An orgy of photographs, diagrams, maps, statistics and essays make Living in the Endless City an elegant and lucid investigation into the best and worst aspects of our increasingly globalised society, finds Amy Thomas.

An orgy of photographs, diagrams, maps, statistics and essays make Living in the Endless City an elegant and lucid investigation into the best and worst aspects of our increasingly globalised society, finds Amy Thomas.

Living in the Endless City. Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic (eds). Phaidon. 2011.

Living in the Endless City. Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic (eds). Phaidon. 2011.

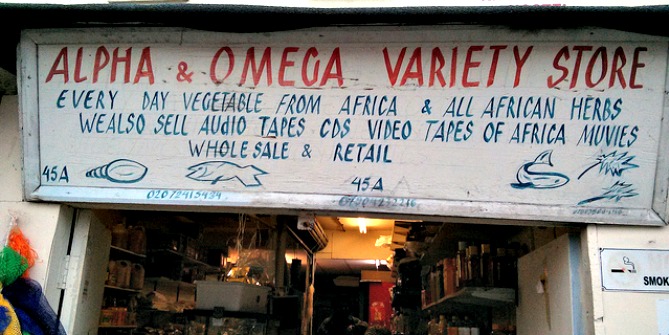

In recent years, the terms ‘globalisation’ and ‘urbanisation’ have become almost synonymous in academic and popular lexicon. With over half of the world’s population living in urban regions that make up just two per cent of the earth’s surface, the efficacy, efficiency and equity of some of the world’s most prominent cities has been a subject of fascination and necessity for researchers, generating polemical discussion from the likes of Mike Davis, Saskia Sassen, Anthony D. King and Jane M. Jacobs, to name a few.

With their increased prominence, cities have come to represent the contradictions of modernity, harbouring the best (technological advancement, job opportunities, a concentration of cultural events, lower carbon footprints, and ethnic diversity) and the worst (gross iniquities in income distribution, crime, cramped living conditions and ghettoization) aspects of an increasingly globalised society. Living in the Endless City, a veritable tome published this year to mark the second and final instalment of the Urban Age Project by the London School of Economics, addresses these extremities. Sponsored by Deutsche Bank’s Alfred Herrhausen Society, the self-proclaimed international ‘think-and-do-tank’, collaborated over five years to produce a comparative study of some of the largest but most diverse cities across the globe, intended to address the problem of accelerated urban growth.

The book takes three cities, Mumbai, Sao Paolo and Istanbul, subjecting them to a rigorous extraction of statistical data, which is then graphically represented and dispersed throughout collections of essays concerning the socio-political and geographical landscape of each case study. In an orgy of full-bleed photographs, bold diagrams, GIS-produced maps and shocking statistics in oversized fonts, the publication falls into the David McCandless (Information is Beautiful) and Edward Tufte (Beautiful Evidence) school of information presentation. This is arguably the most successful part of the book. Elegant and lucid, these visual techniques manage to combine disparate and diverse data sets to clearly address the central problem of the project: is there an overriding trend in urbanization patterns among cities experiencing rapid and unparalleled growth? The answer appears to be no.

In fact, the smallest (but perhaps most interesting) section of the book, entitled ‘Data’, is dedicated to answering this question, comparing the three protagonist cities alongside New York, Shanghai, London, Mexico City, Johannesberg and Berlin. A plethora of beautiful graphs and tables reveal sometimes shocking, but often understandable, comparative statistics. That Mumbai’s CO2 emmissions are approximately 5% of NewYork’s is hardly surprising considering that developed economies have higher energy consumption. However, when you take into account that breathing the air of Mumbai is the equivalent to smoking 50 cigarettes a day, the clarity of such figures becomes hazy. The data on wellbeing and economic equality is equally bewildering. For example, we learn that despite having a GDP nearly thirty times that of Mumbai, New York’s inequality index (where 1 represents perfect inequality in terms of income distribution and 0 represents perfect equality) is 0.5, whilst Mumbai’s is down at 0.35. Furthermore, the results of opinion polls also show that Mumbaikers appear to be the most satisfied with their city, closely followed by London, perhaps disproving the neoliberal mantra that wealth ultimately brings a more contented social body (and, of course, the myth that Britons are notoriously skeptical).

Justin McGuirk’s brilliant interpretive essay addresses the use value and negligence of these statistics. He argues that whilst general trends may be seen to relate poverty to population age and carbon emissions to GDP, cultural and historical variables often skew data sets. In a warning against viewing these statistics in isolation, McGuirk argues that the respective poverty, wealth, development and wellbeing of each city is in fact dependent upon a much wider system that connects all cities. “House prices in London affect the decisions made by affluent Mumbaikers,” he writes, whilst “the National Health Service’s recruiting policies may strip Johannesburg’s hospitals of nurses, and rising crime rates may push its professionals into safer cities.” Ultimately, local specifics aside, “in the global urban ecosystem”, he argues, “one city’s loss may be another’s gain.”

This is a sentiment that is frustratingly rare throughout the entire book. Despite some very interesting and thought provoking pieces of writing on each of the three cities (including Suketu Mehta’s insightful account of the promise and perils of Mumbai and its planning laws, and Hashim Sarkis’s enlightening description of Istanbul’s role as an eastern Mediterranean city), analysis at times seems fragmented and often uncritical of wider international political and economic issues. In much of the scholarship, the overriding criticism lies with governance and policy, at the local and national level, with little, if any, allusion to the role of transnational corporations, foreign policy or historic imperial interventions.

This verve for decentralisation, plurality and site specificity throughout the book (and indeed much contemporary planning theory), coexists with an antipathy towards systemic analysis that results in the acceptance of much broader social and economic iniquities. On the one hand, as Sassen points out in her introductory article, Living in the Endless City is a book about specifics – specific places, specific people, specific histories – and is not seeking to provide an overarching global thesis to account for the materiality of individual cities. However, the disproportionate emphasis on the local as opposed to the global means that the book often feels like it is dodging a great big elephant: the ‘c’ word (yes, capitalism) is scarce, with ‘neoliberal’ only tentatively employed in a couple of articles. If I were being cynical, I might suggest that this light touch may be on account of the book’s sponsor, although I’m sure editorial emphasis is an equally plausible explanation.

Sassen does present some interesting arguments concerning how we might harness the informal and innovative forms of industry that continue to thrive in ‘global cities’. Similarly, Richard Sennett’s intriguing, if at times romantic, comparison of Istanbul to Renaissance Venice, positions these cities as dynamic crossroads at the centre of domestic and international exchange, or as what he calls ‘Hinge Cities’.

Aside from adding to the seemingly endless list of polemical prefixes to applied to cities today (think ‘mega’, ‘world’, ‘entrepot’), Sennett and Sassen’s emphasis points out a secondary issue with this blockbuster publication that is problematic throughout urban research: the preoccupation with the world’s larger cities has led to the neglect of other urban formations that are equally essential to the operations of the domestic and global economy. While the ‘global assembly line’ dispersal of activities is widely acknowledged to be at the root of these larger cities, the components of this supply chain have been largely overlooked, including the multitude smaller urban regions, rural agricultural production areas as well as offshore manufacturing and administrative centres, that are located away from the bright lights of the metropolis. Such spaces, barely mentioned within this book have been a victim of their strategic geographical remoteness and consequently written off the twenty-first century intellectual map, despite the tens of millions of people working within them all over the world. If the overriding theme of the book is to link “people across continents and political systems, ready to learn from and with each to find better solutions for the cities of the future”, surely such spaces cannot be relegated to geographical parentheses.

Despite these criticisms, the book is enjoyable to read, predominantly due to the diversity of its authors (however, with only five female contributors out of a total of thirty-eight, the gender balance is unacceptably biased). The visual aspect of the book is undoubtedly its saving grace, although its encyclopaedic heft does leave me wondering about its intended audience. The large amounts of fairly wordy text combined with its impractical size and high-impact graphics place it on uneasy ground between an academic manual and a Guardian-reader’s coffee table book. Similarly, the scope of the research, swaying from broad statistical surveys to local anecdotal essays, occasionally leaves the reader flailing in the abyss between rigor and romance. In this case, it seems the obsession for big cities and big books has resulted in an uncomfortable marriage of spatial scales.

——————————————————————————————-

Amy Thomas is a PhD student at the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL) in the department of History and Theory. Her research focuses on the impact of financial flows on the built environment, specifically assessing the physical consequences of British Imperial and contemporary offshore capital networks within the City of London. Amy holds an undergraduate degree (MA Hons) from the University of Edinburgh and a Masters from the Bartlett in Architectural History. Amy tweets @UrbanScrivener.

4 Comments