In 1996 and The End of History, journalist and author David Stubbs examines a year – 1996 – that marked the pinnacle of a decade, not just in politics but across music, entertainment and sport. Tying together the political and cultural landscapes of mid-nineties Britain, this is a valuable addition to the current critical reassessment of a period that seemed to promise sunnier times ahead. But, asks Stephen Lee Naish, could it ever last?

1996 and the End of History. David Stubbs. Repeater Books. 2016.

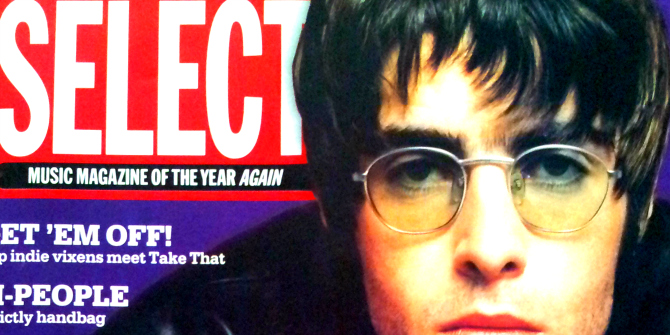

I was born in 1996, not literally – that happened in 1981 – but metaphorically. As I approached the age of sixteen, and the cultural world began to coalesce, I became a draft version of the person I am today. This was my final year of formal education; I sat my GCSEs with little hope; and as the summer ended I would learn that I had failed most of them. This barely registered as a disappointment as, flush with money from my first full-time job, I ordered a fake ID from the back of Loaded magazine and hit the pubs and clubs with likeminded mates. Furthering education, or in my case restarting it, seemed utterly irrelevant. What did I, or anyone else for that matter, need with a proper education? Intelligence could be found by proxy on a Manic Street Preachers record. Aspiration to be anything else could be found in the music and lifestyle magazines of the era. Publications like NME, Melody Maker, Select and FHM promoted images of waifish rock stars, scantily clad beautiful women, affordable designer polo shirts, the latest gadgets and, despite my lack of interest, an inclusive football culture. The ill-defined ideals of ‘Cool Britannia’ were everywhere and our British chests thumped with pride, we embraced tolerance and looked towards a very bright future.

I was born in 1996, not literally – that happened in 1981 – but metaphorically. As I approached the age of sixteen, and the cultural world began to coalesce, I became a draft version of the person I am today. This was my final year of formal education; I sat my GCSEs with little hope; and as the summer ended I would learn that I had failed most of them. This barely registered as a disappointment as, flush with money from my first full-time job, I ordered a fake ID from the back of Loaded magazine and hit the pubs and clubs with likeminded mates. Furthering education, or in my case restarting it, seemed utterly irrelevant. What did I, or anyone else for that matter, need with a proper education? Intelligence could be found by proxy on a Manic Street Preachers record. Aspiration to be anything else could be found in the music and lifestyle magazines of the era. Publications like NME, Melody Maker, Select and FHM promoted images of waifish rock stars, scantily clad beautiful women, affordable designer polo shirts, the latest gadgets and, despite my lack of interest, an inclusive football culture. The ill-defined ideals of ‘Cool Britannia’ were everywhere and our British chests thumped with pride, we embraced tolerance and looked towards a very bright future.

Writer and journalist David Stubbs’s latest book, 1996 and the End of History, is an accurate recap of the year’s heady optimism. By tying the political and cultural landscapes of the mid-nineties together, Stubbs offers an account that certainly, as one who lived in those times, dips into nostalgia but doesn’t cheapen the era, and in fact points to 1996 as a kind of doppelganger for other modern revolutionary years, like 1966 (Swinging London), 1969 (Summer of Love), and 1977 (the emergence of punk).

The book begins with New Labour leader Tony Blair who, for good or ill, was a defining figure of the mid-to-late-nineties and beyond. As the British Conservatives saw out their final moments in power after sixteen years of hard rule, Blair was basically PM-in-waiting. Stubbs peels back Blair’s popularity using Peter Mandelson and Roger Liddle’s 1996 manifesto, The Blair Revolution: Can New Labour Deliver?, to uncover Blair’s policies as not the ‘revolution’ that was being touted, but just a continuation of Thatcherism. Of course, in hindsight this is all obvious. Yet, at the time, one was easily led into believing New Labour was an embodiment of the sunny disposition of the era, as if our very mindset had created them to rule over us. When set against the grey mulch of then Prime Minister John Major and the rest of the Conservatives, Blair’s arrival was a second coming, and if you believed it, it would last a lifetime.

Image Credit: (Andy Bullock CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Andy Bullock CC BY 2.0)

Even though the main protagonists, Oasis, Blur and Pulp, were absent from the charts, Britpop was also at its peak in 1996. Despite not releasing an album that year, Oasis were a dominant force with massive sold-out shows at Knebworth and daily tabloid appearances from the Gallagher brothers. Off the back of the perky The Great Escape (1995), Blur would return in 1997 with the more lo-fi Blur. Pulp, a band that had been plugging away since the early 1980s, suddenly had their moment with class anthem, ‘Common People’, but a brooding, darker version of the band would emerge in 1998 with This is Hardcore. Stubbs nonetheless shows that an undercurrent of differing musical styles was also flowing freely beneath the piss-foam indie jangle of Britpop coattail surfers like Sleeper and Menswear, identifying a number of other worthy bands and artists such as Afghan Whigs, Stereolab, Aaliyah, LTJ Bukem, DJ Shadow and Tricky, whose music offered innovation and an alternative to Britpop.

Another alternative to boorish, laddish Britpop was the uncouth feminist pop of The Spice Girls, who emerged in the summer of 1996 with the song ‘Wannabe’, a brash, feisty anthem of female solidarity. Stubbs gives them due acceptance as a powerful and influential popular force that tied in with the emerging ladette culture where women could be as outspoken as men, and also drink them under the table. Yet Stubbs also comments on the failures of their ‘Girl Power’ manifesto. What should have been a revolution, or at the very least a re-evaluation of popular feminist discourse, was only a dusting of the mantle. The group’s proclamation that Maggie Thatcher was the first Spice Girl called into question their radical brand. In the eyes of The Spice Girls, all feminist battles had been fought and won, and their very existence was testament to this. Still, with the male dominance of pop music and guitar bands springing up daily, The Spice Girls, for a short while, offered some much-needed pop glamour.

The chapter on music is broad and revealing, yet still a question remains: why decline to mention the triumphs of bands such as Ash, The Bluetones, Placebo and The Lightning Seeds? Ash’s 1977 was an indie-punk victory that saw the band score hit singles throughout the year and grace the covers of Smash Hits, NME and Kerrang!. The Bluetones debut, Expecting to Fly, contained two of the best singles of the year: ‘Slight Return’ and ‘Cut Some Rug’. Placebo offered a much needed alternative to the laddish antics of Britpop, signified by the androgyny of singer, Brian Molko, and songs of depravity like ‘Nancy Boy’ and ‘Bruise Pristine’. Whilst The Lightning Seeds do get credit for ‘Three Lions’, the England Euro ‘96 theme, Dizzy Heights goes unmentioned along with the pop genius of the group’s creative force, Ian Broudie. Of course, this all falls into personal interpretation of the times, but these bands felt massive, and not for the first time have been sadly disregarded.

Speaking of music, it is both fitting that Stubbs gives Oasis a full chapter that outlines their utter dominance of the ‘90s, yet oddly hollow considering the music actually being released in 1996. Whilst they were still Britain’s biggest band, it was clear Oasis were on a slide. Drugs, booze, egotism, sheer exhaustion and Caribbean holidays with Johnny Depp all took their toll as well as living up to the initial hype of following the Beatles, when, as Stubbs points out, they had more in common with ‘70s stompers, Slade. In 1997, Oasis would release Be Here Now, and whilst it received acclaim at the time, most of us would have preferred to have been anywhere else after a few listens. Be Here Now was an immense disappointment, but the band’s slip into total irrelevance was already underway.

Stubbs also ventures into the comedy of the mid-nineties, which from memory seemed like dire times. Laddish entertainment shows like TFI Friday were dominant. The show’s host, Chris Evans, larked around the studio getting a laugh by humiliating anyone in his proximity. Yet Stubbs makes an excellent case for shows that were much loved at the time. Irish parochial comedy Father Ted receives a brilliant summarising, whilst sketch comedy The Fast Show is given credence for its wacky skits and lasting catchphrases. Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer’s outstanding and surrealist comedy quiz show, Shooting Stars, baffles most, yet its format has been widely replicated. 1990s comedy was predominantly apolitical, to which Stubbs concludes that it simply matched the cheery mindset of the era. The political commentary that was so blunt in 1980s comedy was mostly absent in the nineties because politics – or at least the kind that we thought needed to be rallied against – was largely missing from the British consciousness during this time.

Even someone as adverse to football as myself felt excited by England’s 1996 European Championship prospects; it is to here and other prominent sporting events like Frank Bruno’s fight with ‘Iron’ Mike Tyson that Stubbs also turns. England’s campaign was soundtracked by The Lightning Seeds’s aforementioned anthem ‘Three Lions’, also featuring comedians David Baddiel and Frank Skinner, and went on to define the glorious – and from what I recall, eternally sunny – summer of 1996. As the England team pulled themselves together, it really did feel like football was ‘coming home’, and if it had, the optimism of the year might have actually blown our heads clean off. However, I can still clearly recall defender Gareth Southgate’s look of disbelief as his penalty was saved, thus ousting England and ending a dream that seemed almost certain to come true. This should have been our reality check. Not everything can be this good.

Of course 1996 could never last. Faith was placed in all the wrong entities. 1997 and the decade’s subsequent years could never hope to match it. How did we ever let the triumphalism of 1996 get away? As Stubbs concludes, it was never ours for the taking. It was, and always is, a distraction. There was never any real revolution in politics or music or feminism or culture: it was only a continuation of the end of history, an ending that in the neoliberal mindset can never truly come. Alongside John Harris’s The Last Party, John Robb’s The Nineties and Rhian E. Jones’s Clampdown – all books that outline the ‘90s from various perspectives of politics, culture and gender – 1996 and the End of History is a quality addition to the critical reassessment of ‘90s Britain. Like the above, Stubbs revels in the idealism and optimism of the time, but concludes that, ultimately, it was a fool’s errand.

Stephen Lee Naish‘s writing explores film, politics, and popular culture. His essays have appeared in numerous journals and periodicals. He is the author of U.ESS.AY: Politics and Humanity in American Film (Zero Books) and Create or Die: Essays on the Artistry of Dennis Hopper (Amsterdam University Press), and the forthcoming Deconstructing Dirty Dancing (Zero Books). He lives in Kingston, Ontario with his wife Jamie and their son Hayden. Read more by Stephen Lee Naish.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.