In this article, Joss Harrison examines the failed attempt to establish an Anglo-American military airfield on the Indian Ocean island of Aldabra. After exploring existing explanations for the failure of the project, Harrison argues that it was mainly abandoned for the lack of Anglo-American cooperation.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the United Kingdom (U.K.) and United States’ (U.S.) actions in the establishment of the British Indian Ocean Territory (B.I.O.T.) have been subject to increased public and scholarly scrutiny.[1] The B.I.O.T. is a British overseas territory made up of islands coercively separated from Mauritius and Seychelles for defence uses. The military facility on Diego Garcia, as the only successful development in the territory, has received the lion’s share of critical attention,[2] while other plans devised by Britain and the U.S. for the B.I.O.T. have been comparably neglected.

Foremost among these lesser-known cases stands the failed attempt by the U.K. and the U.S. to establish a military airfield on Aldabra in 1967. Aldabra is an atoll noted for its extraordinary biodiversity and its limited degree of human disturbance, making it invaluable for the study of evolutionary biology. In this article, I argue that the Aldabra project failed principally due to ineffective coordination between the U.K. and the U.S.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALDABRA

The U.K. established the B.I.O.T. in December 1965, with the U.S. covertly contributing half of the associated costs.[3] This reflected a new defence strategy urging the acquisition of sparsely populated islands to serve as politically insulated military outposts.[4]

On 28 July 1967, the Defence and Overseas Policy Committee (D.O.P.C.) of the Cabinet authorised Secretary of State for Defence Denis Healey to proceed with a military airfield on Aldabra, subject to securing a 50% financial contribution from the U.S.[5] Aldabra was to be a British-led project, with the U.S.’ role limited to financial support and attendant usage rights. Healey argued that the staging post would increase the U.K.’s operational flexibility, offering a route eastward for British aircraft – via Ascension and Aldabra – independent of other countries.[6]

However, in November 1967, the project was abruptly cancelled. Healey publicly attributed this decision to the U.K.’s devaluation crisis, which necessitated £100 million in defence cuts by 1971; cancelling the Aldabra project would save £4 million in 1969 alone.[7]

EXISTING ARGUMENTS FOR ALDABRA’S CANCELLATION

To take Healy’s statement at face value and to attribute the abandonment of the Aldabra project to economic conditions, as does D.R. Stoddart, [8] is not entirely satisfying. Given that the savings could presumably have been found elsewhere, the devaluation crisis should be understood as the context in which the decision was made, not a straightforward explanation for the project’s failure.

The existing scholarly literature on this case is extremely limited. David Snoxell emphasises “pressure from the conservationists.”[9] David Vine attributes it to scientific opposition and the military spending cuts.[10] Yoichi Kibata, finally, lists American hesitance, scientific opposition, and opposition from the Indian Government as the reasons for the project’s abandonment.[11] The common thread linking Snoxell, Vine and Kibata’s arguments is their emphasis on scientific opposition. There were two main strands to scientists’ arguments against the base project. Firstly, they warned that Aldabra was home to a large colony of frigate birds whose size, population density and altitude risked heightening the frequency and severity of aircraft collisions.[12] They feared that the U.S. and the U.K. would ultimately resort to exterminating the bird population to eliminate this threat. Secondly, scientists argued the base would irreversibly alter an ecosystem unique for its minimal human interference, thus squandering an opportunity to study evolutionary processes. Armed with these two arguments, the transatlantic scientific community, particularly the Royal Society in Britain and the Smithsonian Institution in the U.S., mounted a public campaign against the project.[13] These bodies also pressured government officials in private, notably at a meeting between Healey and the President of the Royal Society, Patrick Blackett, on 22 May 1967.[14]

However, the importance of the scientific opposition should not be overstated. Privately, officials derided the Royal Society for its failure to generate any substantial press or public reaction.[15] Its quiet diplomacy was hardly more effective; when Healey met with Blackett, he was candid that the project would likely go ahead despite the latter’s objections.[16] British and American officials also disputed the substance of the scientific arguments. They argued that Aldabra’s ecosystem had already been fundamentally altered by the island’s small human population, and that the base would not pose unacceptable scientific damage if strict regulations were imposed.[17] Meanwhile, Healey and McNamara agreed that the bird strike problem did not constitute an “overriding argument” against proceeding.[18] Officials remained hopeful, despite a pessimistic report from the U.K. government’s bird strike expert in October 1967, that the frigate birds would relocate themselves once disruptive construction work started and mild interventions were implemented.[19]

AN ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATION: ANGLO-AMERICAN MISCOORDINATION

A far more serious reason for the project’s failure was the ineffectiveness of Anglo-American coordination. The first cracks emerged in March 1967, when the U.S. abruptly pushed for the U.K. to formally confirm its intention to develop Aldabra within the next three weeks. U.S. members of Congress would not approve FY 1968-69 funding for the project in the absence of official confirmation of Britain’s involvement.[20] British officials, however, could not formally decide on Aldabra before the completion of a Defence Review focusing on Britain’s overseas military presence, which was scheduled for the summer of 1967.[21] Ultimately, a budgetary workaround was found on the American side, but this moment of tension proved microcosmic of a persistent misalignment between the two sides.

On 16 August, following the D.O.P.C.’s approval of the project, Healey addressed a letter to McNamara asking for confirmation of American participation.[22] Prior to this point, the U.S. had given the U.K. every indication that it intended to support the project; it had provisionally agreed to finance half of the project as early as August 1966.[23] Britain therefore had every reason to expect that a positive response to Healey’s letter would be forthcoming. However, in the event, McNamara was never to reply, and the U.S. provided no clear guidance as to whether or when a positive outcome might be received. In the meantime, as the U.K. waited in vain for any signal of U.S. intentions, deadlines began to slip. First 12 October and then 7 November were proposed as dates to make the joint announcement, yet both came and went without the necessary confirmation from the U.S.[24] This was more than just an inconvenience. The Ministry of Public Building and Works had warned that if the green light were not given by November, the project timeline would have to be pushed back by a year due to climatic patterns on Aldabra. Healey was clear that this delay made the project significantly less attractive.[25]

Equally, Britain made promises that it was unable to keep. For example, Healey bullishly promised McNamara a report on differences of opinion that existed within the scientific community regarding the base project.[26] This was supposed to help McNamara face down lobbying from the American scientific community.[27] However, M.O.D. officials ultimately proved unable to identify marked divisions among the scientists and the hurried, inconclusive report they produced was quietly shelved.[28] By their own admission, British officials lacked a firm understanding of how the U.S. intended to use the facility, leaving them unsure of how to secure its approval and sceptical of its sincerity.[29] At the decisive stage of the project, communication between the two sides had fallen into disarray.

The year-long delay to implementation brought into view by the U.S.’ obfuscation, and Britain’s persistent inability to garner the U.S.’ intentions despite having staked the project on American financial participation, proved fatal. Under these conditions, when the devaluation crisis struck and forced cost savings upon the M.O.D., the cancellation of Aldabra presented itself as a palatable option.

CONCLUSION

Overall, Anglo-American miscoordination was a critical factor in the abandonment of the Aldabra project. This has not been appreciated by existing historical accounts, which in emphasising economic and scientific factors have obscured the failure of British and American government officials to communicate effectively and openly with regard to Aldabra. This reframing of the Aldabra story is significant for several reasons. Firstly, it draws attention to an under-studied aspect of the history of the B.I.O.T. Diego Garcia is increasingly in the news as Mauritius seeks to restore its sovereignty over the atoll, but few are aware of how close the U.K. and U.S. came to establishing a second military base in the territory – and how their final decision not to do so ultimately rested more on miscommunication than virtue. Furthermore, for the field of colonial history more generally, it is important to study failed projects such as Aldabra. These cases elucidate the fundamentally tenuous nature of imperialism, in contrast to the commanding image that powerful states prefer to present.

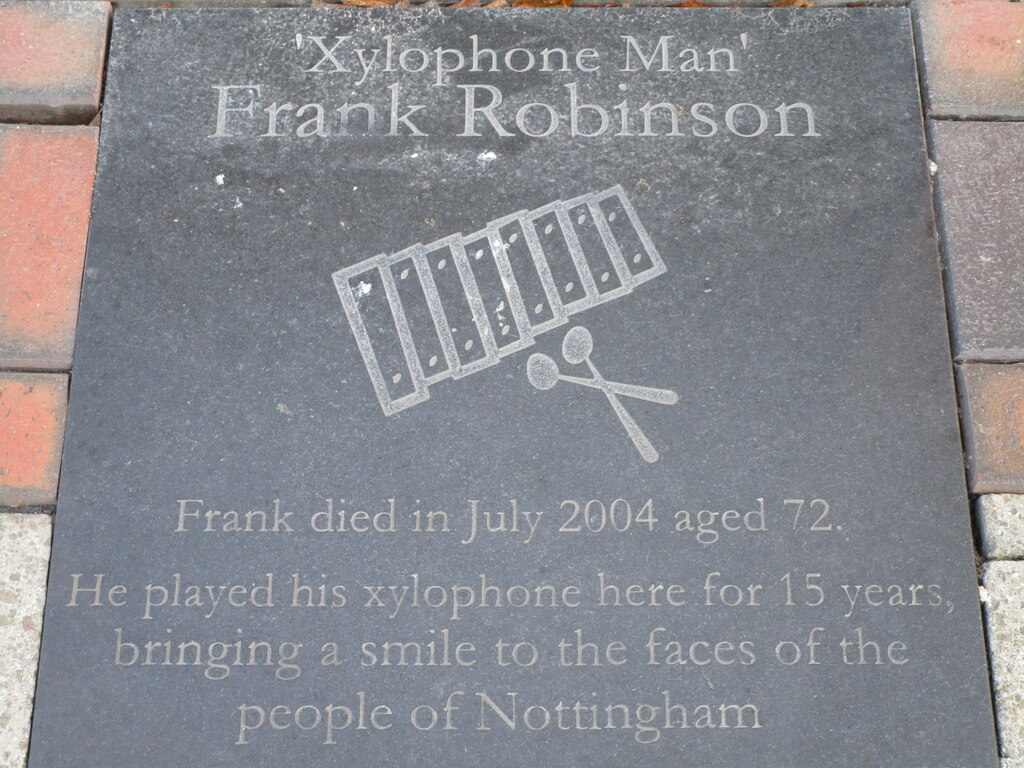

Featured image: Robert McNamara (right) meets Denis Healey (center) at the Pentagon. Courtesy of NARA & DVIDS Public Domain Archive.

[1] Loft, Philip. ‘British Indian Ocean Territory: U.K. to Negotiate Sovereignty 2022/23’, 6 May 2023. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9673/.

[2] For example, Sand, Peter H. United States and Britain in Diego Garcia: The Future of a Controversial Base. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009; Vine, David. Island of Shame. The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009.

[3] ‘B.I.O.T Administration – B.I.O.T Laws – the Ordinances’. Accessed 6 May 2023.

https://sites.google.com/site/biotgovernment/biot-government-royal-prerogative-orders-in-council/laws-of-the-biot.

[4] ‘Airgram from the Department of State to the Embassy in the United Kingdom.’ January 21st, 1964, in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964-1968, Vol. X: National Security Policy, p.222. Washington: Government Printing Office, 2001.

[6] Mayne, J.F. ‘Aldabra – Draft D.O.P.C. Paper’, 12 July 1967. AIR 19/1124. The National Archives.

[7] ‘Mr Healey’s Statement on Aldabra’, 27 November 1967. FCO 46/11. The National Archives.

[8] Stoddart, D. R. ‘The Aldabra Affair’. Biological Conservation 1, no. 1 (1 October 1968): 63–69.

[9] Snoxell, David. ‘Anglo/American Complicity in the Removal of the Inhabitants of the Chagos Islands, 1964–73’. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37, no. 1 (1 March 2009): 132. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086530902757753.

[10] Vine, David.‘War and Forced Migration in the Indian Ocean: The U.S. Military Base at Diego Garcia’. International Migration 42, no. 3 (29 July 2004): 122-123

[11] Kibata, Yoichi. ‘Towards “a New Okinawa” in the Indian Ocean: Diego Garcia and Anglo–American Relations in the 1960s’. In Britain’s Retreat from Empire in East Asia, 1905-1980, edited by Antony Best, 199. Routledge, 2017.

[12] Mavor, L.D. ‘Aldabra: The Bird Strike Problem’, 17 October 1967. AIR 19/1125. The National Archives.

[13] ‘Southern Zone Research Committee – Draft Aldabra Press Statement’, 16 February 1967. FT 3/617. The National Archives.

[14] ‘Record of a Meeting between the Secretary of State for Defence and the President and Other Representatives of the Royal Society’, 22 May 1967. FT 3/617. The National Archives.

[15] Sykes, R. A. ‘British Indian Ocean Territory: Aldabra’, 5 October 1967. FCO 32/114. The National Archives.

[16] ‘Record of a Meeting between the Secretary of State for Defence and the President and Other Representatives of the Royal Society’, 22 May 1967. FT 3/617. The National Archives.

[17] ‘Aldabra: Plan to Develop Airfield Facilities: Memorandum by Secretary of State for Defence’, 18 July 1967. AIR 19/1124. The National Archives.

[18] ‘Note of a Meeting at the Ministry of Defence at 10.30 a.m. on 5th October 1967’, 5 October 1967. FCO 32/114. The National Archives.

[19] ‘Aldabra: The Bird Strike Problem and Possible Remedies’, 16 February 1967. AIR 19/1124. The National Archives; ‘Preliminary Conclusions Following the Recent Survey’, 6 October 1967. FCO 16/228. The National Archives.

[20] Trench, N.C.C. ‘Aldabra’, 27 March 1967. FCO 16/227. The National Archives; ‘Priority Washington to Foreign Office’, 29 March 1967. FCO 32/113. The National Archives.

[21] Moss, E. H. St.G. ‘Aldabra’, 5 April 1967. AIR 19/1124. The National Archives.

[22] Healey, Denis. ‘Aldabra’, 16 August 1967. AIR 19/1125. The National Archives.

[23] Ibid.

[24] ‘Record of Discussion Between the Rt. Hon. Denis Healey, MBE, MP, Secretary of State for Defence and the Hon. Robert S. McNamara, U.S. Secretary of Defense Held 1130, Friday, 29th September, 1967 in Ankara’, 29 September 1967. FCO 32/114; ‘Note of a Meeting Held in the Ministry of Defence at 10.30 a.m. on 11th October, 1967’, 11 October 1967. FCO 16/228. The National Archives.

[25] ‘Note of a Meeting Held by the Secretary of State on Tuesday 17th October’, 18 October 1967. AIR 19/1125. The National Archives.

[26] ‘Note of a Meeting at the Ministry of Defence at 10.30 a.m. on 5th October 1967’, 5 October 1967. FCO 32/114. The National Archives.

[27] Wilford, K. M. ‘Letter from K.M. Wilford to R.A. Sykes’, 26 October 1967. FCO 46/11. The National Archives.

[28] Mayne, J.F. ‘Aldabra’, 4 October 1967. FCO 16/228. The National Archives; Mayne, J.F. ‘Aldabra: Scientific Disagreement and Disagreement’, 9 October 1967. AIR 20/11664. The National Archives; Leitch, G. ‘Aldabra’, n.d. AIR 19/1125. The National Archives.

[29] Berthoud, M. S. ‘Letter from M.S. Berthoud to Mr. Brooke-Turner’, 25 July 1967. FCO 32/113. The National Archives.