With the publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961 and her famous battle against New York City city planner, Robert Moses, Jane Jacobs established herself as one of the key figures of US urbanism. While accounts of Jacobs’s life tend to depict her as a housewife who spontaneously became an activist, Becoming Jane Jacobs seeks to explore her early life and intellectual development. Peter L. Laurence shows how Jacobs’s influential approach was shaped by her experiences as a writer and critic within an intellectual community of architects and urbanists. While Jacobs remains a somewhat enigmatic figure, Jenny McArthur applauds Laurence’s lucid, fascinating narrative that will be of value to anyone interested in cities, urban politics and planning.

Becoming Jane Jacobs. Peter L. Laurence. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2016.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) began as a harsh critique of the urban planning paradigm adopted in US cities in the 1950s, and went on to become a canonical text. The author, Jane Jacobs, has long been remembered as a central figure in changing the way we think about cities; however, apart from her writings themselves, there is little to understand how she developed her ideas. In Becoming Jane Jacobs, Peter L. Laurence examines Jacobs’s intellectual life in the years prior to the publication of Death and Life.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) began as a harsh critique of the urban planning paradigm adopted in US cities in the 1950s, and went on to become a canonical text. The author, Jane Jacobs, has long been remembered as a central figure in changing the way we think about cities; however, apart from her writings themselves, there is little to understand how she developed her ideas. In Becoming Jane Jacobs, Peter L. Laurence examines Jacobs’s intellectual life in the years prior to the publication of Death and Life.

Laurence rejects the common stereotype that Jacobs was a housewife who had paid particular attention to the street life outside her Greenwich Village home before extrapolating these ideas across cities in general. A closer examination of Jacobs’s early life and work shows that a greater breadth of experiences and foundational writing roles contributed to Death and Life in unexpected ways. Attention is therefore given exclusively to Jacobs’s early years; her later works and much-publicised activism against the infrastructure projects of New York planner, Robert Moses, are not covered in this text.

Becoming Jane Jacobs is timely. There is still strong debate over how cities should be planned and designed, and while many of the twentieth century’s urban planning paradigms have become outdated, Death and Life remains an authoritative source. However, there is a tendency for Jacobs’s writings to be misappropriated by different, often contradictory, partisan perspectives to reinforce their own claims. Jacobs’s worldview didn’t fit neatly into the usual dichotomies – was she pro- or anti-development? For or against the free market? For or against regulation? Drawing exclusively from her writing, evidence can be found for both sides of these arguments, making it easy to cherry-pick extracts to support either stance. Therefore, to move past superficial interpretations of Jacobs’s work and to understand her thinking in more depth, Laurence’s text fills an important gap.

This book situates Death and Life within the personal life of its author and the wider context in which Jacobs’s ideas developed. Contrasting her experience of New York with the coal town she grew up in, Laurence suggests that rural economies were as instructive as urban ones in Jacobs’s understanding of economic specialisation and production. Jacobs grew up in the industrial town of Scranton, Pennsylvania, and did not experience urban life until shifting to New York in 1934. She arrived after the worst of the Depression, when New York had a sense of ‘cautious optimism’, boosted by the promise of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal projects. Finding work was not easy at this time, although, for the indomitably curious Jacobs, navigating the city in response to job advertisements served as a kind of fieldwork for her writing on urban economies.

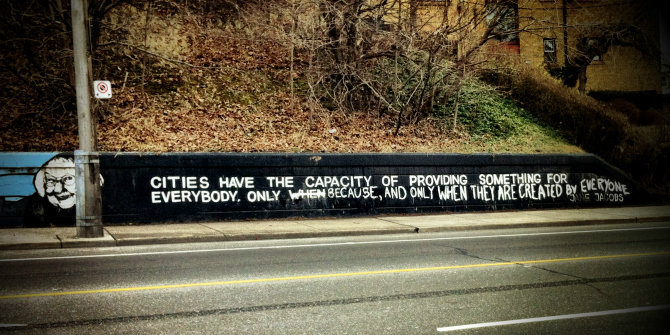

Image Credit: ‘lesson for Rob Ford’ by Ryan licensed under CC BY 2.0

Becoming Jane Jacobs shows that Jacobs’s credentials were well-established by the time she came to write Death and Life. Her writing career began inauspiciously with a metals industry trade publication, before moving on to propaganda writing for the US Office of War Information during World War II and eventually becoming a critic for Architectural Forum. Over this time Jacobs proved her formidable writing talent and ability to take to new assignments without hesitation. Additionally, the scope of her interest extended well beyond New York City: she had written on urban development in Cleveland, Philadelphia and Washington DC, and her wartime propaganda writing surveyed life across the United States.

Reviewing these formative years and the influence of her education also shows how earlier studies outside the fields of planning or architecture shaped the critique brought into Jacobs’s urban scholarship. Later on in her career, Jacobs was frequently labelled as too ‘uneducated’ to be an authority in the field of urban development and architecture. Being Jane Jacobs tracks her undergraduate degree at Columbia University, including wide-ranging courses on geology, zoology, law, political science and economics. While university study and her various writing posts built a sound understanding of the social and physical sciences, it is perhaps the absence of training in a technical discipline such as architecture or engineering that allowed her to form a critique from outside the established norms of urban planning. This critique also reveals why Jacobs has remained a canonical author. She was both an avid modernist and focused persistently on the ‘study of the ‘‘use’’ of things’, but also offered a necessary critique of modernity and how it shapes our cities:

She saw that a city required flourishing public and quasi-public institutions. Public life was an important element of civilization and liberty, according to Jacobs, and it required a spatial infrastructure to thrive.

Modernist architecture followed the ethos of ‘form follows function’. While Jacobs adopted this notion, her view was that cities served primarily human functions. While the standard practice of city planners catered for vehicle traffic and land development at the expensive of a thriving public realm, Jacobs fought hard to restore urban spaces to the city’s inhabitants. Death and Life discusses at length the sociological aspects of street life: continuous use of the space and ‘eyes on the street’ by local residents or workers for the safety of those using it. Laurence shows that these findings were not solely the outcome of Jacobs’s experience on her own block, although New York City no doubt provided a huge amount of field research. The standard planning paradigm diverged sharply from her views:

She was unforgiving of arrested mental development in the younger generation of planners and designers. Anticipating a theme found in her subsequent books, she wrote, ‘It is disturbing to think that men who are young today, men who are being trained now for their careers, should accept on the grounds that they must be ”modern” in their thinking, conceptions about cities and traffic which are not only unworkable, but also to which nothing new of any significance has been added since their fathers were children’.

Laurence writes lucidly, and the breadth of research supporting this book is impressive. While as a reader I found Jacobs’s character to be almost as enigmatic at the end of the book as when I began, the sources of her ideas were explained more clearly. Jacobs’s extraordinary sense of curiosity is also brought forward strongly in the text. Whether tasked with writing technical articles on ferrous metals or producing wartime propaganda (we are told it was ‘more public relations, than misinformation’), Jacobs was prolific. Even when the subject matter was dry, as with her writing for Iron Age, an interesting narrative could be found for any topic. Becoming Jane Jacobs is sensitive to avoid making a caricature out of its subject, and also tracks how Jacobs’s early idealism was stifled by experiences in New York and the apparent intent of urban planners to ‘think up schemes that make [the city] uninhabitable’. The book is particularly relevant for urban scholars to ground academic interpretations of Jane Jacobs’s writing, but the narrative and depth of this research have produced an equally valuable read for those interested in cities, urban politics and planning.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

8 Comments