What is human happiness and how can we promote it? In Happiness Explained: What Human Flourishing Is and How We Can Promote It, Paul Anand argues that we should move beyond GDP to instead consider subjective wellbeing as a substantial, significant and necessary measure of national, governmental and individual success. While Jake Eliot suggests that the book does not always fully contend with the significant challenge of deploying this framework in the realm of public policy, it does sterling work of mapping the emergent territory of happiness and wellbeing and convinces of the need to move beyond narrow understandings of outcomes.

Happiness Explained: What Human Flourishing Is and How We Can Promote It. Paul Anand. Oxford University Press. 2016.

Happiness policy has been on a seemingly irresistible march towards the mainstream. What began as think-tankers and academics swapping anecdotes about wellbeing in Nordic countries and Bhutan’s measure of ‘Gross National Happiness’ has matured to the point where the United Nations has published four World Happiness Reports, ranking nations by their reported happiness levels. While, in the UK, in 2010 the former coalition Government proposed a new national measure on wellbeing to ‘help government work out, with evidence, the best ways of trying to help to improve people’s wellbeing.’

Happiness policy has been on a seemingly irresistible march towards the mainstream. What began as think-tankers and academics swapping anecdotes about wellbeing in Nordic countries and Bhutan’s measure of ‘Gross National Happiness’ has matured to the point where the United Nations has published four World Happiness Reports, ranking nations by their reported happiness levels. While, in the UK, in 2010 the former coalition Government proposed a new national measure on wellbeing to ‘help government work out, with evidence, the best ways of trying to help to improve people’s wellbeing.’

Paul Anand’s latest book Happiness Explained: What Human Flourishing Is and How We Can Promoted It moves swiftly over this well-covered ground, setting out for the generalist reader the limitations of relying on measures of gross national income as indicators of the relative success of a country and its people. From this starting point, Anand builds his case that subjective wellbeing is a substantial, significant and necessary organising focus for government policy.

The book’s theoretical framework is underpinned by the capability approach established by Amartya Sen and further developed by Martha Nussbaum. Rather than define human happiness by an amalgamation of the kind of outcomes measurable through wellbeing surveys, the capabilities approach emphasises more subjective and experiential aspects of wellbeing. Anand sets out how the capability approach can inform a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of happiness. In this book’s framework, wellbeing is contingent on resources – financial, natural, human and social – and the individual’s skills, abilities and opportunities to convert these resources into valuable outcomes.

This focus on subjective wellbeing opens up space for Anand’s distinctive contribution in Happiness Explained, drawing on insights from social psychology to demonstrate how the capabilities approach developed by Sen and Nussbaum can create a framework for wellbeing for individual citizens and policymakers. As Anand observes, economists are well accustomed to regarding freedom and choice as important; but to explain happiness, freedom and choice need to be connected to a perceived sense of control in our day-to-day lives and the experience of making this manifest through the structured activities we engage in.

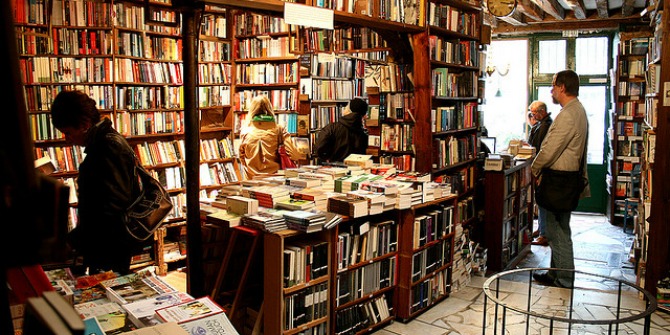

Image Credit: (Rachel Kramer CC2.0)

Image Credit: (Rachel Kramer CC2.0)

For anyone unfamiliar with the evidence base on subjective wellbeing, Anand conducts a masterful and rapid tour of studies from economics and psychology, exploring how capabilities for wellbeing are experienced and deployed in different contexts and across the life course. As one would hope from a volume focused on generalist readers, there are some flourishes and surprises worthy of Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker articles or Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt’s Freakonomics. Demonstrating the variety of different factors that drive life satisfaction, for instance, Happiness Explained highlights a 2012 comparison study of US and UK adults’ reported reasons for wellbeing in terms of what people are able to do at home, in work and in the community. This shows that ‘after 250 years of independence, inhabitants of one of the most technologically advanced societies in the world rank highest their ability to get their rubbish taken away’.

Given the range of dimensions of wellbeing, what kind of structure would be meaningful as a framework for happiness policy? In Happiness Explained, Anand offers four underlying principles that apply at different ages and in different contexts: fairness; autonomy for ourselves and those we care about; community; and engagement in forms of participation in a range of activities. The profoundly social nature of these underlying principles is striking. Indeed, Happiness Explained notes that the absence of these principles from lived experience should be a cause for concern for public policy as much as it is for the lives of families. One example of this is Anand’s analysis of the principle of autonomy in later life, where loneliness and isolation amongst an ageing population is emerging as a serious and complex problem to solve.

Happiness Explained does sterling work in opening up and structuring wide-ranging literature on subjective wellbeing, drawing on economic studies, psychological research and philosophy in its modest 150 pages. There are occasions when this generalist reader felt as if he was at risk of missing the wood for the trees. In the important discussion of how game theory might explain why, in some contexts, we end up with wellbeing outcomes we did not intend or plan for, Happiness Explained manages to name-check John Nash, Robert Putnam’s work on social capital and Homer’s Odyssey in a three-page dash.

The four key principles of Happiness Explained – fairness, autonomy, community and engagement – are offered as the fundamental contributors to happiness and wellbeing throughout life. However, Anand also acknowledges that the same principles ‘may also sit at the centre of many potential and actual conflicts’ (117). An accessible and short introduction to the capability approach for understanding wellbeing is not necessarily the place to analyse and resolve these, but the trade-offs and potential conflicts between different principles of wellbeing feel like a significant challenge to deploying this framework for public policy.

For instance, the book’s analysis of the economics of happiness concludes that ‘creating societies that offer productive activity to all […] should surely be high on the list’ (69). Happiness Explained also points to evidence on the negative impact that unemployment has on wellbeing as ‘losses of structured activity, both in terms of appropriate cognitive challenge and social inclusion’ (60). How then could a wellbeing analysis inform a policy trade-off between subsidising fewer, more highly-skilled, structured and paid jobs versus supporting more numerous but less stable and structured employment? If a more sophisticated understanding of subjective wellbeing is to challenge cost-benefit analysis for policy appraisal, it needs to speak to these kind of trade-offs in the resource-limited environments of slow growth or post-growth economies.

Nevertheless, Happiness Explained makes several important observations about the future relationship between research on subjective wellbeing and public policy that hint at areas of future research and analysis, like considering wellbeing from the perspective of market failure. Anand challenges us to bring wellbeing to the heart of analyses of market efficiency. Rather than limiting subjective wellbeing to a list of externalities, one of many results of another party’s choices and decisons, we should treat the lack of focus on wellbeing as a market failure itself and consider how choices and their impact on wellbeing could be presented to citizens in ways that are compelling and relevant to their context.

The sheer breadth of studies referenced in Happiness Explained across economics, social psychology and philosophy may provide sufficient ammunition for those that believe that Sen’s approach to capabilities cannot be developed into an economic index for measurement and analysis. However, this guide does suggest we are getting closer to mapping the territory of wellbeing and developing usable checklists for citizens and policymakers to look beyond narrow outcomes or what appears immediately salient about experiences and interventions.

Jake Eliot is a public policy professional with over ten years of experience in research and policy in a variety of roles in the voluntary and public sector. He is on Twitter @JakeEliot.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments