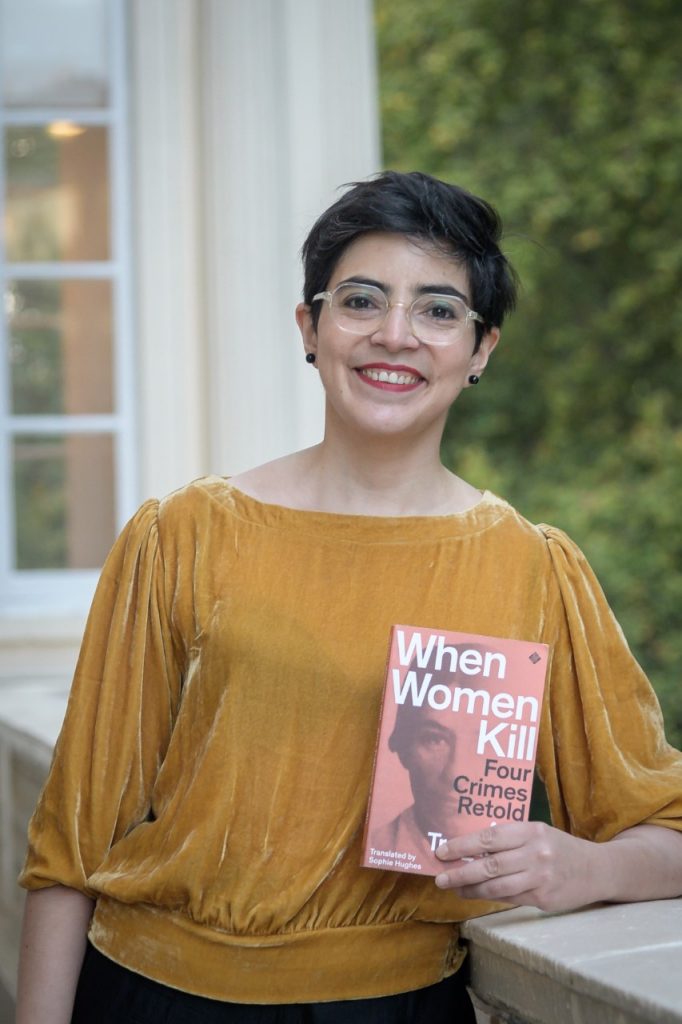

We speak to Alia Trabucco Zerán about When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold, winner of the 2022 British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. In the book Alia explores four murders committed by Chilean women in the twentieth century. She critically examines how the crimes not only transgressed criminal laws, but gender norms too, thereby becoming windows through which to examine the changing meaning of femininity.

Alia will be in conversation about When Women Kill with Fatima Manji, Channel 4 News broadcaster, journalist and Book Prize jury member, at 6pm on Monday 16 January 2023. Register for free for this online British Academy event organised in partnership with the London Review Bookshop.

The 2023 British Academy Book Prize is now open for submissions until 28 February 2023. Further information can be found on the British Academy website.

Q&A with Alia Trabucco Zerán on When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold (translated by Sophie Hughes). And Other Stories. 2022.

Q: You begin When Women Kill by describing how people often mishear your book as being about women who have been murdered. What does this misunderstanding suggest about the social positioning of women – and specifically women killers?

Q: You begin When Women Kill by describing how people often mishear your book as being about women who have been murdered. What does this misunderstanding suggest about the social positioning of women – and specifically women killers?

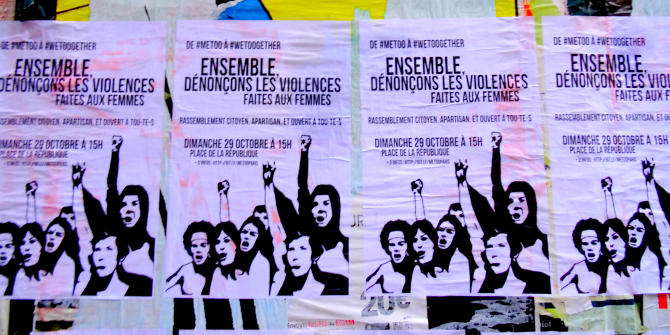

It is simple and telling: it’s easier to imagine a woman who has been murdered than a murderer woman. Which basically tells us the following: we have normalised violence towards women to the point that those images, the ones that victimise women, are immediately and ‘naturally’ available to us. We don’t raise an eyebrow if we see an armed man, but an armed woman? A murderer? That is unimaginable.

It is important to clarify that I am not suggesting that there should be more female killers. I am just shedding light on a taboo topic, which allows us to examine what we consider normal and abnormal (and why), and how we react to that. How do different societies punish women who transgress gender norms? If you look at my book’s cases closely, critically, they are windows from where to examine the changing meaning of femininity and this is an important quest for feminism, although an uncomfortable one.

Q: How can exploring the lives and crimes of women killers contribute to feminist inquiry?

I think this is one of the key questions of my book. If you write a book on women who have been killed, on femicides, for instance, it is obvious: you are denouncing sexist violence, you are making visible a reality that is often hidden, you give women a voice. So why talk about an exceptional issue, such as women who kill? Well, this is it: women who kill are indeed rare, comprising only 5 per cent of the murders committed in the world. However, something extraordinary happens when they do kill. Society is fascinated by this and reacts. The press and the legal system go crazy and representations proliferate: films, novels, plays, songs. Why?

The answer is the answer to your question: because when women kill, they not only transgress criminal laws. They also transgress gender norms, the norms that tell us all, all women, how we should behave. And thus society tries desperately to put these women back into their roles, calling them crazy, hysterical, witches, vilifying them or making them unreal by associating them with mythical figures such as Medea. When you critically examine this reaction to extreme cases, then you can see how society, in less extreme situations, punishes women for not complying with other gender norms: when women decide not to be mothers, when women decide to work in ‘masculine’ jobs, when women transgress the roles we have been assigned. So, it is transgression that interested me, really. Or as philosopher Sara Ahmed says: ‘the history of feminism is a history of transgression.’ And I am trying to contribute to that.

Q: How did your training as a lawyer shape the project? Did writing the book cause you to reflect on your past training differently?

I will be honest here. When I decided I wanted to write novels and essays, I was very self-conscious about not having proper literary training. I started an MFA in Creative Writing in Spanish at NYU just after I graduated as a lawyer and I felt like an impostor. Then I published my first novel, The Remainder, also translated by Sophie Hughes, and I started a PhD. This is when I decided to revisit that past through my research on women who kill. And it was so important for me. I suddenly realised I could not only look at legal documents from the new perspective given to me by literature, but could also ask literary materials questions such as: does this book punish women? Is this a normative book when thinking about gender? So I approached literature with the eyes of a lawyer too. When Women Kill helped me better integrate my biography and the things I am interested in. I love literature, but I am also very interested in the interactions between literature and other fields, such as law. The interdisciplinary element is not only theoretical for me, it is biographical.

Q: When Women Kill intertwines true crime narrative and your own research diaries. Did you always plan to weave together these different elements?

No, I didn’t. But before answering that, I find it fascinating that this book qualifies as ‘true crime’ in English. We don’t use that category in Latin American literature, or at least not that much. So, my book is described as a hybrid essay, with diary entries and ‘crime chronicle’ or ‘crónica roja’, never as true crime. But that is a detour. I wanted to use the structure ‘crime chronicle’, the sensationalist element, and question it. But during the research, I realised I really didn’t want to write in that plural voice so common in academic writing, where you blur the fact that it’s an individual, with a particular view, a particular standpoint, behind the work. A woman, in my case, writing in a certain context, from a situated body, dealing with the reactions anyone faces when approaching a taboo topic. So the diaries allowed me to introduce myself, to say: well, I am here, dear reader, going from one place to the next, finding it hard to deal with this material, not finding the archives, being frustrated, irritated, uncomfortable, scared, happy, fascinated, etc. This is a political statement in the end: a book is not only the result, but a process. And early on I realised it could be valuable to use this material and make a political statement too.

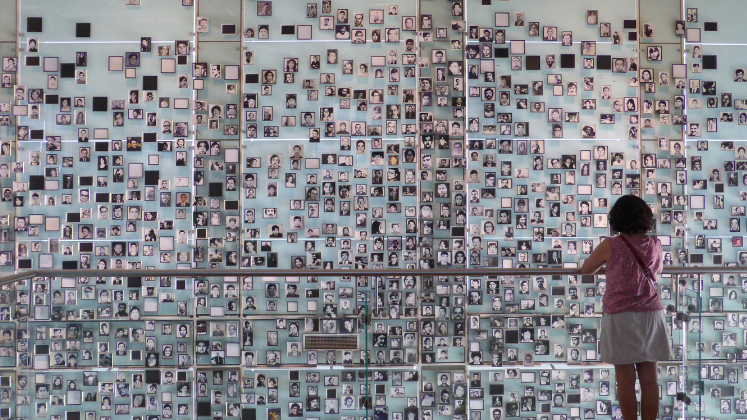

Q: What was your experience of immersing yourself in the histories of these violent crimes? How does a researcher take care of themselves when doing so?

What an interesting question. It was tough at times. It was tough looking at very explicitly violent images; it was tough dealing with people who found me suspect when entering judicial archives that, in the case of Chile, contain material from the dictatorship that is still a secret. And it was very, very tough ethically when I found myself empathising with the murderer. I got back home and asked myself: what is it about them that I find not only fascinating but that I can relate to? It wasn’t their violent acts of murder, but their transgression of gender norms that drew me to them. The fact that they were not only judged for killing, but for not complying to the norms that regulate femininity. So, to be honest, the way I took care of myself and my research was never avoiding the difficult questions and feelings that sometimes didn’t let me sleep. Facing them, trying to understand them and also discussing them with people I trusted and respected intellectually, such as Claire Lindsay, my tutor at UCL who was incredibly supportive and brilliant at all times.

Q: When Women Kill won the 2022 British Academy Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. What did it mean to win this award? What is the importance of facilitating global understanding through non-fiction today?

It was an unforgettable night and a very surprising one, I have to say. I didn’t expect to win, not only because the other books were truly remarkable, but also because my book looks at a very polemical, sometimes taboo topic, so I thought it could be an uncomfortable read. And indeed, the members of the jury confirmed that it was, but this is why they liked it and this is why it makes me so proud. I don’t think literature should make you feel comfortable. I am suspicious of those books that you close and then feel calmed, anesthetised. Like a placebo to tolerate the society we live in. I prefer literature that makes you think, that makes you question yourself, your position in life, even your relationships. Critical works, fiction, non-fiction: for me, it makes no difference. I love literature that moves you intellectually and emotionally, and I hope I can write books that contribute to that. On that same line, I think cultural understanding doesn’t necessarily come from consensus, from uniformity, from sameness. It can come from tough discussions, from difficult topics. Hopefully my book can contribute to thinking about masculinity and femininity in new terms. For societies to stop normalising violent men, and stop considering women as passive and powerless.

Q: Your book was translated into English by Sophie Hughes. How is the work of translators integral to the pursuit of global cultural understanding?

I am a keen reader of translated literature and an admirer of what translators are able to do with their work. I also love reading about the translating process, as I don’t find it that different from the writing process and the issues writers face: which word to choose? Is the rhythm of this sentence ok? What exactly do I/they mean by this? Without their work, which is intellectually and artistically very challenging and very important, there would be no cultural understanding at all. That said, I don’t approach translated literature to find out about a culture or a country I don’t know much about. This is what history is for. I read translated literature because it’s good literature, many times exceptional. And I also love what a translated work does to the language it is translated into: sometimes it implies putting together two words that wouldn’t normally be together, and this has an impact in language, twisting it, making it richer and making us culturally richer too.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.