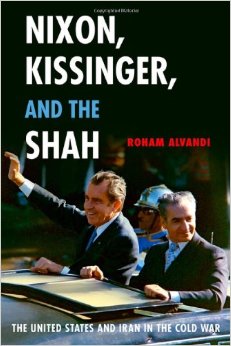

Nixon, Kissinger and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War gives new insight into the nature of the ties forged between Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, writes Vlad Onaciu. By drawing upon a vast array of documents from US, UK and Israeli archives and other historical sources such as memoirs and interviews, Roham Alvandi questions existing interpretations of US-Iranian relations during the Cold War.

Nixon, Kissinger and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War. Roham Alvandi. Oxford University Press. 2014.

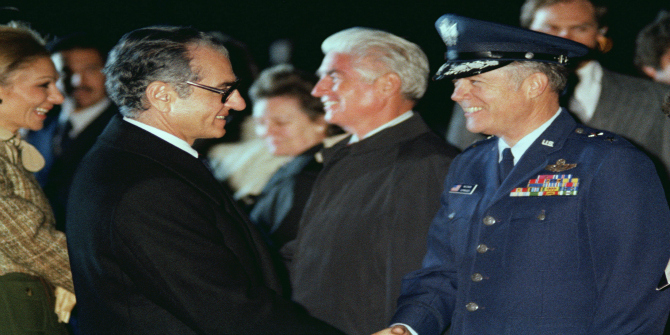

On 16 January 1979 Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled Iran and went into exile. The revolution continued for another month until, on 11 February, the monarchy was officially abolished. This marked the end of an era, one in which, for all its suffering and hardships, Iran had become one of the pillars of the Persian Gulf, being an integral part of US strategy and a regional power in itself.

On 16 January 1979 Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled Iran and went into exile. The revolution continued for another month until, on 11 February, the monarchy was officially abolished. This marked the end of an era, one in which, for all its suffering and hardships, Iran had become one of the pillars of the Persian Gulf, being an integral part of US strategy and a regional power in itself.

Roham Alvandi’s Nixon, Kissinger and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War brings both historians and other readers closer to understanding how the Shah juggled his foreign relations so as to advance his ambitions for the country he ruled. Written by a leading expert on the history of Iran, Alvandi’s book is the result of lengthy doctoral research spanning over several years. It can also be seen as a return to a lost way of writing political history, focusing not only on policies and decisions, but also on the people involved, and the relations between them. Alvandi thus distinguishes himself from other scholars such as Gholam Reza Afkhami and his biography, The Life and Times of the Shah (2008), a comprehensive approach to the Shah’s rule of Iran, or Trita Parsi’s Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran and the United States (2007), which insists on only certain aspects of US-Iran relations. Simultaneously, Alvandi’s book offers readers a new perspective on the Shah and Iran without ignoring the USA, in contrast to most historiography that mostly emphasises the latter (see, for example, Douglas Little, American Orientalism: The United States and the Middle East Since 1945 (2008), Michael J. Brenner, Nuclear Power and Non-Proliferation: The Remaking of US Policy (2009) or Patrick Tyler, A World of Trouble: The White House and the Middle East from the Cold War to the War on Terror (2008)).

Alvandi’s approach gives unprecedented insight into the evolution of the US-Iran alliance during the middle of the Cold War, daring to state that Shah Reza Pahlavi managed to create something akin to an equal partnership starting from his close ties with Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. Of course, such a theoretical path can leave out certain aspects of the analysis; yet this is assumed by the author from the beginning as his aim is not to write a comprehensive history of the subject, but rather to focus on three key episodes.

Firstly, he follows the evolution of the Nixon Doctrine, analysing changes between the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson administrations, and how each man’s relations with the Shah and perception of international politics influenced the way in which they treated Iran. Alvandi highlights the importance of British imperial withdrawal from the Middle East, which forced the United States to seek a different partner. This was a period in which the Shah made major concessions to the US, which, in the eyes of nationalists, served only to hinder Iranian sovereignty.

Secondly, the author analyses the relationship between Shah Reza Pahlavi, Nixon and Kissinger, the evolution from client to partner and the process of becoming the main pillar of American Gulf policy, with 1972 marking the zenith. He focuses not only on US aid in the forms of petroleum acquisition and arms selling, but also on how the Shah succeeded in drawing the Americans into the conflict in Kurdistan, with him acting as intermediary. Whether intentionally or as a consequence of his analysis, Alvandi tends to suggest that this ‘secret war’ in Northern Iraq put quite a strain on the Shah’s relations with the United States. One critique could be brought here: namely, that the author should have further expanded on the issue of rising oil prices in the broader context, thus offering a more comprehensive explanation for the Shah’s affordance of such high military spending, and his distancing of the United States.

The last part of the book tackles the erosion of US-Iranian relations in the context of the Watergate Scandal, the ascent of the Carter Doctrine, Nuclear Non-Proliferation and the Shah’s ambition to acquire new means of producing energy and nuclear weapons. The author stresses that, apart from the negative impact of the ‘White Revolution’ and increased military spending, Shah Reza Pahlavi also had to deal with people less friendly to his cause in Washington D.C. In this section, Alvandi presents the Iranian ruler as engaged in a desperate struggle to maintain his primacy in the Gulf, whilst also dealing with increasing contestation at home.

One key aspect that the author stresses throughout the book is that of the Shah’s image in his country, and how this played a role in his demise. Alvandi argues that ever since the coup which ousted Mohammad Mossadeq, the ruler had been confronted with the need to gain legitimacy with nationalists, proving he was not a mere pawn of US imperialism. In fact, Alvandi links this to the Iranian ruler’s insistence on having a strong army as this would be his best means of holding on to power. What he illustrates throughout the entire book is that the Shah always sought US commitment to the security of his regime, something he often felt was absent.

Alvandi uses an impressive array of sources, in so doing distancing himself from other authors who have approached the topic. He shuffles between documents of various state and presidential administration archives and libraries (of Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and Ford) from both the United States and the United Kingdom (namely, the British Foreign Office), whilst simultaneously using online volumes of documents, such as those of the Israeli State Archives. Admitting the difficulty of gaining access to Iranian State Archives, the author managed to gather alternative historical sources, such as memoirs and interviews. While the aspects covered by the book might not be comprehensive, Alvandi’s approach towards the information he used is.

In the end, we inevitably question the traditional historical interpretation of the nature of the partnership between Iran and the United States. It will be nearly impossible for any reader to assert who had used who in this relation, as both sides gained what they aimed at securing. The Shah succeeded in considerably increasing his regional prestige, whilst the United States contained the spread of communism and maintained supremacy in the Gulf without any direct military commitment.

Vlad Onaciu is currently a second-year PhD student in the Faculty of History and Philosophy at ‘Babes-Bolyai’ University where he previously finished his BA and MA in contemporary history. His doctoral research focuses on issues regarding the lives of workers in factories during the communist regime in Romania. His academic interests include the history of communism, oral history, international relations (mainly civilisational studies) and 19th and 20th Century history in general.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.