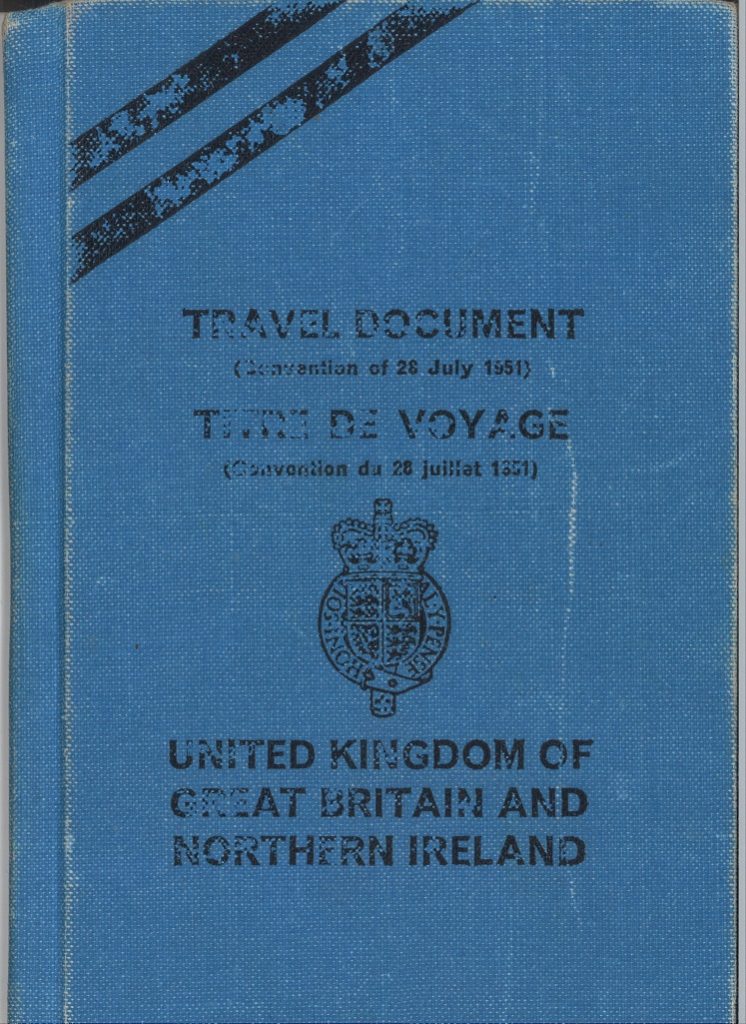

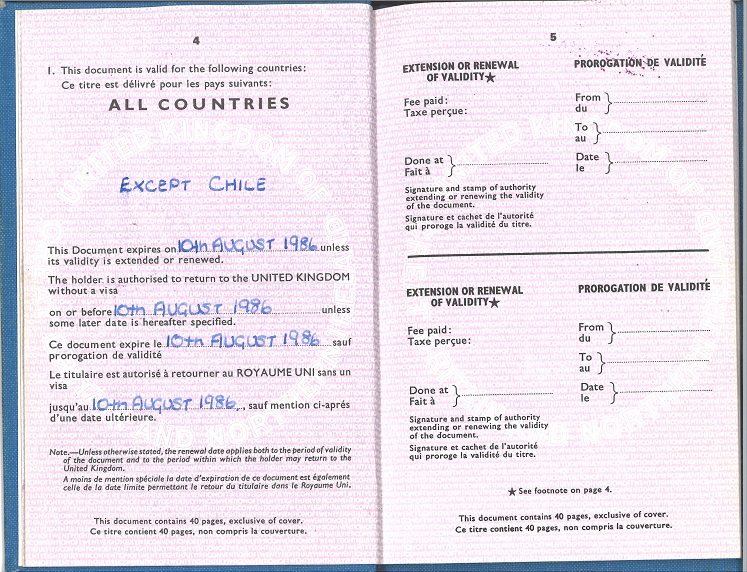

7. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, “Travel Document” – Private Collection

Chileans fleeing the country arrived in the UK with a “Letter of consent” provided by the British Embassy in Chile. Once granted a declaration of refugee status, Chileans were able to get a refugee travel document, like the one in the exhibition that resembles a blue passport. This Home Office travel document is sometimes referred to as a 1951 Convention Travel Document or Geneva Passport, which allowed Chilean refugees to travel outside the UK and come back. Although getting this document was an important event for us, it brought with it the sad realisation that the “Except Chile” restriction meant we were expressly forbidden from returning home, which made separation from home more painful and harsh. – GM

This post originally appeared on the LSE Review of Books

Note: This post gives the views of the authors, and not the position of LSE Review of Books or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Images are provided courtesy of LSE Library/London School of Economics and should not be reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder.