In Going Viral, Karine Nahon and Jeff Hemsley look to uncover the factors that make tweets, videos, and news stories go viral online. They analyze the characteristics of networks that shape virality, including the crucial role of gatekeepers who control the flow of information and connect networks to one another. This concise and insightful book targets a niche topic in the studies of digital media that is becoming increasingly relevant to the public. It considers many questions and successfully accomplishes what it sets out to do. Students of media, digital worlds, and information studies will not be disappointed, finds Nikki Soo.

Going Viral. Karine Nahon and Jeff Hemsley. Polity Press. October 2013.

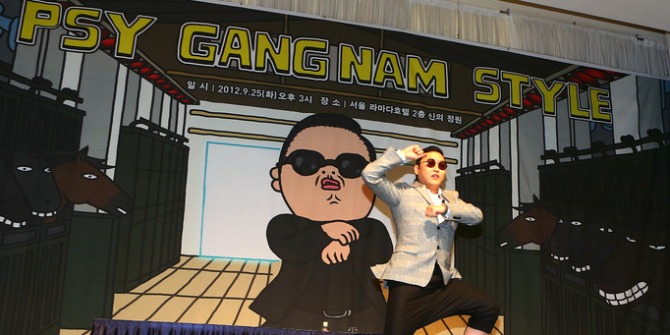

Do the names Susan Boyle, Alexandra Wallace, and PSY ring a bell? Each of these now household names was at one time leading a relatively anonymous life in their homes in Scotland, America, and South Korea respectively, but due to the viral popularity of YouTube videos in which they feature their lives have changed forever and they are known to millions around the world.

For those in need of a refresher, the video of Boyle singing “I Dreamed a Dream” from Les Misérables on Britain’s Got Talent in 2009 reached an audience of almost 100 million people within 10 days. Former UCLA student Wallace’s racist video rant about Asian students in the university library was shared by tens of thousands of people of Facebook within three days of posting, and PSY’s Gangnam Style music video critiquing South Korean materialism has achieved a staggering 2 billion views since being released in July 2012. In all three examples, virality has ensured that many millions – and now even billions – of people are aware of these videos.

Although there is a lot of interest in the viral nature of online articles and videos today, viral marketing has been employed to increase the sales of products and awareness of brands since the 1990s. The term was first coined by Steve Jurvetson in 1997, after he observed how the impressive growth of email provider Hotmail seemed to be down to the rapid spread of word-of-mouth recommendations. Academic literature has recognised the power of virality, but research has often focused on other factors rather than virality itself, such as Kevin Wallsten’s work on the role of blogs in stimulating the popularity of videos during the 2008 US Presidential Elections. As such, virality is not a particularly novel concept, but the advent of the internet and digital media has made it much easier for a product to perpetrate popular culture or public awareness (remember that KONY video?).

In Going Viral, Karine Nahon and Jeff Hemsley – both at the University of Washington’s Information School – embark on the challenging task of investigating internet virality, helping us to understand what virality is and how it works, how we might go about measuring virality, and what benchmarks are required for something to become viral. Written in an accessible style and with key examples, graphs, and tables to illustrate their theories, this book is highly recommended for students, researchers, policymakers as well as general readers interested in learning more about this hot topic.

Virality is an emergent feature of society that has resulted from interconnected social media usage that has – for many – become embedded into everyday life, generating what the authors term a “dynamic social infrastructure”. Beginning the book with a vignette of Rosa Parks and her refusal to adhere to the segregation law in 1955, Nahon and Hemsley demonstrate how the concept of viral information is not novel. Rather, it is the nature of virality that has metamorphosed. Unlike other scholars in the field, the authors do not consider virality to be an absolute game changer that will empower the masses, but instead they assert that it can both reproduce and transform existing social norms and institutions.

The authors have organised the book into seven chapters, aiming to explore the concept of virality in depth and to make its inter-workings more transparent, accessible, and understandable to a broad audience. Chapter 2 begins by first defining the notion of virality before identifying and explaining key aspects of the term, including speed and reach. Establishing it as “a social information flow process where many people simultaneously forward a specific information item, over a short period of time, within their social networks, and where the message spreads beyond their own networks to different, often distant networks, resulting in a sharp acceleration in the number of people who are exposed to the message” (p. 16), the authors are also careful to distinguish what it isn’t. A series of graphs throughout the chapter demonstrate how social media and mass media interact with each other, also depicting the slow-fast-slow signature that is unique to the lifecycle of a viral event.

Chapters 3, 4, and 5 dissect and analyse factors that are behind a viral event. Chapter 3 focuses on the top-down forces behind the viral process, more specifically what the authors term ‘network gatekeepers’. Examples include the Occupy Movement and the Arab Spring. Contending that network gatekeepers have an immense impact on information flows, they are also quick to point out that this position of power is never permanent. This is especially so in an economy where attention is considered a scarce resource.

The focal point is turned towards the masses in Chapter 4, where the bottom-up process is reviewed and evaluated. Highlighting the role of personal influence and interest networks, the power of remarkable amateur content is investigated. It is found that tapping into emotions such as humour, surprise, and novelty assists media content in being selected by users. Chapter 5 integrates these two perspectives by focusing on the structural networks in which the top-down and bottom-up processes are embedded, further strengthening the authors’ compelling arguments on how virality occurs.

Nahon and Hemsley conclude their investigation of virality in Chapter 7, aptly titled “Afterlife”. This chapter contemplates the ‘decay’ of a viral event, a stage of its life cycle that is not often considered. Labelling the process inevitable, they provide an answer drawn from research by psychologist Warren Thompson on attentional economics, citing that our limited attention spans require us to stop paying attention to something older to devote attention to something new. Ultimately, a viral event relies on social interactions and has evolved along with new technologies.

This concise and insightful book targets a niche topic in the studies of digital media that is becoming increasingly relevant to the public. It considers many questions and successfully accomplishes what it sets out to do. Students of media, digital worlds, and information will not be disappointed.

————————————————

Nikki Soo is a PhD Candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her research interests are political communication, the use of digital media in campaigning and democratisation. She holds an MA in Public Policy from King’s College London, and an MSc in New Political Communication from Royal Holloway. Follow her on Twitter @sniksw. Read more reviews by Nikki.

11 Comments