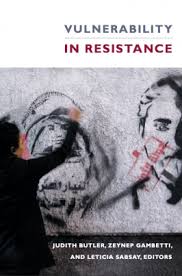

In Vulnerability in Resistance, editors Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti and Leticia Sabsay explore the role of vulnerability in activism, positioning it as a potential tool for resistance. While Chris Waugh questions the volume’s accessibility for those less familiar with its academic jargon and discursive framework, he nonetheless praises the collection for offering diverse and insightful possibilities for radical politics in the contemporary moment.

Vulnerability in Resistance. Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti and Leticia Sabsay (eds). Duke University Press. 2016.

What position does vulnerability occupy in activism? A popular understanding of activism might conceive of activists as those who fight for the vulnerabilised while themselves exhibiting bravery, resilience and determination – qualities that, one would assume, oppose vulnerability. Yet removing or ignoring vulnerability from activism can result in the reserving of activist praxis to a privileged few. In 1984, Félix Guattari offered a searing critique of militancy in the political left. The left militant, for Guattari, was an exclusionary figure, divorced from passion and embodiment, caught in an endless cycle of dogmatic acts and phrases in an attempt to recreate the Leninist breakthrough that saw the Bolsheviks seize power. Activist subjectivity in this sense has no room for weakness, indecision or doubt. In many ways, Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti and Leticia Sabsay’s edited collection, Vulnerability in Resistance, explores models of activism that offer a countermodel to the militant. Drawing on a diverse range of academic and activist knowledge, Vulnerability in Resistance offers a reconceptualisation of the role of vulnerability: an attempt to break with what Butler terms (and Guattari implies is) a ‘masculinist politics’ without heroising vulnerability.

A central concern of the essays in this volume is that of framing: both how individuals frame vulnerability to themselves, but also how it is framed to individuals in neoliberal society. In her introductory essay, Butler considers how vulnerability is framed to individuals as a disempowering character trait. Vulnerability, however, is not simply a matter of ontology, but rather ‘characterises a relation to a field of objects, and passions that impinge on or affect us in some way’. In other words, vulnerability is based on social relations, and can be context contingent. Butler highlights, for example, attempts by men to position themselves as a ‘vulnerable population’ in order to legitimise anti-feminist politics. Connected to this is the idea of resistance to vulnerability; as Butler argues both here and in her earlier work, in minority groups there is sometimes animosity to those who establish themselves as vulnerable. In doing so, this may unwittingly or otherwise buy into paternalistic power structures. Vulnerability is opposed, in this sense, as a political category, even if it is accepted as an ontological or existential one.

Yet vulnerability can also be used as a tool of resistance, whether through nonviolent resistance tactics whereby the body’s vulnerability becomes a powerful political symbol or through the reclamation of public space in the face of police aggression. A strength of the volume is that it explores vulnerability and resistance in spaces and settings often overlooked by scholars of political praxis. Marianne Hirsch, for example, considers her own linguistic and cultural vulnerability as a child of refugees in the USA. Her sense of being ‘misplaced’ (beginning with her inability to pronounce her name in English, and continuing when her search for German language books is almost thwarted by a librarian due to her age) finds a form of resistance in reading classical German texts. Hirsch’s ‘vulnerable times’ explores the harsh unforgivingness of trauma, and how memory might be mobilised for a different purpose. Vulnerability, Hirsch argues, is ‘a radical openness towards surprising possibilities […] a space to work from as opposed to something only to overcome’. Even on a micro level, vulnerability can provide great potential for change.

A notable essay by Sarah Bracke also highlights the political dilemmas within neoliberal universities centred around the use of ‘trigger warnings’. Under neoliberalism, individuals are meant to perform a certain kind of resilience, a practice that Bracke sees as a gendered willingness to engage with what critics of trigger warnings and safe spaces call ‘challenging ideas’, often as a euphemism for something more sinister. The ‘Look I Overcame!’ narrative is juxtaposed with eruptions of vulnerability. Under this scheme of thought, resilience becomes a means for neoliberalism to force its subjects to abandon dreams of achieving security and instead embrace danger as an inevitable feature of life while maintaining a brave face. Bracke’s intervention here is timely and extremely important. Mainstream discussions of safe spaces and trigger warnings on university campuses have been notably one-dimensional, reducing students who seek safe spaces to fragile individuals incapable of coping with the harsh realities of life. While Bracke may not outright speak for safe spaces, she is at least willing to write about them in a way which is less reductionist.

Questions of space and embodiment loom large behind this collection. Originating from discussions at Columbia University and in Istanbul, memories and experiences of the Gezi Park protests and the Occupy movement inform many of the various essays. It is of credit to the editors that the contributions address the subject matter with such diversity and insight. Notable original input also comes from Basak Ertür’s essay on the role of barricades in resistance and Elena Loizidou’s exploration of the role of dreams in political subjectivity. It is furthermore refreshing to see primacy given to writers from outside of the Anglo-European academy.

However, where this volume struggles is that it offers forth an inaccessible radicalism common to much scholarship by left academics. While there are notable attempts to shake up academic stylistics – Hirsch’s essay, for example, blends personal experience with political criticism and artistic musings – overall the chapters are reliant on academic jargon and embedded in social scientific discourse. For a doctoral researcher with an explicit interest in social movements, theories of resistance and activism, it is extremely useful. One might speculate that it would be of less use for a participant in the Gezi Park demonstrations or an Occupy-style movement. This in itself is a shame, as the authors raise a number of new possibilities for thinking about resistance and radical politics at a time when the Left seems incapable of offering a counter-imaginary to xenophobic right-wing populism.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: (teofilo CC BY 2.0).

Find this book:

Find this book: