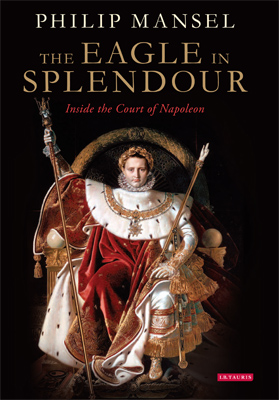

In this re-release of The Eagle in Splendour: Inside the Court of Napoleon, Philip Mansel details the structure and quotidian functioning of Napoleon’s court. Marion Koob praises this fascinating read for its illuminating and riveting anecdotes as well as Mansel’s persuasive account of the close relationship between the day-to-day running of court life and Napoleon’s broader political convictions.

The Eagle in Splendour: Inside the Court of Napoleon. Philip Mansel. I. B. Tauris. 2015.

According to Philip Mansel, Napoleon was awful company. He was described by his contemporaries as rude, prone to fits of rage and happy to humiliate nobles, officers of state and foreign ambassadors alike. He loved to tell his courtiers that they were being cheated on by their spouses and, when in a good mood, he would show his endearment by tweaking a noble’s ear or cheeks – sometimes so hard that they cried and wore bruises for days.

According to Philip Mansel, Napoleon was awful company. He was described by his contemporaries as rude, prone to fits of rage and happy to humiliate nobles, officers of state and foreign ambassadors alike. He loved to tell his courtiers that they were being cheated on by their spouses and, when in a good mood, he would show his endearment by tweaking a noble’s ear or cheeks – sometimes so hard that they cried and wore bruises for days.

As a court historian, founding member of The Society for Court Studies and expert on court life across French and Turkish history, Mansel reveals a different facet of the French Emperor in his re-released The Eagle in Splendour: Inside the Court of Napoleon. In this work, he argues that Napoleon carefully constructed his court as a means of wielding power across his ever-expanding territories and of casting influence on the rest of Europe. From the court’s structure can be gleaned a sense of Napoleon’s political ideals. Mansel details the day-to-day of court life in vivid detail, making it easy to imagine how a noble – new or old – would have perceived France’s new rulers.

The author argues that Napoleon was an absolutist monarch, rather than an enlightened revolutionary as he is often construed. His court was organised in continuation of the French Bourbon Kings; his symbols of power displayed with greater emphasis than that of his predecessors; and his rituals more formalised. The Emperor sought to establish a Bonaparte ruling line and, as such, was intent on cementing his power. In light of the publication of Andrew Roberts’s biography Napoleon the Great (2014) last year, Mansel’s re-release makes for an interesting point of comparison.

The author clearly shows that Napoleon’s court was a meld of the new and the unexpectedly traditional, a point on which he expands in Chapter Four, ‘The Courtiers’. His was the first in history in which senior positions were held by non-nobles. Prior to Napoleon’s rule, these were only available to the three existing categories of nobility: la noblesse présentée (nobles attending court), la petite noblesse (landed gentry) and la noblesse de robe (those holding judicial or administrative posts). Service to Napoleon was attractive to all; for nobles and non-nobles, supporters or opponents of the revolution, the Emperor rewarded well.

Appointments were used as a means to win over opponents of the regime. Individuals were selected from parts of the former opposition, from old aristocratic families or for being enemies. Napoleon marked his power by only recognising titles which he himself had awarded, leading to endless jokes in which courtiers purposefully confused their old and new names.

Image Credit: FR Society 16: The Coronation of Napoleon (Francisco Osorlo)

Image Credit: FR Society 16: The Coronation of Napoleon (Francisco Osorlo)

The inclusion of those from more modest backgrounds did not, however, mean that the court was less elitist. Mansel notes that while trying to establish its legitimacy, Napoleon created a court more rigid, more arrogant and less socially secure than most other European monarchies. Mansel compares the Bourbon Kings and other, older European dynasties favourably to Napoleon, commenting that that they were less removed from their people, were more relaxed and their courts had a friendlier atmosphere.

Courtiers very much used their service to the Emperor as a means to an end, as Mansel argues in Chapter Five, ‘Ends and Means’. The author contends that with almost no exception, their motivations lay in advancing themselves and their families rather than loyalty to their rulers. Being granted a position at court was a near-guarantee of wealth and success. The Emperor was generous to those who served him as he was convinced that it was in his interest. For instance, he distributed lands from his conquests as rewards, giving his courtiers a personal stake in his military success. He also approved of nobles using their roles to advance their families as well as themselves. This, he believed, was another way of guaranteeing united loyalty. Thanks to this, nobles holding positions at court were especially effective in helping or hindering acquaintances’ careers: Mansel describes the court as a great employment bureau. The author notes that gaining a position at court was also a good way of playing catch-up for those who had not previously held positions in government due to their opposition to previous regimes.

While many testimonies describe the court as sumptuous, it was also considered to have an unpleasant atmosphere: men said that they were bored by the entertainments, while ‘women were always afraid that the emperor would criticise the number of their lovers or the quality of their clothes’. Mansel portrays the court as having ‘a void at its heart’. In other words, it lacked love and respect for the royal family usually present in other regimes. Napoleon’s behaviour did not help the case: he was reputed for being rude and aggressive in an age in which good manners were studied carefully. Until 1810, Mansel explains, Napoleon’s lack of tact was mitigated by the charm of his first wife, Josephine. However, his second wife, Marie-Louise, was too reserved to carry out the same role. It is telling that many of the courtiers chose to live outside of the palace of Les Tuileries, whereas under the Bourbon monarchy, all had been fighting for lodgings in Versailles.

The Eagle in Splendour is a fascinating read. Mansel is excellent at selecting and retelling illustrative anecdotes. His account of the organisation of court life is riveting, and he argues persuasively that Napoleon’s political convictions were spelled out in the organisation of his day-to-day life and entourage. More than this, they also reflected his character flaws. Mansel is convinced that these were what led to his demise – his personality left little room for unconditional loyalty.

As cited above, Napoleon’s court was in many ways unpleasant. Yet Mansel also vaunts its more flattering aspects. It was remarkably international: it hosted aristocrats from around Europe; it included non-nobles; and although monarchical court law was regressive, the laws Napoleon imposed in nations ruled by his siblings were progressive.

Mansel uses a wide range of sources, from papers in the Archives Nationales in Paris and the Bibliothèque Nationale to various private archives, as well as many memoirs published during the period.The book needs little improvement, but it could have benefitted from an introduction that more clearly signposts the structure of subsequent chapters; at present, it is somewhat confusing. More importantly, Mansel seems to favour the ‘old families’ and monarchies of Europe in a way that is not sufficiently justified and his criticism of the Napoleonic Code, the Emperor’s major contribution to the Western legal system, is unclear. It would have been useful to have expanded on both of these points. This book is nonetheless highly recommended to anyone interested in Napoleon and his legacy, court history and, more broadly, the creation and shaping of political institutions.

Marion Koob has a BSc in Government and Economics at the LSE and an MPhil in International Relations at the University of Cambridge. She has worked in Polis, the LSE’s journalism think-tank, and is now at the British Film Institute. Read more reviews by Marion Koob.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.