This volume aims to present a systematic, comparative analysis of the many international investigations and reports into the Srebrenica massacre. It brings together analyses from both the external standpoint of academics and the inside perspective of various professionals who participated directly in the enquiries, including police officers, members of parliament, high-ranking civil servants, and other experts. This is a book that not only reminds us of the horrors of what happened in Srebrenica, but also warns us about the mechanics behind writing history and attributing responsibility, writes Laura Bernal-Bermúdez.

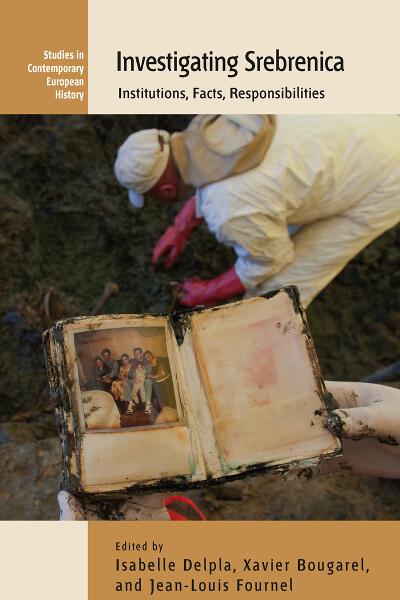

Investigating Srebrenica: Institutions, Facts, Responsibilities. Isabelle Delpla, Xavier Bougarel and Jean-Louis Fournel (eds.). Berghahn Books. 2012.

Investigating Srebrenica: Institutions, Facts, Responsibilities. Isabelle Delpla, Xavier Bougarel and Jean-Louis Fournel (eds.). Berghahn Books. 2012.

The Srebrenica massacre of July 1995 marked the annals of history. Not only were thousands of people massacred but more disturbingly, they were killed in a UN ‘safe area’, while the UN and the international community stood by and watched. Following the deaths of over 8,000 Bosniac men – carried out by the Bosnian Serb Army, led by General Ratko Mladić, who is now on trial at The Hague – debates over issues of responsibility and protection have been prominent. The questions that remain today are: how are the annals of history written? And how and what type of responsibility is assigned? Investigating Srebrenica: Institutions, Facts, Responsibilities gives us an analysis of the different ways in which actors involved in the Srebrenica events have handled the issue of ‘truth’ and responsibility.

In the introductory chapter Isabelle Delpla, Xavier Bougarel and Jean-Louis Fournel provide an analytical framework for approaching the three-fold process of writing history, assigning responsibility, and creating a public debate around foreign policy. The authors then provide a comparative analysis of the major reports and investigations which have been produced on Srebrenica, including the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) investigation, a UN report, the French National Assembly Fact-Finding Mission, NIOD’s report, the Dutch Parliament report and the Republika Srpska parliamentary debate and report. The main contribution of this work is clearly to be found in this comparative analysis, which allows the reader to assess not only the results but also the rationales behind the production of ‘truth’ and the attribution of responsibility. As the authors dissect each report, they expose how each came into being and the way in which national and international institutions are charged with confronting their own responsibility while writing history. It is an interesting exercise that challenges the cloak of objectivity used by those who claim to be ‘writing history’ and assigning responsibility.

The body of the book is composed of seven chapters, each assigned to one of the reports mentioned above. The analysis is greatly enriched by the authors’ professional experience as some of them, including Jean-René Ruez, Pierre Brana, Michele Picard and Asta M. Zinbo, participated in writing the history of Srebrenica.

Chapter 1 includes Isabelle Delpla’s interview with Jean-René Ruez on his work in the ICTY. He led the Tribunals’ investigations into the Srebrenica massacre, and was able to provide invaluable insights into the way the investigation was framed, ‘judicial truth’ was written, and criminal responsibility was assigned. Ruez discusses how the investigation did not cover some of the most important political and social context, and highlights the impact this had on the Tribunal’s narrative of the event. The investigation left out the causes of the fall of Srebrenica; it also only examined situations where a large number of victims had been assassinated and focused on the participation of military leaders. It was centred on criminal responsibility, leaving out any consideration of moral or political responsibility. In the interview, Ruez illustrates how the construction of knowledge in the ICTY was restricted to individual responsibility and the need to have solid evidence to present charges. This meant that the production of knowledge was not only a matter of certainty but what was written in history depended on what the prosecutor would be able to prove in court.

Finishing this first chapter, the reader then moves on in search of the way in which other reports might fill the gaps left by the ‘judicial truth’ or somehow present other sides of the prism. However, readers may be struck by how these gaps are not easily filled, considering that those who were in control of writing the history of the event were also, simultaneously, being confronted with their own responsibilities in the terrible fate of Srebrenica. Chris Klep and Pieter Lagrou present the most compelling case in their chapters on the Dutch Parliamentary and NIOD reports on Srebrenica. The Netherlands had been involved in the fall of the enclave, sending troops as part of the UNPROFOR mission. The DUTCHBAT battalion left Srebrenica, leaving the population behind. After they left, there were rumours in the media accusing the soldiers and authorities in The Hague of not doing everything in their power to prevent the tragedy. According to Klep and Lagrou, in the Netherlands, the process of writing history was used to wipe clean any responsibility for the events in Srebrenica. Klep argues that the reports even tried to portray the Dutch as victims of international realpolitik and the weakness of the UN. Given that narrating the truth implies self-scrutiny and attributing responsibility to those who were still in power, these accusations were met with political pragmatism and even escapism. There were high moral and political stakes that shaped the way the ‘truth’ was told.

There is a cross-cutting issue in the chapters, which is then particularly addressed by Delpla in the concluding chapter, around the question of whether the search for intelligibility through the writing of history and construction of knowledge could eventually relieve all parties of all responsibility (‘if everyone is responsible, no one is’). This is a very interesting question to test with other case studies such as the recent report issued by the Centre of Historic Memory in Colombia, narrating an internal armed conflict that has been ongoing for more than 50 years.

This is a book that not only reminds us of the horrors of what happened in Srebrenica, but also warns us about the mechanics behind writing history and attributing responsibility. It provides us with a framework to analyse the hundreds of reports that are being written around the world in an effort to come to terms with past atrocities. Whether readers are interested in international relations, law, human rights, history or sociology, this book will have something to bear in the way in which we all approach the issue of understanding rationales behind knowledge. This work fills a gap in the current literature on the main reports and investigations of Srebrenica, since these had not been, until now, the objects of comparative analysis.

—————————————————

Laura Bernal-Bermúdez is a lawyer from Colombia with experience in human rights, administrative and constitutional law. Currently she is a research assistant in the Department of Sociology at the University of Oxford, working as a part of a team to develop a database of company human rights abuses around the world. She has worked for the state, in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; for companies, in a commercial law firm; and with civil society, in Redress and Oxfam GB. She finished her MSc. Human Rights at the LSE and is due to begin the DPhil programme in Sociology of the University of Oxford. Read more reviews by Laura.

2 Comments