This book considers South Sudan’s modern history as a contested region, and assesses the political, social and security dynamics that will shape its immediate future as Africa s newest independent state. This is an essential piece of reading for any scholars, policymakers and practitioners with an interest in the Horn of Africa, writes Ann Fitz-Gerald. The work is exceptionally well-researched and builds effectively and comprehensively on existing literature of scholars such as Douglas H. Johnston, Robert O. Collins and Martin Daly.

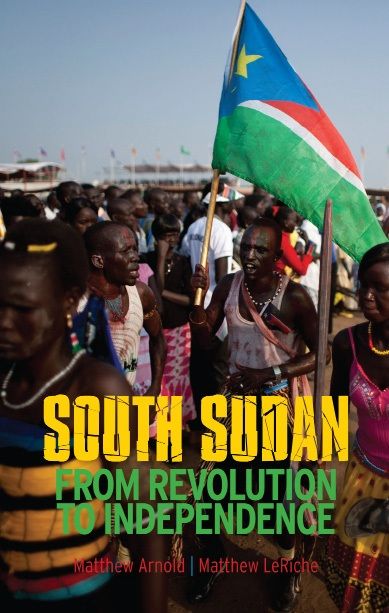

South Sudan: From Revolution to Independence. Matthew Le Riche and Matthew Arnold. Hurst & Co. July 2012.

South Sudan: From Revolution to Independence. Matthew Le Riche and Matthew Arnold. Hurst & Co. July 2012.

Matthew Le Riche and Matthew Arnold are two young political scientists who have written a persuasive account of both of Sudan’s civil wars, events leading up to the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, and the real issues which impact the future viability of the world’s newest nation. The privileged access that the authors have gained as a result of their time spent in South Sudan, and the respect both earned from Government officials, former fighters, international officials and – most importantly – citizens of South Sudan – enriches this book with knowledge that cannot be found in other seminal pieces of literature on conflicts in the region.

The book undertakes to tell the story of the transformation of Southern Sudan as a region into South Sudan as a state. The book revolves around the following three questions: 1) Why did a first civil war aimed at secession result in a form of semi-autonomy, while a second civil war fought in the name of national revolution ended in secession? 2) Why did an entrenched dictatorship in Khartoum, which had shown itself to be so ruthless to opposition to rebellion for so long, finally take the drastic step in allowing a peaceful referendum on secession? And, 3) how is a poverty-stricken, land-locked state with strong internal tensions and a heavy reliance on diminishing oil revenue going to survive its own independence? (p.2) In answering these three questions, the authors acknowledge the difficulty of the task they set out to achieve; that is, to examine a series of key contradictions in light of the unresolved root causes of conflict and anxiety that still exist today.

The first half of the book provides an overview of the region, emphasizing the Second Civil War and the CPA Process. One central theme which runs throughout this first half is the role that John Garang played in creating both divides and reunifications within the SPLA, the national revolutionary movement. The dynamics presented in this half of the book are both helpful and illuminating in understanding present day fall-outs between senior figures such as President Salva Kiir and former Vice-President Riek Machar; between the Government and former catechist and SPLA-affiliate David Yau-Yau; and a range of other lingering and unresolved rifts, the resolution of which was not catered for by the CPA.

The authors also do an excellent job of enlightening readers on the impact that John Garang’s death had on the direction of the CPA; and the perceived focus of future peace agreements more generally. The authors state ‘with Garang gone, the interpretation of the strategic nature of the CPA changed’ and that ‘during the six years, neither side implemented fully the details of the Agreement.’ This point underscores not only the enormity of the detail of the CPA (the consolidation of six separate agreements) – but also the importance of Garang’s custodian and champion role. Without his leadership, ‘objectives became known as ridding the south of the north and not establishing a southern identity.’ Garang’s strategic and multi-stakeholder approach, which demonstrated the need for the South to recognize the Northern agenda whilst catering for their own needs, was vastly complex and, arguably, a near-impossible agenda that no other southern leader had the credibility or approach to manage. Irrespective of the public mood towards southern independence, the book also underscores Garang’s ongoing conciliatory efforts to ‘make unity attractive’. As a result, and since his death, it is hardly surprising that a number of major provisions in the CPA – such as the referendum on Abyei – have yet to be implemented.

Towards the end of the first half, the book makes some insightful points relating to what improved conditions for a negotiated settlement between the north and the south. The first point was that war was still hindering oil wealth. Whereas the south had existed and persevered under conditions of deprived oil wealth for years, it was a situation that could no longer be sustained by the north, particularly in the wake of diminishing global exports and increases in food prices. The next two points, which are interlinked, relate to IGAD’s role in brokering the CPA and the former Kenyan President Arap Moi’s encouragement toward Bashir to remain engaged in the peace talks (p.108). This issue is important for two reasons. The role of IGAD helps reminds readers of the UN’s minimal involvement in pre-CPA Sudan (with the exception of the Darfur intervention) and, despite the relatively weak secretariat capacity of IGAD, the strength of certain key Heads of State in bringing the Sudanese parties back to the table, and in securing the CPA. Perhaps one point that the authors could have made bolder in this section was the role of Ethiopia – and particularly of the late Prime Minister Meles – in keeping both sides involved in the peace talks. This unique relationship that Ethiopia had with both sides, and the challenging approach Meles took to maintaining a relationship with Khartoum in the North; whilst supporting the common concept of ‘liberation’ and ‘struggle against oppression’ in the south – was significant. This unique relationship also facilitated the deployment of the Ethiopia-commanded/UN mandated troops to Abyei, as well as Ethiopia playing host to most of the post-referendum peace talks on outstanding issue

The last half of the book describes and analyses the founding of the new state, outlining its structures of governance and the political, security and social dynamics defining its immediate future. This latter half of the book exposes challenges and cleavages that underscore the non-inclusive nature of the CPA. As stated by the authors, “…much of [the CPA process] was resolved between small negotiating groups, appointed by John Garang and made up of his preferred intellectuals” (p.144). Up until now, available literature offers little elaboration of this issue compared with the detail offered by Arnold and LeRiche, particularly in terms of the way the lack of social cohesion in the country is impacting on current Government policy and programme implementation. To date, very few analysts have questioned the apparent lack of alignment between current international approaches to peacebuilding and the desperate need for reconciliation across communities, establishing a national dialogue, and taking forward the policies of a more united vs splintered nation.

In summary, this is an essential piece of reading for any scholars, policymakers and practitioners with an interest in the Horn of Africa. The work is exceptionally well-researched and builds effectively and comprehensively on existing literature of scholars such as Douglas H. Johnston, Robert O. Collins and Martin Daly. The concluding issues and questions raised at the end of the book are both deep and thought-provoking. These well-informed issues and questions will no doubt shape and inform both the academic and policy debate on South Sudan in the years to come.

———————————————-

Ann Fitz-Gerald is Professor of Security Sector Management at Department of Management and Security at Cranfield University. She has published on peacekeeping, conflict, and humanitarian organisation management. Read more reviews by Ann.