In A Theory of the Drone, French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou seeks to comprehend how drones have revolutionised contemporary warfare and to deconstruct the various narratives at the heart of what has become a conceptual and legal dilemma. Chamayou masterfully dissects and helps elucidate much of the twisted logic behind the justification of drones as well as their revolutionary impact on modern conflict, writes Audrey Borowski.

A Theory of the Drone. Grégoire Chamayou (trans. by Janet Lloyd). The New Press. 2015.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

In the past decade, the deployment of hunter-killer drones has grown exponentially so that they have come to symbolise the ‘War on Terror’. Curiously, despite their proliferation, they have received relatively little academic attention. In A Theory of the Drone, French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou seeks to comprehend how drones have revolutionised warfare and to deconstruct the various narratives at the heart of what has become a conceptual and legal landmine.

In the past decade, the deployment of hunter-killer drones has grown exponentially so that they have come to symbolise the ‘War on Terror’. Curiously, despite their proliferation, they have received relatively little academic attention. In A Theory of the Drone, French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou seeks to comprehend how drones have revolutionised warfare and to deconstruct the various narratives at the heart of what has become a conceptual and legal landmine.

The drone’s philosophy can be summed up in the following motto: ‘projecting power without projecting vulnerability’. Ready to strike at any moment, its ‘unblinking stare’ reigns omniscient and omnipotent over the lives of those it surveys. With it, the body of the fighter and their weapon are radically separated. As one kills, one can no longer be killed. The enemy can henceforth be eradicated from behind the safety of a computer screen, thousands of miles away from the theatre of conflict. This radical imbalance in exposure to death challenges the very premise of warfare.

The global ‘War on Terror’ has ushered in a new kind of warfare. It is no longer circumscribed in time or location, but has been extended indefinitely, operating transnationally and impervious to boundaries and the principle of territorial integrity which has traditionally attached to it. By reducing the zone of conflict to the body of the enemy or prey to a given ‘kill box’, the technological precision of drones has paradoxically turned the whole world into a battlefield. Warfare has slipped into an essentially preventive manhunt aimed at rooting out emerging threats and denying terrorists ‘sanctuaries’, including in zones of peace.

The dronisation of warfare comes as the natural culmination of shifts initiated in the mid-1990s and governed by the politically motivated imperative of minimising risks to one’s own combatants. The prospect of a ‘war without risks’ was first raised during the Kosovo War in 1999, when pilots were forbidden to fly below an altitude of 15,000 feet: this meant that they were nearly out of reach of the enemy anti-aircraft defences, but it also corresponded to a loss of accuracy for airstrikes. The preservation of combatant lives increasingly took precedence over the obligation to minimise the risk for enemy civilians, thereby effectively reinstating a radical inequality in the value of lives between those that are ‘expendable’ and those that are ‘absolutely sacrosanct’.

The deployment of drones thus undermines the very premise on which modern warfare rests whereby ‘one cannot kill unless one is prepared to die’. Killing and exposure to death are concomitant in the classical model of warfare. In the Early Modern period, the Dutch thinker Grotius, meditating on the permissibility of recourse to poison, had for this reason ruled it unlawful to deprive one’s enemy of the ‘power of defending oneself’. Samuel von Pufendorf later reasserted the combatant’s legal equality. Without this rapport of reciprocity, war degenerates into acts of simple execution, as in the case of the drone. By suspending this rapport of reciprocity, drones erode the legal framework which made killing in armed conflicts permissible in the first place.

With drones, the right to kill is no longer grounded in the legal equality of the belligerents, but has been rearticulated around the notion of ‘just cause’. Warfare has morphed into police action governed by claims of moral superiority. Drone strikes radically defy established categories of warfare and the legal paradigms which hitherto underpinned them, plunging the very notion of ‘war’ into crisis. They hover somewhere between the law of armed conflicts – which requires sustained, persistent fighting occurring in a theatre of conflict – and law enforcement – whereby the use of lethal force is used as a last resort.

Drones have so far evaded scrutiny on account of their particular ethical nature. Because they save national lives, they have been hailed in some quarters as the ‘humanitarian’ weapon par excellence: ‘There’s a war going on and drones are the most refined, accurate and humane way to fight it,’ Jeff Hawkings of the US State Department tells us. The exercise of lethal violence has now even reclaimed humanitarianism for itself. Chamayou’s account reveals itself particularly apt at teasing out the various sophisms which underscore much of the argumentation behind the deployment of drones. A widely peddled claim that he debunks is derived from the drone’s increased technical precision. This has been used to suggest the capacity to distinguish more effectively between civilians and terrorists. Ultimately, however, as Chamayou reminds us:

The precision of the strike has no bearing on the pertinence of the targeting in the first place. That would be tantamount to saying that the guillotine, because of the precision of its blade – which, it is true, separates the head from the trunk with remarkable precision – makes it thereby better able to distinguish between the guilty and the innocent (143).

Indeed, by doing away with combat altogether, drones have abolished the very possibility of discriminating between combatant and non-combatant. Ultimately, in the absence of combat, how does one establish combatant status? How does one designate the enemy? Guilt is no longer manifest through observation: it is suspected on the basis of a ‘pattern of life’ analysis and effectively confirmed après coup, since everyone killed in a ‘signature strike’ is counted as a legitimate target. It is the result of a ‘blind’ process; strikes often carried out ‘without knowing the precise identity of the individuals targeted’, but whose behaviour conforms to ‘a signature of pre-identified behaviour that the US links to militant activity’. With drones, it is the act of killing itself which has been automatised.

The dronisation of warfare has sounded the death knell of a certain military ethos based on heroic self-sacrifice and one’s readiness to die. Military strategist Carl von Clausewitz captured its essence in his magnum opus On War:

We should not forget that our mission is to kill and be killed. We should never close our eyes to that fact. Making war by killing without being killed is a chimera; making war by being killed without killing is inept. So one must know how to kill, while being ready to die oneself. A man who is committed to death is terrible.

The ethic of heroic sacrifice now strikes us as abhorrent and has been superseded by that of vital self-preservation. In a bid to rehabilitate and re-humanise an essentially cowardly act, military virtue and heroism have been reformulated in psychic terms. Physical wounds have been converted into psychic ones. Ethicists and philosophers have been recruited in this effort to legitimise otherwise faceless and anonymous acts of violence, spawning a new discipline: ‘necro-ethics’. Through this semantic assault, war becomes peace and killing ‘humanitarian’ and moral.

Crucially, though, the deployment of blind violence terrorises entire populations and further risks antagonising them rather than ‘winning their hearts and minds’, as David Kilcullen, former advisor to General Petraeus, has been keen to point out. Counter-insurgency has given place to counter-terrorism and long-term political strategy has been sacrificed in favour of immediate tactical success. Technology has simply rendered political analysis superfluous. The enemy are no longer political adversaries to be opposed, but criminals or ‘aberrant individuals’, seen as quite simply mad or incarnations of pure evil to be eliminated one-by-one. In this sense, drones implement a binary reading of the world between good and evil, one which threatens to plunge the world into a ‘war without victory’. Chamayou continues: ‘The scenario that looms before us is one of infinite violence, with no possible exit; the paradox of an untouchable power waging interminable wars toward perpetual war’ (71-72). Not only that, but by placing armed forces out of reach, drones effectively divert reprisals toward their own population.

Finally, the dronisation of armed forces alters the conditions of decision-making in warfare. By transferring the various financial, demographic and political costs of war from the population to a machine, it drastically lowers the threshold of recourse to violence and becomes the default option for foreign policy. Paradoxically, the allegedly ethical nature of drones renders recourse to them more frequent, giving rise to military action which would otherwise never have taken place. Peter W. Singer has called unmanned systems ‘a technology that removes the last political barriers to war’. Democratic pacifism morphs into democratic militarism with its immunised bodies and psyches.

While most of Chamayou’s remarks are valid and commendable, one cannot help wondering whether his account smacks of naivety. He faults historian David A. Bell for attempting to justify drone strikes through the ‘reassuring discourse of historical permanence’ when he, on the other hand, tends to reduce history to the colonial past. Throughout history warfare has always been a process of seeking to gain the advantage, harnessing technology to this aim. As Bell reminds us, ‘using technology to strike safely at an opponent is as old as war itself’, each attempt eliciting its own spate of criticisms and condemnations. We no longer live in a world of duels or conventional warfare. First came insurgency, now terrorism. Warfare has changed and threats take on new shapes, calling for the most adapted responses in a context of increased uncertainty and unpredictability. Should drones not simply be read as the latest incarnation of a perennial dynamic?

Drones are undeniably imperfect weapons: they fan the flames of hatred against the West by denying political grievances, set dangerous precedents for other powers seeking to carry out extra-judicial executions across the globe and overall lack transparency and accountability. Yet, they have also demonstrated their effectivity in fostering a sense of helplessness and shrivelling terrorist leadership otherwise left to thrive in the face of governmental inaction – arguments that Chamayou glosses over. Nonetheless, Chamayou masterfully dissects and helps elucidate much of the twisted logic behind the justification of drones as well as their revolutionary impact on warfare.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

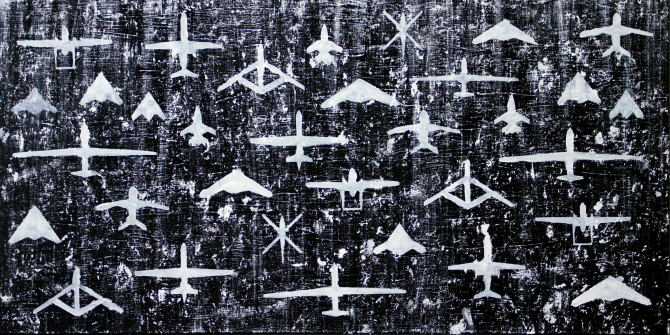

Image Credit: Dawn Drone Pilot (Bit Boy, CC BY 2.0).

5 Comments