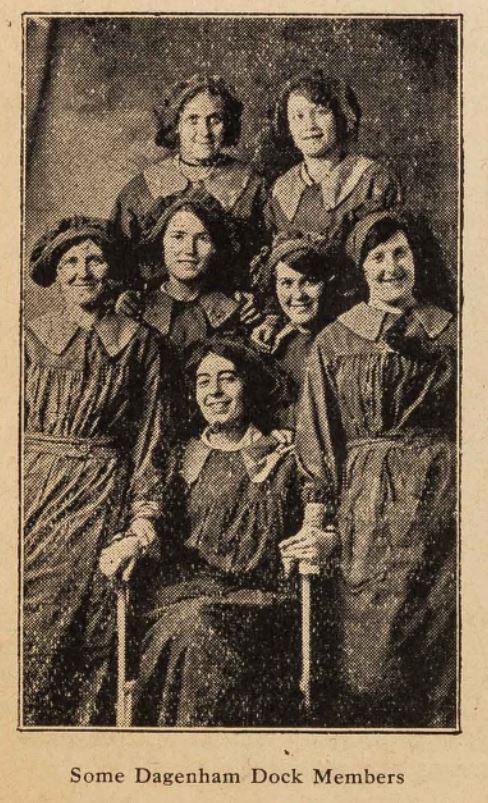

This Women’s History Month we are delving into the world of women’s work, exploring the jobs, industries and conditions in which women have worked by using materials from The Women’s Library at LSE, writes Mhairi Gowans. In our third blog we explore the life of female munitions workers who were key to the war effort in both the First and Second World Wars.

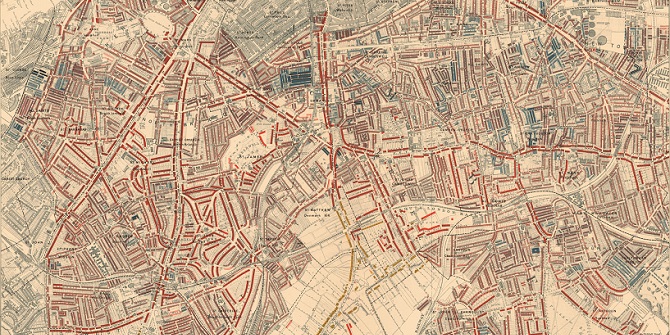

When the Industrial Revolution happened, the number of women working outside the home increased. By the late Victorian period factories were a common source of employment for working class women but pay and health and safety conditions were poor. When World War One required men to fight, employment opportunities for women improved, particularly in industries supporting the war effort, such as munitions. By the end of the war, over 700,000 women were working in munitions.

The women’s rights newsletter, The Woman Worker, sought to improve conditions for women workers through trade unionism. The 1916 editions in the LSE Digital Library report on the plight of munitions workers in different parts of the country. In August 1916 it tells the story of a group of Darlington women who had been promised £1 and 28 shillings per week at a munitions factory in Barrow. However, on arrival the women found that the realities of job meant they could only expect to earn around 14 shillings.

This was not good enough for the Darlington girls who wanted to live in decent lodgings.

– The Woman Worker, August 1916

In response to pressure from the National Federation of Women Workers, the manager of the factory promised to source and pay for good quality lodgings but that he would not improve pay. Ultimately the women workers, with help from the Federation, arranged for the factory to pay for their return home to Darlington.

In the same issue, the conditions for women working for Nobels Explosives in Llanelly, Wales was featured. The women were receiving a rate of seven and a half pence for their work while the men were receiving nine and demanding 10. When the factory’s head office ignored the women’s demands for equal pay, a strike took place resulting in the case being brought before the Munitions Tribunal.

The girls all say they can do as much or more than the men can do, and they ought to have the same rate.

– The Woman Worker, 1916

Working in munitions meant that these women were doing extremely dangerous work. Prolonged contact with TNT resulted in workers developing yellowed skin and hair, with some women even giving birth to yellow babies. However, the worst dangers came from explosions. One woman working in Risley during the Second World War recounted an experience while carrying a box through the factory.

There was a massive explosion from an adjoining room. In shock I dropped the box. I was horrified to see a young woman thrown through a window with her stomach hanging out. I was sickened. Luckily, for some reason the box, containing detonators, did not explode. Or we’d have had our legs blown off.

– Mabel Dutton, Bomb Girls, 2014

Despite the danger those working with explosives faced, munitions workers were not officially recognised by the government for their contribution during the world wars until 2012 when war-time munitions workers were allowed to participate in the Armistice Parade for the first time. Munitions workers can now apply for a veterans badge using the government’s website.

Explore the archives of The Woman Worker through LSE’s Digital Library.