In 2013, out of 7,776 female state legislators serving across the USA, 364 are women of colour; of these 239 are African American women. Linking personal narratives to political behavior, Nadia E. Brown elicits the feminist life histories of African American women legislators to understand how their experiences with racism and sexism have influenced their legislative decision-making and policy preferences. Muireann O’Dwyer is enthusiastic about the impact of Brown’s work.

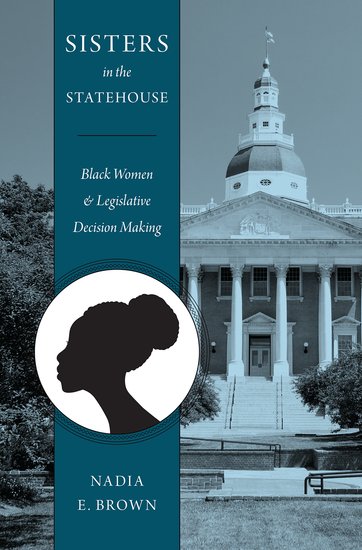

Sisters in the Statehouse: Black Women and Legislative Decision Making. Nadia E. Brown. Oxford University Press. 2014.

Sisters in the Statehouse: Black Women and Legislative Decision Making. Nadia E. Brown. Oxford University Press. 2014.

In Sisters in the Statehouse: Black Women and Legislative Decision Making Nadia E. Brown has delivered an outstanding example of applying an intersectional approach to a traditional question of political science. Brown, an Assistant Professor at Purdue University, has written a book which will be of great interest to scholars of political representation, but perhaps even more significantly, she has delivered an answer to the enduring question of how exactly intersectionality can be brought to bear on the empirical questions of social science.

Intersectionality, the concept that the multiple identities and situations of people can combine to shape their experience in a mutually constitutive way, is one of the key contributions of modern feminist theory. Beginning with a critique of the exclusion of the voices and experiences of Black women from mainstream White feminism, this approach argues that, for example, race and gender interact to create different experiences of oppression, and not simply an additive one. While there has been extensive theoretical debate and conceptual development surrounding intersectionality, there has also been growing concern at the difficulty of translating this theory into a methodology.

Through seven chapters, Brown applies the intersectional approach to her study of the legislative behaviour of Black women legislators in the Maryland State legislature in the United States. She combines the methods of participant observation, document analysis and feminist life histories with her theory of representation identity. Representational identity theory is the connection of “who a legislator is with what she does” (p. 171). She argues, through close examination of key legislative decisions, that the combination of experience and identity can be used to usefully explain the behaviour of these legislators, and illuminate the diversity of experience and identity that exists within the group of Black women legislators. It is this key point which highlights the need for an intersectional approach that goes beyond the admittedly key categories of gender, race and class. In particular, Brown highlights how the differential experiences of the older and younger generations of Black women legislators leads them to different legislative decisions and approaches.

In an early chapter, the book describes the feminist life histories of the Black women legislators. This involves their reported life experiences, gathered during semi-structured interview. The purpose of this chapter is to establish the experiences of the legislators, in order to test the theory that these experiences influence their behaviour in the Maryland state legislature. However, there is also a secondary and important function of this chapter. It establishes convincingly that there is no uniform experience of being a Black woman, and lays out explicitly the differences that are so often hidden by studies which group Black women into a monolithic block. These differences stem from different class positions, marital status, sexuality, generation, education, location and motherhood status amongst other factors. The stories themselves are consistently fascinating, and while they do exhibit great variance, there does emerge a common sense of ambition among the interviewees; an ambition that combines with a sense of public service, and which led them to enter state politics. From a methodological perspective, the feminist life history approach is highly interesting. By using semi-structured interviews, Brown is able to observe not only what the interviews have to say about different issues, but also which issues they choose to raise throughout the interview. The methodology has clear connections with the major schools of feminist epistemology, as it prioritises and emphasises the experiences of these women, as told in their own words, and so allows for the complexity of experiences to be more accurately captured.

Three of the later chapters explore key legislative decisions, in order to test the representative identity theory. In one chapter, Brown explores the question of same sex marriage. This chapter establishes the problem of the “perceived wisdom” surrounding the Black community and the question of same sex marriage. While Brown points out that the data is not conclusive in showing that Black voters or politicians are more likely to oppose same sex marriage, she does also explore some of the potential causes for such opposition. When she combines the data from the feminist life histories with the voting records on a bill to legalise same sex marriages in Maryland, Brown finds a clear generational divide amongst Black women in the legislature. Such a generational division is not clear amongst other groups, and Brown argues that it highlights the impact of the different experiences of two generations. A similar generational divide is shown in her study of a domestic violence bill, but is not found in a study of legislation regarding the care of the elderly. Brown argues that this shows that it is only in some instances that Black women legislatures can be expected to respond to legislation in concert, and that these instances can be predicted based on an appreciation of the complex and diverse experiences and identities of these women law-makers.

As a case study of Black women in the Maryland legislature, Sisters in the Statehouse is fascinating. As one of the first attempts to utilise the intersectional approach in empirical social sciences, this book is pathbreaking. It will be read with great interest by those who study political representation as well as those who are grappling with intersectionality in their own fields. It is a book which embraces complexity and rejects simplifications and false binaries. As such it provides an excellent illustration of how identity, experience and power interact in a political context.

Muireann O’Dwyer is a Government of Ireland Scholar and PhD candidate, based in the School of Politics and International Relations in University College Dublin. She is in the PhD in European Law and Governance programme, which is involves engagement with the School of Law as well as with the school of Politics and International Relations. Her work focuses on building a feminist evaluation of new forms of EU governance, and aims to be intensively interdisciplinary. She holds degrees from NUI Galway (BA), UCL (MSc) and UCD (MEconSc). She tweets @mergito. Read more reviews by Muireann.

2 Comments