Former US President Bill Clinton has spoken at the London School of Economics and Political Science twice, in 2001 and 2012. The main focus of both talks was the current age of global interdependence and the need to realise and capitalise on our common humanity.

In the LSE event recording archives you can find audio and video of Clinton’s 13 December 2001 talk, introduced by LSE academic Meghnad Desai and chaired by LSE Director Anthony Giddens.

In the wake of 9/11, President Clinton asked the audience at LSE, which do you believe is more important: our differences or our common humanity? Looking back on his own presidency (1993-2001) Clinton spoke about his vision for the future in the context of the post-9/11 world and the fight against terror, taking in war in Afghanistan, the global economy and the AIDs epidemic.

These photographs are from the event:

In his introduction, Professor Giddens welcomes President Clinton and states that this is in fact a return to LSE, since he had first visited in the late 1960s while he was a student at Oxford. Giddens and Clinton had first met during US-UK policy talks with the Blair and Clinton administrations in 1998, which he believes established an framework for progressive politics, influential on the UK’s Labour government and in Europe. Giddens reflects on the Clinton administration as a time of economic growth, low inflation and high employment – and economic inequality was revered by Clinton’s policies. Giddens invites Lord Meghnad Desai, as LSE’s own “Don King”, to introduce the lecture.

Lord Desai introduces Clinton to speak about globalisation, referencing LSE’s Centre for Global Governance, established in 1991, which aims to influence policy. The event has been made possible by the LSE Global Dimensions programme, supported by BP. He goes on to speak about Clinton, as the only Democrat to have been re-elected since the Second World War, and also the only left-handed one in the entire 20th century! According to Desai, Clinton’s two career mistakes were: going to Oxford rather than LSE – and compounding the mistake by sending his daughter to Oxford too.

Speaking through a cold, President Clinton thanks the room for forgiving him his two mistakes. He confirms that while he had visited LSE as a student, “I never came here for anything remotely approaching an academic purpose… perhaps I will remedy that somewhat tonight.” He goes on to thank Giddens for his work on the Third Way movement, and making Blair and Clinton “look good”. His talk will follow the theme of that work, “to move beyond the false choices of the past and look at our world and our future possibilities in entirely new ways.”

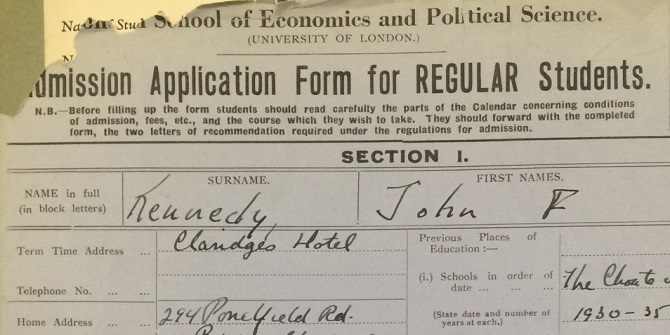

He says that LSE has a “mythic” place in the imagination. President Kennedy spent the summer of 1935 here, at the time of the LSE-Cambridge debates between Hayek and Keynes, that changed the way people looked at the world. Another former student, Mick Jagger changed the world in his own way, ignoring the advice of a teacher who said there was no money in music.

“For a long time the world has turned to LSE for some understanding of each new age.” Clinton credits LSE’s founders, in particular Beatrice and Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw with the introduction of the idea that governments had an obligation to improve the lives of their citizens. Moving to period after the Treaty of Versailles, LSE’s Lord Attlee, Harold Laski and Vera Anstey laid the intellectual groundwork for social reforms that we now take for granted – like old age pensions and national health. He summarises a respect for LSE’s involvement in rebuilding on the world stage after other key events of the 20th century, post Second World War and Berlin Wall.

Clinton’s presidency coincided with the end of the Cold War and a new age of global interdependence, “more sweeping and profound than anything the world has ever known before. Changing the way we work, the way we live, and the way we relate to each other and the larger world. ”

The Third Way

“I tried too to change the way people think about politics. And to develop a political philosophy relevant to the new century but rooted in enduring values. Opportunity for all. Responsibility from all. A community of all citizens who accept certain basic rules of the game. Everyone counts. Everyone has a role to play. We all do better when we help each other.

“Because the world has gown increasingly interdependent, and isolation is no longer an option, we need a politics of unity. A politics that integrates what we feel, what we believe, and what we experience.

“And those of us like Professor Giddens and me, and Prime Minister Blair, believe that required us to move beyond the old dividing blocks of industrial aero-politics.

“Then we had to find an economic policy that instead of being pro-Labour or pro-business, actually helped them both.

“And then we had to find social policies that instead of just helping the poor or only helping the middle class, helped both.

“Then instead of making choices that would protect the environment but hurt the economy, we had to find a way to advance both.

“Then in a world in which most men and most women, most parents, are in the workforce, we had to find a way to help citizens to avoid choosing between being effective workers and effective parents. We had to advance simultaneously the cause of work and family. And I could go on and on and on.

“But this required us to rethink the role of government. And to conclude that the primary business of government was to establish the conditions, and give people the tools, at home and around the world, to make the most of their own lives.

“This whole idea, some people derided as trying to have it both ways. As having no convictions. As having no content. As straddling the middle of the road. But it’s rather hard to quarrel with the results that the implementation of these ideas achieved, in the United States, in the UK, and elsewhere where they have been seriously pursued.”

Clinton likens this to the concept of non-zero-sum solutions, from the work of author Robert Wright who argues that as societies become more complex and interwoven, non-zero-sum solutions become more necessary.

“A zero-sum game is a soccer match. An election. In order for someone to win, somebody else has to lose. A non-zero-sum game is a good friendship, a good marriage, a good business partnership, a good peace process.

“In order for victory to accrue to one side, the other side has to feel that it has won as well. So Wright argues that with increasing sophistication and inter-relationships, it will become more and more necessary to find non-zero-sum solutions. That is not a prescription for a static moderation, but for dynamic progress.

“That is in essence what those of us associated with the Third Way movement tried to do … for all of our differences that make life more interesting, our common humanity is more important and we ought to organise our lives around it.

The impact of 9/11

“For everyone who fundamentally agrees with that, it is possible to work together and to make progress and to bridge even quite large differences. But non-zero-sum solutions are not possible when we deal with people who believe our differences are more important than our common humanity.

“That is the simple explanation of September 11th. Where people claim the benefits of technology, open borders, easy access, widespread information and use them to hideous effect. Because they believed our differences were more important than our common humanity. They believed that the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were symbols of American corruption and materialism and abusive power.

“Well, you know I live and work in New York. My wife represents New York in the United States senate. Our daughter Chelsea, who is here with me tonight, was in lower Manhattan on September 11th. That’s not what we see. There were people from over 80 nations killed on September 11th. Including about 250+ from Great Britain. And over 500 Muslims.

“To me those people represent the world that I worked hard for eight years to build. A world of greater freedom and opportunity, a world of greater citizen responsibility. Of both growing diversity and deeper bonds of community. Those who killed them just saw them as legitimate targets. Because they thought their differences were more important than our common humanity.”

“I believe the clash between these views will essentially shape the soul of this new century. Obviously I believe that the vision I share will prevail. But for it to do so, four things must happen.

The fight against terrorism

The purpose of terrorism is not military victory, it is to terrorise. To effect a change in people’s behaviour: afraid of today, afraid of tomorrow, afraid of each other. So they can’t win unless the targets give them permission.

“First we have to win the fight we’re in against terrorism. Second, we have to build a world with more partners and fewer terrorists. That requires us to spread the benefits and shrink the burdens of the 21st century world. Something the wealthy countries have to do.” [He places his hands on his chest.]

“Third, the poor countries have to make some changes, perhaps especially in the Muslim world, to make progress more possible.

“And finally, we will all have to develop a far higher level of consciousness about the correct nature of our responsibilities to each other and our relationships than anything we saw in the century from which we’ve just departed.

“Let me take each of these briefly in turn.

“First, we will win the fight we’re in. It won’t be easy, and I can’t say there won’t be any attacks within Great Britain or again in the United States. But we will win it. Why do I think that? Well, terror has a long history. No region of the world has been spared it. Few people have entirely clean hands.

“In 1095 Pope Urban II urged the Christian soldiers to go on the First Crusade to capture Jerusalem. They did so. When they seized the Temple Mount their first act was to burn a synagogue with 300 Jews. They then proceeded to kill every Muslim woman and child on the Temple Mount. And to leave bitter memories that are still recounted today in the Middle East.

“Throughout the 20th century, people continued to be killed in staggering numbers because of their race, their ethnic origin, their tribe or their religion. Even in the West. And though we Americans have come such a very long way since the dark days when African American slaves or Native Americans could be terrorised or killed with impunity, still to this day we occasionally have someone killed or terrorised because of his or her race or religion or sexual orientation.

“Yet in spite of this long history, no terrorist campaign has ever succeeded. In fact, they usually backfire. Indeed the purpose of terrorism is not military victory, it is to terrorise. To effect a change in people’s behaviour: afraid of today, afraid of tomorrow, afraid of each other. So they can’t win unless the targets give them permission. So far, thank God and all history, nobody has given their permission. I do not believe we are about to be the first to do so.

“However, there is something that makes this particular terrorism more frightening. It is the combination of the perceived vulnerability of powerful and wealthy places with the extraordinary potential of the weapons at hand. So I want to talk about that a minute.

“First of all, it’s important to understand that from the dawn of time, since the first person walked out of a cave with a club in his hand and began to beat people over the head, there was a gap in time until somebody figured out, hey, I can put two sticks together, stretch an animal skin over it, I would have a shield and the club wouldn’t work against me anymore. That is always the history of combat. First the club and then the shield.

“The more lethal the weapons, the more important it is to close the gap in time quickly between the introduction of a new form of offence and an effective defence. Civilisation is still here because so far, even in the nuclear age with mutually assured destruction, we have been able to find the defence in time. There is no reason to believe it will not happen here. But there is a lot to do.

“The modern world is awash in terror. Just since 1995 there have been more than 2,100 attacks. No fewer than 20 in the United States and none, save Oklahoma City, claiming a large number of lives before September 11th. The Europeans, including all of you, have been exposed to terrorist attacks on your own soil for considerably longer. And we Americans have been involved in it at least since 1983, when 240 of our marines and sailors were killed in a suicide attack in Beirut.

“In the years I served as president, we worked very hard to improve our defences and to bring terrorists to justice in the hope a day like September 11th would never come. Law enforcement officials thwarted attempts to blow up the Harlem and Lincoln Tunnels in New York, the Los Angeles airport and planes flying out toward the Philippines. They thwarted an attempt on the Pope’s life. And just over the millennium weekend alone, attempts on the largest hotel in the Mount Jordan, a Christian site in the Holy Land, two large cities in the American north east and north west. They brought a lot of terrorists to justice.

“Good people have been working on this, and our defences have been getting better. But clearly we need to do more. To defend all transportation and critical infrastructure and computer networks. To break into the money networks of terrorism. Something we tried to do that the Congress stopped last year, but just yesterday thank goodness it’s finally decided to give the government the power to do. To track potential terrorists with legal information when they are within our borders. And to secure-this is very important-to secure the world’s rather vast stores of chemical, biological and nuclear materials that could be used to make weapons. There’s a lot to do. But the larger point holds.

“Terror has never worked. We have always managed to close the gap between offensive action and effective defence. We are working hard at it now. We are clearly winning in Afghanistan. Our defences at home will get better. And terror will not prevail. But that brings me to the second point.

“As grateful as I am to Prime Minister Blair and all of our allies for supporting President Bush and this common effort against terror, as sure as I am that they are going to prevail, winning the war in Afghanistan and strengthening our defences at home will not be enough to build the world we want for our children and grandchildren.

“We have built a world without walls. We can’t put them up again. But we’ll force them, all of our children, to live in a world of barbed wire unless we do something to reduce the number of potential terrorists and increase the number of potential partners. We have to begin with the wealthy countries’ obligations to do more to spread the benefits and reduce the burdens of this modern world.

“Think for a moment how you felt on September 10th. If I had asked you then, what is the single driving force of the 21st century world, what would you have answered?

“Well if you’re British or American, you come from some other rich country or you’re upbeat, it seems to me you could have given one of four positive answers.

“You could have said: the global economy, it made us rich and lifted more people out of poverty than ever before in history.

“You could have said the information technology revolution. It’s driving productivity, which lifts growth, and there’s never been anything like it. Believe it or not, when I became president in 1993, there were only 50 sites on the world wide web. 5-0. When I left office eight years later, the number was 350 million and rising.

“Or you might say, that’s very impressive but the advances in the biological sciences will affect more people more positively. One of the happiest days of my presidency was to announce, along with Prime Minister Blair and others, the completion of the sequencing of the human genome. We have already identified the genetic variances that are high predictors of breast cancer. Getting close on Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

“Quite soon, young mothers will bring babies home from the hospital with little gene cards profiling their kid’s future insight: here are the strengths, here are the problems, here’s what you do. And I believe before long babies will come home with life expectancies in excess of 90 years.

“Significant investments in nanotechnology, super micro technology, will give us the diagnostic capacity to see tumours when they’re only a few cells in size, raising the prospect that all cancers will be curable.

“Research is now underway on digital chips to replicate the highly complex nerve movements of damaged spines, raising the prospect that people long-paralysed might get up and walk. This is pretty heavy stuff. And to boot we’ll find out what’s in the black holes in outer space. And we’re still finding new forms of life in the deepest levels of the oceans and rivers.

“Or if like me you’re into politics you could say, that’s all very well but the most important thing is the explosion of democracy. And diversity within democracies. Because that creates the conditions which make all this other progress possible. For the first time in history now, more than half the people in the world live under governments of their own choosing.

“And people are going everywhere in search of opportunity and freedom. I mean, look around this crowd today. If I had given this speech 30 years ago, this crowd wouldn’t look like it does. All the young people I shook hands with outside on the way in, they wouldn’t look like they did either. Democracy and diversity has made a world where a lot of good things have happened.

“On the other hand, suppose you come from a developing country, or you’re more pessimistic. Or you’re what my wife Hillary calls ‘your family’s designated worrier’. Most families have one. You could have given one of four negative answers:

“You could have said the biggest problem in the world is the global economy because of global poverty. Half the people live on less than $2 a day. A million people go to bed hungry every night. A billion and a half people never get a clean glass of water. One woman dies every minute in childbirth. What are you kidding me, the global economy is an asset? It’s a nightmare. Half the people aren’t in it.

“Or you could say, yes that may be true but before we’re consumed by that, environmental crises will tear the world apart in the 21st century. The oceans are deteriorating and we get most of our oxygen from them. One in four people don’t have water today and it’s going to get worse. And, most profoundly, global warming. If the climate warms for 50 years at the rate of the last 10, whole island nations in the Pacific will be flooded, we will lose the Florida Everglades and 50 ft of Manhattan island. Millions of food refugees will be created as agricultural production is disrupted. A recipe for more violence, more terror, more trouble.

The AIDS epidemic

“Or you could say, that may be true but long before that happens, we’ll be consumed by health crises. One in four people this year who die will perish from AIDS, TB, malaria and infections related to diarrhoea. Most of them little kids who never got a clean glass of water.

“If you just take AIDS alone, there are now 40 million cases. Seventy per cent are in Africa, but it’s not an African problem. It is projected that in four years there will 100 million cases. The fastest growing rates are in the former Soviet Union. On Europe’s back door.” [Clinton points at the audience.] “The second fastest growing rate in the Caribbean, on America’s front door.” [Clinton touches his chest.]

“My wife represents a million people who come from the Dominican Republic alone. There may be more cases in India now than in any country in the world, with the possible exception of South Africa. And China just admitted they have twice as many cases as they thought, a 67 per cent increase in reported cases in one year and only four per cent of the adults in China have any idea how AIDS is contracted and spread.

“So if we don’t turn this around, you’re looking at the most profound epidemic since the plague killed one quarter of Europe in the 14th century.

“Democracies will fall and you’ll have millions of young people who are HIV positive. Who think they only have a year or two to live and will be more than happy to join renegade armies and kill and plunder and make a very bleak mess of a lot of places in the modern world.

“Or if I’d asked you this question on September 10th, even then if you’d been keeping up you might have said, even before AIDS gets us, the world will be consumed by high tech terrorism. The marriage of modern weapons to ancient hatreds. Isn’t it ironic that we talk about sequencing the human genome in a world where the biggest problem is the oldest dilemma of human society.

“We still are afraid of people who are different from us. And it’s a short step from fear to dislike to hatred to dehumanisation to death.

“And all you have to do is just look around the world. From Rwanda to Sierra Leone to East Timor to the Balkans to the Middle East. And before-God bless them, my mother’s people-finally did the right thing, even Northern Ireland has caused you so much heartache for so long.

“So I mentioned these four positive things: the economy, information technology, scientific advance, democracy and diversity. And the four negative things: poverty, global warming, AIDS and terrorism.

“And I would imagine that everything had some resonance with you. Why? Because we live in a world where we’ve taken down the barriers, collapsed the distances and spread information and technology. So all of this is real to us.

“Borders don’t stop much good or bad any more. If we live in a world without walls, we have no choice but to try to make it a world where people want to be our neighbours and not our friendly terrorists. It’s not rocket science, it’s inevitable.

Funding economic, healthcare and education opportunities

Borders don’t stop much good or bad any more. If we live in a world without walls, we have no choice but to try to make it a world where people want to be our neighbours and not our friendly terrorists. It’s not rocket science, it’s inevitable.

“So what do we do? Well those of us from wealthy countries first have to promote more economic opportunities and less poverty. There should be another round of global debt relief, with the debt relief tied to healthcare, education and development, just as it was last year. The results have been stunning. Uganda took its savings in one year and doubled primary school enrolment and cut class size. There should be another round.

“We fund two million micro enterprise loans a year to poor people on all continents. The developed world should fund 50 million. Look at the success of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh and you will see what could be done if we got behind it.

“Last year we opened our markets to Africa, to Caribbean, to Jordan, to Vietnam. As well as voting to let China in to the WTO. In less than a year America had increased its purchases from some African countries by 1,000 per cent. And it did not hurt the American economy. America, Europe and other wealthy countries should do more to open our markets.”

[Clinton points at the audience]. “And you should give a special care to the Balkans. And in making sure it does not slip back in to the nightmare from which we rescued it.

“The great Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto is doing some of the most important work in the world today. He points out, correctly, that the poor people in the world today already have $5 trillion worth of assets in their homes and their businesses.

“Totally useless as a basis for credit because they are not in the legal system. Either because it’s too costly to legalise their business – in Cairo for example it takes an average of 500 days if you run a bakery to go through all the hoops it takes to legalise it. It’s cheaper to pay the guy not to pay taxes. In Bombay, if you have a little shack, you don’t have an address. You don’t have title that you can take to a court, where if you can’t afford a lawyer you can at least prove your title.

“So there’s $5 trillion worth of assets and nobody can get a loan. De Soto is spending his life trying to organise first the businesses, then the homes, get them in the legal system. So poor people who work hard and have sense can get credit and advance their family fortune, promote economic growth, be part of the market economy. It’s very important.

“The work that I did in Peru, before the Fujimori government started to decline, led to double digit growth three years in a row. We gave him a little money when I was president, but the rich countries ought to just pay for this to be done. And done as quickly as possible. It would create a whole new set of markets for us.

“The same argument applies to healthcare. We should simply fund Kofi Annan’s $10 billion AIDS health fund. America’s share would be about $2.2 billion. Britain’s share a little under half a million. For us it’s a tenth of a per cent of the budget.

“And I promise you it’ll cost us more if we let a lot of those African countries be destroyed. And if we let countries in central and eastern Europe be destabilised. And if we have 10, 20, 30 billion AIDS cases in India. We’ll pay more.”

“The same argument applies to education. A year’s worth of education is worth 10 to 20 per cent on income in a poor country. There are a hundred million kids that never go to school.

“In Pakistan, the main reason that all those kids were in the madrassas that were indoctrinating them instead of educating them-teaching them that America and Israel brought dinosaurs back to Earth to kill the Muslims, but not what two times two is-is that the Pakistanis ran out of money in the 1980s and couldn’t support their schools any more. And we,” [he pats his chest], “Didn’t come in and help.

“Now, we could put a hundred million kids in school for not very much money. Brazil has 97 per cent of its children in school and is the only developing country with that percentage. Why? They pay the mothers in the 30 per cent of the poorest families every month for their children if they go to school 85 per cent of the time. Not the fathers, the mothers. It’s a simple system and it works great.

“Last year I got the congress to give me $300 million to start a programme that offered poor children a nutritious meal, but only if they come to school to get it. You know how much $300 million will buy? A meal every school day, for a year, for over six million children. And you ought to see the initial reports – enrolments are exploding. Because the mothers, who may be ambivalent about school, want their kids to have a good meal.

“We just ought to fund this stuff. It costs money. It’s a lot cheaper than going to war. The Afghan War cost America about a billion dollars a month, and it’s about as inexpensive as war gets. For $12 billion a year America can pay more than its fair share of every programme I’ve mentioned.

“And when it comes to global warming, I just think the developed world has made a terrible mistake, especially the Americans who have fought it so far. There is a $1 trillion untapped market in existing alternative energy resources and energy conservation technologies. A trillion dollars today. The stuff on the horizon will put an end to the internal combustion engine in a way that will generate more jobs and clean up the environment.

“And I must say we had some very good leadership coming out of Europe here. And I hope when the dust settles from the current conflict, America, Europe and Japan will get together for a plan that will actually promote energy independence, reverse global warming and generate economic activity. It’s there. If we do all that, it still won’t work in some places. So I just want to say briefly: poor countries have to make some changes and we have to help.

Advancing human rights and supporting Muslims

“We need to advance democracy and human rights and good governance. You don’t find many terrorists coming out of democracy, although you do get the odd one from time to time. Not many.

“You don’t find democracies sponsoring terrorism, and they’re more likely to honour human rights. But a lot of these democracies are new democracies, so they need help in increasing their capacity to deliver for their people. That also is important.

“And we need especial care for the debate now going on in the Muslim world. And I just want to say a little about this. I was the first president ever to observe the feast of Eid al Fitr every year at the end of Ramadan. The first to bring large numbers of Muslims into the White House to consult on domestic and international issues.

“One of the best things I think President Bush has done is to go to a mosque and meet with Muslim leaders soon after September 11th, to have a breaking of the fast dinner for Muslims in the White House during Ramadan, to make it clear that America and the West are not the enemies of Islam.

“But we are seeing a terrific debate going on within the Muslim world. And many Muslims believe that the West in general, and America in particular, are hostile to their values, to their way of life, to their economic wellbeing.

“This debate is raging in the Middle East, in central Asia, I would imagine in Great Britain, and I can tell you in New York. Recently a Muslim chaplain was put on probation for allegedly defending bin Laden in a prison in New York.

“There’s an Afghan mosque in New York City where the Imam, the day after September 11th, made a wonderful, wonderful statement condemning the terror as a violation of Islam. A minority of his congregation walked out of the mosque and began to worship in the parking lot, because they were pulling for bin Laden.

“A conservative activist recently got in trouble in America for bringing people into the White House. In the administration’s effort to reach out to Muslim Americans they allegedly brought people into the White House that had supported terrorist networks.

“This debate’s going on everywhere, and we have to get into the middle of it because we have to strengthen the forces of moderate Muslims.

I will guarantee you that most Muslims in the Middle East, even today, don’t know that the last time that the United States and the United Kingdom used military power was to protect the lives of poor Muslims in Bosnia and Kosovo. They don’t know that 500 Muslims died in the World Trade Center. They don’t know that the FBI recently asked for 200 Arabic speakers to help America fight terrorism-and 15,000 people volunteered.

“They don’t know that when 18 American marines were killed in Somalia in 1993, in that raid you probably heard Mr bin Laden bragging about. They don’t know why the Americans died. The United Nations asked the Americans to arrest Mohammed Aidid because he had murdered 22 of our fellow peacekeepers. All Pakistani Muslims. They don’t know how many were murdered in the African embassy bombings. Two hundred Africans were killed.

“And they certainly do not know that the United States proposed – Israel accepted but the PLO rejected – in December of last year and January of this year, the most sweeping terms to provide a Palestinian state of the West Bank in Gaza, and protect Palestinian and Muslim interests in Jerusalem and on the Temple Mount in all of history. Far more than anybody ever dreamed the Israelis would agree to. And the PLO said no. They don’t know that. So we have to get our story out. And finally let me say this. You may consider this naïve, I think this is the most important thing I’ve said.

Our common humanity

… if you want this world without walls to be a good home for your children, we’ll have to make it a home for all the world’s children.

“We all have to change. The poor people of the world cannot be led by people like bin Laden who think they can find their redemption in our destruction. But the wealthy people of the world cannot be led by those who play to our self interests in a short-sighted way and tell us that we can forever claim for ourselves what we deny to others.

“We all have to change. It all comes down to which do you believe is more important: our differences or our common humanity?

“This crowd in Afghanistan, like fanatics from time immemorial, are absolutely convinced our differences are more important. They think they have the whole truth. If you share it, your life has value. If you don’t, you’re a target. Even if you’re just a six year old girl who went to work with her mother at the World Trade Center on September 11th. They think a community are people who look alike, think alike and act alike, and if people stray you have somebody there to beat them back into line.

“Most of us believe – indeed you could argue that the whole premise of a university requires the belief – that nobody has the truth. And arguably the more religious you are the more you should feel this. Because if you are a child of God, however you define that and worship it, you must surely feel the finite nature of your life and your mind.

“So must of us see life as sort of a journey where hopefully we stumble toward the truth. And we learn things from each other. So we think everybody ought to make the journey. And most of us believe you can be in our community, as I said earlier, if you simply accept the rules of the game: that everyone counts, has a role to play, we all do better when we work together. That’s what this is all about.

“This answer is easy to give. You’re all sitting there saying, ‘that’s right, that’s right’. But this answer,” [he points his finger at the audience], “is hard to live. Our boxes are real important to us.” [He points to the audience, chair and himself in turn]. “Student. Professor. Indian. British. Irish. Men, women, God forbid. Football, rugby. Tory, Labour. You think about it. Think about how many of your categories you think about between now and the time you get home tonight.

“We have to organise reality into these little boxes otherwise we couldn’t navigate the world. But then somehow along life’s way it dawns on us, that if we all we are is the sum of our boxes, we will never really be connected to the rest of humanity. And so the way we understand reality is helpful to us but it isn’t the whole ball of wax. So you come to the conclusion that our common humanity is more important. But it’s hard to live.

“When I was the age of my daughter and the students who are here, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were murdered because they tried to reconcile the American people to each other. And they did not want to be reconciled to their common humanity.

“Perhaps the greatest spirit to live in my lifetime, Mahatma Gandhi was killed by a Hindu. Not a Muslim, not a Tamil, but a Hindu. Why? Because Gandhi said India should be for the Hindus and the Muslims and the Tamils and the Jains and the Sikhs and the Jews and the Christians. And the Buddhists and whoever else wants to show up. And this Hindu guy was really mad because there was Gandhi outside the box again. Couldn’t be a good Hindu, couldn’t be a good Indian. So he murdered him. After he gave his whole life, 78 years, to bringing India into being. And getting you off their back.” [A belated laugh from the audience as they realise this is a reference to Britain.]

“In an instant Sadat was murdered, not by an Israeli commander but by an Egyptian. Why? Oh he was not a good Muslim or a good Egyptian because he wanted secular government and peace with Israel. And one of the best people I ever knew in my life, Yitzhak Rabin, was murdered after a lifetime defending his country. Not by a Palestinian terrorist, but by an Israeli who thought he was not a good Israeli or a good Jew because he wanted to lay down a lifetime of fighting and give the Palestinians their homeland and find security for Israel in a world with more partners and fewer terrorists.

“The answer is easy to give but hard to live. But this is what this whole deal is all about in the end. Look, we’re going to win this fight in Afghanistan. We’re going to make our defences better.

“But if you want this world without walls to be a good home for your children, we’ll have to make it a home for all the world’s children.

“Thank you very much.”

A decade later in 2012, Bill Clinton returned to deliver a second public lecture. He was in conversation with the actor and humanitarian Ashley Judd, in the Old Theatre, Old Building on 11 July 2012.

In 2001, Clinton had told the audience at LSE that the answer to a better world is understanding that our common humanity is more important than our differences – “this answer is easy to give but hard to live.”

Perhaps his own solution was to create the William J Clinton Foundation, which was established in 2002 with the mission to improve global health, strengthen economies, promote healthier childhoods and protect the environment. He was back at LSE to mark the tenth anniversary of the Foundation.

Ashley Judd introduces the event as being within the context of an international family planning clinic hosted by the British government and the Gates Foundation. Due to HIV and AIDS, family planning fell off the international radar and a consequence is continued disempowerment of girls and women in regulating their own fertility. “The goal of the summit … is to empower an additional 120 million girls and women of reproductive age by 2020 with a choice of family planning options”.

Judd goes on to say that the event is also to celebrate President Clinton and the Clinton Global Initiative, “and find out the inner workings of this brilliant mind and the foundation and how it’s impacting so many parts of our world.” A Clinton Foundation video is shown to the event audience, focusing on asking and answering “how” good intentions can be made into real changes.

Clinton thanks Ashley Judd for the introduction and Professor Calhoun (Director of LSE) and LSE for having him back . “I always feel like I’m an academic pretender when I’m at LSE.” He thanks the Reuben Foundation for their support and the government of the United Kingdom and DFID, the Department for International Development, a partner in fighting malaria, AIDS, and building healthcare delivery systems around the world. Judd says that she will use a timer to keep the conversation on track!

Redesigning the AIDS medication business model

I personally believe there’s a lot to be said for helping people figure out how to do things.

Ashley Judd: “In the video that we just watched, we saw that no matter what the problem is your foundation is trying to solve … you do ask the ‘how’ question. Please talk about this question, how it guides and informs your work, and is it sort of a guidance note for every issue that you tackle?”

Bill Clinton: “Well let’s start with the thing that got us going. More than a decade ago, before there was a global fund on HTD and malaria, before there was the American PEPFAR programme, there were only 200,000 in developing countries and even middle income countries who had AIDS and needed the medicine to stay alive who were getting it. And 130,000 of them were in Brazil, because they had their own pharmaceutical industry and they could either produce generic medicine or use it to lever the prices down. So there were already five or six million people who needed the medicine to stay alive – and nobody was getting it.

“So in the beginning I just was going around trying to raise money and then it occurred to me that once we started looking at it, the generic AIDS medicine at the time was selling for about $500 per person a year. Much less than we pay in the United States – £10,000 at the AIDS clinic around the corner from my office in Harlem in New York – but still an enormous amount of money if you’re a very poor country with a high infection rate and a low tax base.

“And so we examined this £500 and we realised that there was a business model behind it that seemed to be the only one available to Ranbaxy and Cipla and the other pharmaceutical major suppliers of AIDS medicine, the generic one.

“It was essentially a low volume business and so they needed a high profit margin, because it was both low volume and the payment was uncertain – and by the way the delivery system wasn’t so hot.

“So basically it’s the way, if you were in a small town, you would run a jewellery store business. I mean think about it, if you run a jewellery store you have lots of inventory because people want to look at different watches and rings and things. And so you have to have a high profit margin, and besides payment’s uncertain – someone might give back the engagement ring. A wonderful American journalist had his first fiancee give his engagement ring back, and he realised he didn’t know what to do about it so he wrote a fabulous book on this history of diamonds and turned it into something good.

“But anyway, it occurred to me that if we could get a guaranteed payment stream and improve the supply chain, we could turn this whole AIDS business into a low profit margin very high volume absolutely certain payment business. And it didn’t just occur to me, it occurred to the guys who were working with me, beginning with Ira Magaziner, who was with me at Oxford over 40 years ago. We looked at it and said, this doesn’t make any sense, this business model. It was so disorganised that the Bahamas were paying $3,500 for this $500 medicine because it was going through two agents and no one knew what the price was.

“So we essentially redesigned the market. I hadn’t been out of office long, so I went to these companies and they were mostly Indian, one in South Africa, and they knew me and the leaders of the countries knew me and I said, I give you my word. If you don’t make more money doing it our way, we’ll undo the contracts. But this is insane for you to have this kind of markup on a generic drug just because you’re not getting paid and because the volume’s so low. Then I went to first Ireland and Canada, two countries I had very close relationships with and the leaders of the countries were still people who had served with me, and they were spending money on this. I said, I want you to give me each $20 million a year for five years but I don’t want you to give me the money now, I won’t touch a penny of it. I just want you to promise me that I can greenlight the money. And you pick the countries where you want the AIDS medicine to go. But that will give me enough to get volume up enough to get prices way down.

“So we took the prices from $500 to $140 to $120 to $90. Then when the old three pill a day regime was turned into a one pill a day, we immediately got that down to $200 and then started driving that down. The children’s medication we took from $600-fewer ingredients but much smaller volume sales-down to $60. All because we asked ‘how’.

“I do a lot of work with the Gates Foundation and they did this wonderful conference with you [LSE] and essentially they like to fund things and then fund implementers-so we just started trying to figure out how to do that. We do it in lots of other ways on things like reducing carbon emissions. We had a contest a few years ago, when I was working with a group called the Seed 40-that actually started here in London when Ken Livingstone was Mayor, but has been continued under the current Mayor and is now chaired by the Mayor of New York City-to offer global certification to people who promised to build totally carbon neutral developments. Zero emissions. Residential, commercial or mixed. And two of them are here. And we’re about to get them finance, about to get going.

“I personally believe there’s a lot to be said for helping people figure out how to do things. In the poor countries normally it involves building systems they don’t have, which make life predictable and results positive. In wealthy countries, and sometimes in rising countries, it normally means reforming systems or finding alternative ways of dealing with it because rigidity and self interest have overcome advancing some public costs.”

Creating the Clinton Global Initiative

Judd: “So from there, the Clinton Global Initiative has, within women’s issues in particular-which is of course the focus of the current family planning summit-resulted in 135 commitments with an estimated value of $1.7 billion. But that’s just within the girls and women track. In total since the foundation was begun, 2,100 commitments totalling $69.2 billion: from initially asking this question of ‘how’, being incredibly involved in the detailed work, leveraging your contacts, relationships, personality, your brilliance”. [To the audience: ‘whatever, I’m a bit of an adoring fan’] “You mentioned something about helping poor countries build infrastructure and systems. So take us to the beginning of CGI, now that we’ve heard some of these dazzling figures about what you’ve done.

Clinton: “Well first I realised that I didn’t have a big or wealthy foundation and never would because I was interested in trying to save as many lives and create as many opportunities as possible.

“So I have about 1,400 people working for our foundation, not counting the volunteers that are legion, and we operate in 40 countries that are mostly doing healthcare and energy work. We do work on agriculture and we do a lot of work on reforestation, carbon credit, waste energy, a lot of that stuff. And then we have a major initiative in the United States against childhood obesity.

“But I realised that I have to go get money for all these things and a lot of the donors like working with me because our overhead’s lower than most other people. But nobody gave me $100 million, I don’t have a big endowment, I just do this, I help. So the Gates Foundation is one of our best partners. They put millions of dollars into projects that we work on together every year and we figure out how to do it.

“But I realised that first of all there were a huge number of people who cared about things that I cared about but could never get into, and a huge number of people who knew how to do things that neither I nor anyone working for me knew how to do. That’s how we started this global initiative.

“We just said well – all the leading politicians show up in New York around the United Nations, so what if we had a conference there? And we invited NGOs, philanthropists, business people and the leaders who show up, and we talked about these issues but it was different – everyone actually had to commit to do something and then we would help them do it. I think networks produce better decisions than you and I do alone in a closet. People know more things together, they figure out how to solve problems.

“So we started this meeting. I had no earthly idea if anybody would come to this. I mean whoever heard of actually charging someone to come to a meeting so that they could make a commitment to spend more money, more time, more something else.” [Laughter from the audience]. “But it turned out people wanted to be asked to come to a meeting where they made a commitment. And so we now have to flesh out the numbers that I actually mentioned.

“The Clinton Global Initiative meets every year, then we do one just on the American economy, which we will do until we return to full employment. We had one in Hong Kong for Asia which I had to suspend while Hillary was Secretary of State for good reason. In order to do one around the world and to make the economics work and to keep the entry fee fairly low, you have to have sponsors. And if your wife is Secretary of State and you get sponsors in another country they may be doing it just because they believe in it, but it opens up too many questions of conflicts of interest. So we suspended those, but if she leaves the State Department in January then I expect we will have one in 2013 in Latin America and then shortly thereafter in Asia, because they were interested in it.

“Then we had these full time working groups that spun out of CGI. They meet all year long. The most important thing is, our regular members have to work for a year on their new commitment. They announce it and then set about implementing it. It turns out people were dying to be asked to do something but they wanted to make sure they could answer the question that is, they wanted to make sure they weren’t wasting their money or wasting their time or wasting their skills. They found that if they got in a network of people who cared about this, they could figure out at least what the most likely successful path was. That’s how it happened and it just kind of grew like topsy, it just kept going.”

Judd: “Is there anyone here who’s ever been to a CGI meeting? I highly recommend it. It is an absolute and total ball. The first time I came to the Fall meeting, it was social, it was inspiring, it was really stupendous. And I’ve had the privilege of being appointed one of the CGI leads by the President and my cohort is working. We started with rethinking refugees. Of course we want to eradicate the underlying causes and conditions that create displacement, but we also wanted to make an immediate improvement in conditions in camps. I’m in Prague trying to star in a darn TV series and I have to go to Congo with my CGI lead – wasn’t that an interesting out to negotiate in my contract! So when we say commitments and full time working groups around the year, that’s for real.

“So tell us a little bit about the people who show up. You’re all about partnerships, you’re about leveraging the private sector, civil society, having governments involved when they have the capacity, so for example if there are folks here with small businesses, what is their place within CGI?”

Building partnerships, infrastructure and systems

Clinton: “Well I’ll give you a great example. We have a Haiti working group headed by Denis O’Brien the chairman of Digicel. Digicel and Voila, the two major cell phone companies in Haiti, just got the last $3 million of Bill and Melinda Gates’s Foundation $10 million challenge money for entrepreneurial advancement. Why? Because they are providing the poorest country in the Caribbean banking services by cell phone.

“Now, why is that important? Because 20 per cent of Haiti’s GDP comes from remittances by the Haitian diaspora in the US, Canada, France and the Caribbean, primarily that’s where most of the Haitian diaspora is. The bank’s ownership is highly concentrated, not particularly competitive and if you own one of these banks you can make enough money every year just on the fees you earn converting what the Haitians send from the US and Canada into Gourdes and giving it to their families.

“When we started it was hard to access normal banking services as individuals and if you were a Haitian entrepreneur it was virtually impossible to get an affordable small business loan, they started at 45 per cent. And in an economy where interest rates were virtually zero globally.

“When this happened I got Carlos Slim and a Canadian friend of mine, Frank Giustra, who agreed to put $20 million into a small business loan fund. We make small business loans at anything from 3.5 to 7 per cent. And those two things, plus getting mentors to go down there and work with people, have created access to banking services for ordinary people and access to small business loans.

“It’s one thing to be for it and another thing to figure out how you’re going to wade through the thick of it to figure out how this can work. And what I think is going to happen is, there are some younger people in Haiti now involved in banking, my friend Rolando Gonzalez-Bunster there knows them all. I think eventually, after a couple of years, when we show that this fund works we’ll be able to give this to a bank under a Trust that will commit them essentially to have a small business loan facility. For the first time ever they will actually have affordable small business loans. I’ll give you another example.

You have to be willing to stop when you’re failing.

“I was trying to help in Harlem. When I moved to New York and I moved into the neighbourhood, the small business community was an important part of the culture of Harlem. But there were these businesses that had been there 30 years and they didn’t even have their records computerised. They didn’t even monitor their inventory. They had no capacity to check with their customers to see whether their product choices were going to keep them competitive.

“This is another thing, you have to be willing to stop when you’re failing. Real important. So first we got New York University Stern School of Business, the Black NBA Association, the African American association involved in property development and some big accounting firms. And we did all this work in Harlem to essentially give Fortune 500-like business consulting services to small businesses. It worked for a few of them but it was a totally unexpandable model. The cost for business was too high.

“So instead we went to Inc Magazine which was a small business magazine in America, an entrepreneurial magazine, and we made a partnership with them to find successful entrepreneurs who would work one on one with businesses, not just in Harlem but in any other city in America.

“We started by trying to save them in the aftermath of the financial collapse and then helped them to grow again and that’s proved to be just as successful and perhaps even slightly more successful. Much less costly and far more rewarding. But that’s the sort of thing that when you say you’re going to answer the ‘how’ question, you have to acknowledge you’re not going to get the right answer the first time every time. And when you’re failing you’ve got to be willing to stop, either because it’s just flat out not working, or the cost per success is too high given the resources you have to deploy on the problem. So that’s a good example.”

Agriculture in Africa

Judd: “And the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result. [Clinton: “Yes.”] “So it really speaks to a willingness to have a rigorous inventory of the process and amend the process when necessary. So there are a lot of directions we could go now but one of the things about which I personally see you become most excited was agriculture in Africa and the use of technology. So tell us a little bit about that, and some people in this room may know that there is another impending famine crisis, particularly in sub Saharan Africa. Just tell us a little bit about your ag work and why you get so excited?”

Clinton: “Well first, if the world in fact goes from seven billion to nine billion people by 2050, we’ve got to figure out how to feed them. And there are basically two competing models here. There is the: let the people with money who can’t produce enough food for themselves – China, Saudi Arabia and others – go buy or rent the land and clean it off and get rid of these poor, inefficient smallholder farms and go to a highly mechanised agriculture. And maybe the country gets a good deal where the land is, maybe they don’t.

“Or, maximise the growth potential of agriculture in the places which could produce more food so that they first feed themselves and then have the capacity to export. Now I’m over-simplifying, there are lots of layers on this. But I strongly favour doing the latter because starting about 30 years ago the whole developed world backed out of trying to support indigenous agricultural development in Africa and in the poorer countries of Latin America and south east Asia, with this crazy theory that somehow they could just leapfrog that and go into the industrial era and all of us European and American farmers with our highly subsidised systems would kindly give them the food so they could make this leap. So there was a heavy dose of self interest involved. But it’s very complicated. You see it in the severe water problems the Chinese are now having, there are lots of examples of this.

“So I just thought we would start on a small basis in Africa and just see what was possible. We started looking at these farmers in Malawi and Rwanda and Tanzania and other places to see what they were doing. And I remember I went to Rwanda first to help them with their healthcare system.

“And so we went out and talked to some of these farmers and I got down and started digging in the soil and this guy, this farmer started laughing and he said, ‘many westerners come here and tell us they are going to give us money to do great things, you’re the first one that ever got down on his knees and dug in the soil’. I said, ‘well that’s because I lived on a small farm like yours when I was a kid’. And we started talking.

“And what we found was that if you did the equivalent of what we do with AIDS drugs, that if you got the scale buying up, with good seeds, good fertilisers, you help people manage the pith, and most important of all if you just found a way to store the food and take it to market you would more than double the income of virtually every smallholder farmer and virtually every poor country in Africa. And you could therefore dramatically increase the production.

“The one thing the farmers have done a good job of there is preserving the topsoil. In most countries there’s been very little destruction of the topsoil. So we started working there. And the worst we’ve done anywhere is to double farm income. That’s the poorest performance.

“I consider that a failure actually, if we only double farm income, because in really poor places where there are no roads and farmers not only have no access to mechanised transportation they don’t have their own access to animal-drawn transportation. They give up half their farm produce price just to take the food to market. So they lose half their income right off the bat for someone else to take it to market. And the minute it gets on the cart they lose control over the quality of the food when it arrives at the market and that whole nine yards.

“So we say, well the worst we could do is at least take the food to market for them. I started getting enough money to take the food to market. And we backed up into that more economical seeds, more economical fertiliser, diversification of crop growing practices, food processing operations and on and on and on.

“But I’ll just give you one example. All these famines in the Horn of Africa. That’s Somalia which is riven by strife, northern Kenya, Djibouti and extreme eastern Ethiopia east and south of Addis. Most of the farming area in Ethiopia is south and west of Addis but if you go there in most years you will see what great farmers the Ethiopians are, what a bumper crop they have. How if they had the storage, cooperative marketing, they could transfer a lot of that food there and the rest of the world that keeps sending food in there could finance the transport of the food east and drastically undermine and reduce the number of severe famines in the Horn of Africa.

“And we just keep pinning more and more money on the same emergency bail-out instead of trying to create circumstances in the region which would enable them to feed themselves and even to deal with their own emergencies better.

“So even though this is a small part of what my foundation does, I think given what’s happening with population and the need for sustainable agriculture, instead of things that use more resources on an unsustainable basis, I think it might have the biggest potential for copying or replication, of anything we do. It’s just crazy what these people are up against. It’s nuts.

“And every place I have gone – when I worked in the tsunami area in Indonesia, in Banda Natchez after the tsunami, and all through the tsunami affected areas, and then all the stuff we do in Africa, and everything we’re doing in Haiti now, trying to bring the mango crop back.

Mangos and fish in Haiti

It’s a big mistake to give up on smallholder farmers in the developing world.

“Forty per cent of Haiti’s mango crop is lost every year. Even though every mango grown in Haiti can be sold on the street for high dollar in New York City in our open markets in Manhattan alone. We can move the whole crop and give them a lot of money. Forty per cent of the crop is never taken there because when the mangos come off the tree they are so bruised by the time they get to the packing and shipping that they just have to be sold on the street in Port-au-Prince. Which is nice for them, they get the mangos. But they have to sell it for like a third of the price.

“We have lots of other examples. There was a picture – I don’t know if you saw it in the little film – of Valentine Ambe who is my hero. He’s from Cote d’Ivoire, he had a Fulbright Scholarship in marine biology to the University of California at Berkeley – and he turned it down. First person from Cote d’Ivoire ever to get one, they said ‘how can you do this, you’re going to get a Nobel Prize, you’re a genius’. He said, ‘because I don’t care about winning a Nobel Prize, I want to feed poor people. Eventually we’re going to have to grow fish in a more responsible way, so I want to go to Auburn University because they know how to grow fish.’ True story.

“So then he decides to move to Haiti and the entire talapia operation he runs now in two big centres is entirely solar powered. The fish are kept cold by generators powered by solar power. Haiti has a huge protein shortage and the only thing he doesn’t economise on is food. He feeds them organic food made in Virginia, the most expensive fish food you can buy. He said, ‘I’m tired of poor people being guinea pigs for the absolute dreck that fish are fed around the world and I intend to do this.’ Everything else, he’s got lower cost production that anything in the world except for the feed. And all the farmers more than doubled their income working with him.

“It’s a big mistake to give up on smallholder farmers in the developing world, thinking somehow we can leapfrog this. We need to go back to growing food and let people be self-sufficient. Then if we need some bigger production, then if we need to do something else to feed the world, we can cross that bridge when we come to it. But it is wrong to tear up people’s centuries-old lifestyles and patterns before you even know whether what they’re doing can be made economically viable. My experience is that there is an almost unlimited ability to increase their economic potential.

“Otherwise I don’t have strong feelings on the subject.” [Laughter from the audience].

Clinton’s motivations and values

The only thing that makes sense is to try to develop a path to a shared future where we have shared responsibilities and shared prosperity.

Judd: “We are familiar with your post-presidential career, which is becoming one of the most impressive in terms of our presidents who have left public office and gone on to remain very dynamic citizens of a changing world. What role does your faith, does your strong feelings, does your morality, your ethics play in all of this? As you’ve seen, meaning the audience, your interests really know no bounds. How do you keep going and what sustains you?”

Clinton: “Well, first of all, if you think about the life I’ve had and the improbable life I’ve had. There have only been two governors of tiny states ever elected President of the United States. The odds of my ever becoming President were one in tens of millions or something ridiculous. And I think that I would be kind of a reprobate if I didn’t do this.

“Secondly, I don’t play golf well enough to play on the tour. [Laughter]. “I don’t play my saxophone well enough to make a living at it any more. And I love this, this is fun. This is not a selfless deal, I have a lot of fun doing this. I find this immensely rewarding.

“The third reason is, I believe that we moved into an era, maybe just in the nick of time, to an economy that is based on information technology, as well as all the old traditional elements, at a time when the world has become completely interdependent.

“But we can’t make up our minds what that interdependence is going to look like. Interdependence just simply means you can’t get a divorce. That’s all it means. You can’t get away from each other. It might be positive, it might be negative, it might be both. But to pretend that the United States and China are not going to share a future is nuts. Or the US and India. Or Europe and – you pick, fill in the blanks.

“So the world now is awash in a kaleidoscope of questions that all come down to this: are we going to share the future or try to take it away from someone else? Will we adopt a conflict model or a cooperation model to resolve our differences and to meet our own objectives?

“And I basically believe we’re in a world that is where growth and opportunity and even basic humanity is drastically constrained by severe inequality in the unavailability of jobs that pay an affordable living. By instability that has brought on, not only the consequences and aftermath of terror but the financial crisis. And by a totally unsustainable use of resources because of climate change and local resource depletion.

“The only thing that makes sense is to try to develop a path to a shared future where we have shared responsibilities and shared prosperity. And where people respect their differences but think their common humanity matters more. No other strategy will work. The only place conflict still works is in politics. Constant conflict. But in the real world what works is creative cooperation.

“I do this, first because I think I should. I’m essentially – in spite of my happy-go-lucky demeanour – a Calvinist at heart. You know, I’d feel guilty if I didn’t do it. But mostly I do it because I’m pretty good at it and I love it and it’s fun. It’s more fun than anything else I could do.

“I think I’m morally bound to do it because I don’t think we have any other way in the future. I don’t want my daughter and the grandchildren I hope to have and all of you young people here to live in some sort of science fiction world that is bleak and conflict-driven. It’s just not necessary.

“I think the 21st century is either going to be the most interesting time in human history or it’s going to be pretty bleak. And I don’t think that we’ve decided yet. But more than the specifics is the attitude. Nobody knows everything. Everybody’s wrong sometimes. And nobody’s wrong all the time.

“That’s my problem, I’m having this fight all the time with this tea party crowd in America, they think they’re all right and it’s going to be my way or the highway. And I said, ‘look, a broken clock is right twice a day.’ [Audience laughter]. “And nobody’s right all the time, and we’re all compelled to spend our poor little existence, fleeting through time between the extreme of being right more than twice a day and not being right all the time.

“If we can have that attitude and value everybody, we have a chance to get through the thickets that await us. But that’s why I do this. I really do believe it’s a great time to be alive.

“But we haven’t made this fundamental decision about whether we’re going to share the future or fight over it.”