In Britishness, Popular Music and National Identity, Irene Morra offers a major exploration of the social and cultural importance of popular music to contemporary celebrations of Britishness. This book represents a valuable contribution to the corpus of academic literature on both popular music and national identity, and would be a welcome addition to the reading lists of scholars and students of History, Music and English Literature, as well as Cultural and Media Studies, writes Ruth Adams.

In Britishness, Popular Music and National Identity, Irene Morra offers a major exploration of the social and cultural importance of popular music to contemporary celebrations of Britishness. This book represents a valuable contribution to the corpus of academic literature on both popular music and national identity, and would be a welcome addition to the reading lists of scholars and students of History, Music and English Literature, as well as Cultural and Media Studies, writes Ruth Adams.

Britishness, Popular Music and National Identity. Irene Morra. Routledge. November 2013.

Britishness, Popular Music and National Identity. Irene Morra. Routledge. November 2013.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

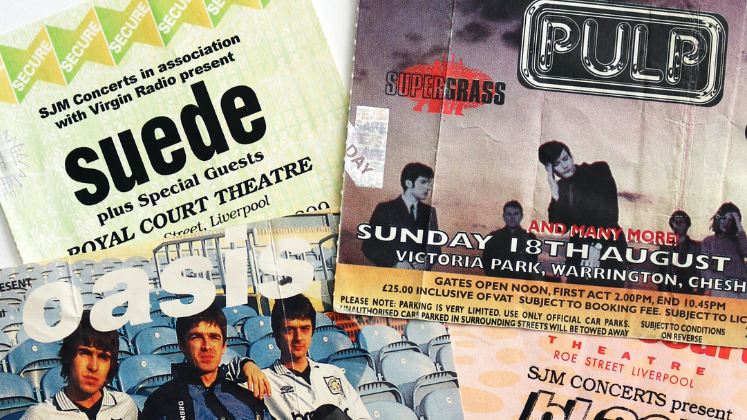

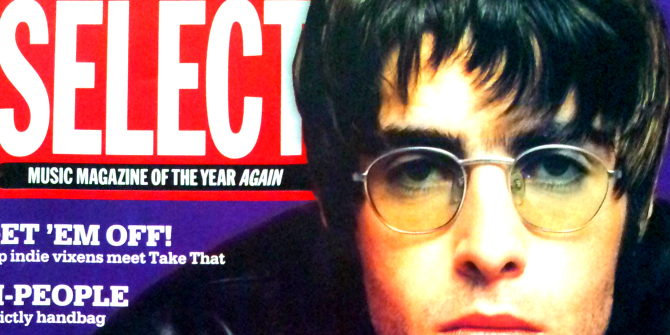

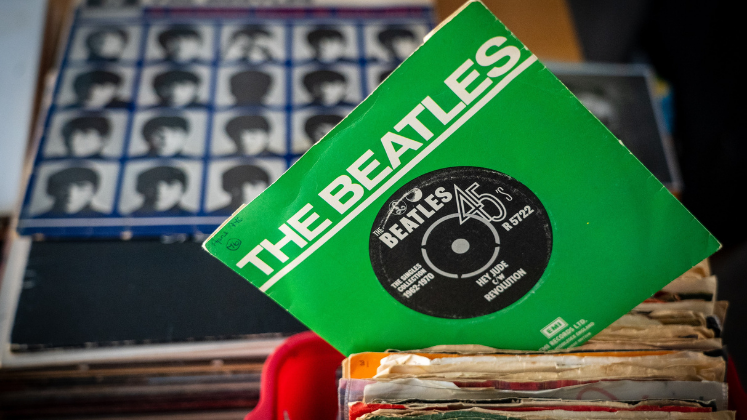

The opening and closing ceremonies of the London 2012 Olympics were essentially pageants of British pop, tracing a national cultural history from the Beatles to Dizzee Rascal’s ‘Bonkers’. This is a key piece of evidence in Irene Morra’s argument that popular music is now widely regarded as the most important signifier of British national identity. Pop is valued as an authentic articulation of the lives and feelings of ordinary people, of a common heritage, it speaks of a ‘history of progressive expression and innovation’; consequently, it is a source of patriotic pride, bolstered by its importance in export markets and the role it plays in globalised demonstrations of ‘soft power’. In the 1990s, ‘Britpop’ was hailed as a ‘British Invasion’ echoing the world-conquering antics of the Beatles in the 1960s, and groups as diverse as the Spice Girls and Oasis adorned themselves with the Union Flag. Coming to power in the midst of this renaissance, Tony Blair declared that ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll is not just an important part of our culture, it’s an important part of our way of life.’

Despite becoming common currency, Morra argues that the national(ist) aspects of pop music have been nonetheless largely overlooked in academic writing. She attributes this in part to a long-held belief that Britain had contributed little to the canon of classical music; compared to English Literature, where a dominance and significance could be more confidently asserted. Scholarly analyses of popular music have tended to eschew the nation in favour of the local and the global. This book addresses this omission via an analysis of ‘two dominant, conflicting constructions around popular music: music as the voice of an indigenous English ‘folk,’ and music as the voice of a re-emergent British Empire.’

Morra’s argument that popular music is now accepted as the authentic ‘folk’ music of modern Britain is a strong and well-crafted one. It is set against the largely vain attempts by folk revivalists to find a mainstream audience for ‘traditional’ folk song, which appears to the majority not as an ‘organic’ element of the national cultural landscape, but as artificial and anachronistic. Folk music lacks the perceived vernacular ‘authenticity’ of pop, which can make a more genuine claim to be ‘of the people’. The famous Paul McCartney quote that he knew he had made it when he heard the milkman whistling From Me To You seems apt here.

Image Credit: Photo by Bob Coyne on Unsplash

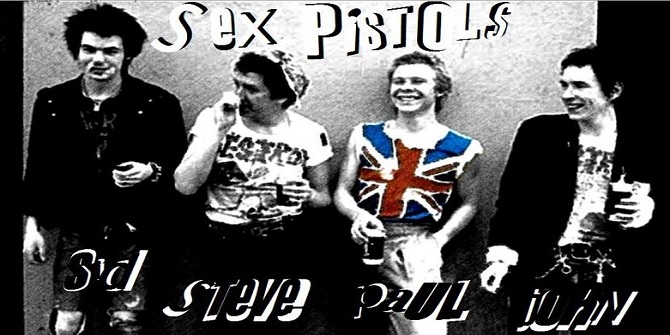

The British pop music scene that emerged from the early 1960s represented a sloughing off of the constraints of the traditionalist values of a prudish and class-ridden society, the end of post-war austerity and post-imperial decline. Youth culture was liberating, modern and progressive, and shifted the means of cultural production into the hands of its consumers. However, so influential was this period that what once was an exemplar of irreverent innovation has, Morra asserts, hardened into a restrictive template in which the popular canon ‘remains characterized by an assumption of the continuing, necessary dominance of the four- or five-man guitar group’, and every new act that looks set to enjoy popular success is assessed and understood in relation to a small number of canonical groups, slotted into a timeline which suggests a linear and ‘continuous mode of national expression’. By way of illustration, Morra quotes a review of the Artic Monkeys’ debut album in the NME:

Essentially this is a stripped-down, punk rock record with every touchstone of Great British Music covered: The Britishness of The Kinks, the melodic nous of The Beatles, the sneer of Sex Pistols, the wit of The Smiths, the groove of the Stone Roses, the anthems of Oasis, the clatter of The Libertines…

But alongside this the perception that popular music ‘must rebel against oppressive classes and resist dominant structures’ (or at least appear to) also persists. Mainstream success of the wrong sort risks fatally compromising its ‘authenticity’, although of course the recuperation of pop into a discourse of national culture is itself a form of institutionalisation. ‘Authentic’ pop is born amongst the marginalised and alienated. Working class origins confer legitimacy, and the perennial marginalisation, geographical and social of the apparently ‘universally disenfranchised’ North of England can be usefully deployed as pop provenance.

However, as Morra demonstrates, the parameters defining the acceptable outsider are extremely narrow. The chapter on ‘Women and Song’ succeeds in highlighting the patriarchal biases of the music industry and its audiences; however, given how widespread this tendency is, the extent to which it illuminates the specifics of the British case is questionable. The chapter on ‘Race and Indigeneity’ better addresses the peculiarities of British race relations and how these have been played out in popular music. It argues that despite – or perhaps even because of – the best efforts of initiatives such as Rock Against Racism, the British popular music tradition is one which ‘continues to originate from (and assume) a predominantly white, indigenous demographic’. Black music might be a significant and consistent influence on British pop, but it has been whitened in the process of translation. Black artists are ghettoised under the heading of ‘urban’, and censured if they attempt to step beyond the accepted boundaries of the genre. The mainstream music industry and media lack, it would seem, either the imagination or the inclination to see BME artists as anything other than convenient stereotypes.

This perhaps points to one of the limitations of the book, however. While it is of course important to subject dominant discourses to critical scrutiny, Morra’s decision to focus exclusively on the mainstream music press and news media risks merely reinforcing her thesis and replicating the exclusion of divergent or resistant voices. The hegemonic grip of influential publications such as the NME was neither total, nor permanent. In a digital age they now compete with a proliferation of websites, blogs, forums, and social media devoted to music criticism, which articulate a wider range of points of view and, in the process, diversify cultural agency beyond a clique of white, male, rock-oriented journalists.

That said, this is an informative and often engaging read, which covers a broad sweep of the history of British popular music with an evident enthusiasm for its subject. It represents a valuable contribution to the corpus of academic literature on both popular music and national identity, and would be a welcome addition to the reading lists of scholars and students of History, Music and English Literature, as well as Cultural and Media Studies.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

2 Comments