In The Art of Brutalism: Rescuing Hope from Catastrophe in 1950s Britain, Ben Highmore offers a comprehensive exploration of brutalism as an ethos and sensibility in art in 1950s Britain. This magnificent and handsomely illustrated history undertakes an insightful dissection of both the artistic milieu that inspired these works and the transforming society from which they emerged, writes Conor McCafferty.

The Art of Brutalism: Rescuing Hope from Catastrophe in 1950s Britain. Ben Highmore. Yale University Press. 2017.

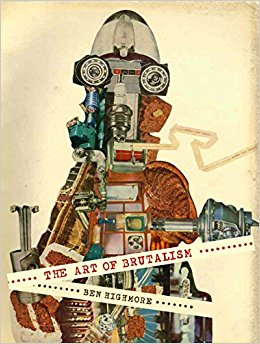

An android, its insides collaged from car parts, domestic appliances and processed food, stares impassively – or is that tilt of the head a sign of curiosity? – from the cover of Ben Highmore’s The Art of Brutalism: Rescuing Hope from Catastrophe in 1950s Britain. This figure is a detail from John McHale’s Machine Made America II (1956), a work that appeared more than 60 years ago on the cover of Architectural Review. It is only the first of many strange faces and bodies to confront the reader in Highmore’s magnificent history of brutalist art.

Highmore’s text weaves between numerous paintings, sculptures and collages in this handsomely illustrated book: these reveal the brutalist fascination with bodies that have been scarred by war and its aftermath, disassembled and reconfigured, foraged from scrapyard junk and forged anew. The artworks are only part of Highmore’s story: he also draws on documentary materials and ephemera in support of his narrative – photographs, exhibition views, domestic and workplace interiors, street scenes, architects’ sketches and manifestoes, advertisements, newspaper clippings and magazine covers. You do not close this book so much as resurface from its dense, all-encompassing visual world.

This book is undoubtedly an in-depth work of art history, but Highmore, Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, is less interested in classifying artworks than in understanding the artistic milieu that animated them and the transforming society from which they emerged. Brutalism appears with a small ‘b’ throughout the book, signalling Highmore’s refusal to engage with the ‘victory narratives’ of art history. (By those terms, brutalism was only ever an inchoate movement that failed to mature before being swallowed by Pop Art.)

Alison and Peter Smithson, the architectural duo who were enthusiastic early adopters of the brutalist designation, feature prominently throughout, as does Eduardo Paolozzi, an artist who would later be more closely associated with Pop Art. The book also finds a brutalist perspective in the street photography of Nigel Henderson and in the startling, pulsating paintings of Magda Cordell. This small group form the core of Highmore’s history, but several supporting characters – William Turnbull, John McHale and Reyner Banham, among other artists, writers and philosophers – make frequent appearances. Aside from moving in the same circles as acquaintances who went to regular salons in each other’s houses, as members of the Independent Group at the ICA and as teachers at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, what was it that connected these artists? Highmore argues that they briefly shared a new ‘ethos and sensibility’ which he identifies as brutalist, even if they only occasionally referred to it as such themselves.

The Swedish architect Hans Asplund’s original coinage, nybrutalism (‘new brutalism’), described a fairly inoffensive house in Uppsala constructed in 1950 of industrial brick. When Asplund’s phrase began circulating among the English avant-garde, it is hard to tell how seriously they took it. In spite of its connotations of unflinching power – and later transformation into a disparaging term reserved specifically for architecture and architects – in the early fifties, brutalism curiously lacked definition. The critic Jonathan Meades notes how ‘[brutalism] was a signifier in search of an object, an -ism that lacked a school or movement or tendency or trend to go with it’.

If there is a central tenet of brutalism, it is nothing to do with a preconceived style – in fact, it seems to involve the determined avoidance of style or label altogether, which makes for a wonderfully diverse selection of works in this book. Brutalism was a way to break loose from the ideological and aesthetic shackles of a previous generation’s avant-garde. For the brutalists, the uniformly white-walled rectilinear buildings of International Modernism and the stylings of the Arts and Craft movement were constraining and stuffy. Highmore shows how these artists engaged instead with the world ‘as found’. They embraced the outpourings of the new mass culture and objects rescued from the junkyard on equal terms with high art culture. They collected and exposed materials that were hidden or ignored, integrating them into their artworks. They valued dramatic, sometimes breath-taking physicality over quiet tastefulness. The brutalists saw their task as ‘making the world anew […] out of the shards of the destructive past’ (147).

The book follows a meandering path, allowing us to examine the group at work in different contexts. As well as showing us individual paintings and sculptures in close detail (as in the wonderful chapter on Cordell’s body paintings and Paolozzi’s ‘Image-breaking, God-making’ sculptures), Highmore is keen to account for the visual world that the group was negotiating, including his scene-setting discussion of the exhibition Parallel of Life and Art, and their production of buildings, crafts and interiors in chapters on the Golden Lane Estate, Hammer Prints and the House of the Future installation.

Parallel of Life and Art was mounted by the Smithsons, Cordell, Henderson and Paolozzi at the ICA in 1953. Later identified by Banham as the locus classicus of brutalism, the exhibition of 122 photographs serves as a useful staging ground for Highmore’s conception of the brutalist ‘ethos and sensibility’. At a time when mass media and popular culture began to produce superabundant imagery, Highmore finds the group grappling with an overwhelming influx of visual materials of all kinds, which they described as ‘material belonging intimately to the background of everyone today’ (33) in their original exhibition proposal. Their first task was to find a way to see these background materials, to ‘[render] a non-conscious visual world as something for conscious and purposeful perception’ (34). Thus, every available surface at the ICA was crowded with ‘a barrage of images’ – artefacts, paintings, prints, aerial photographs, calligraphy – loosely and confusingly categorised. The exhibition intentionally surrounded and disoriented the viewer:

As a demonstration space Parallel of Life and Art taught a different way of looking, one attuned to surface analogies, but open to the vertiginous experience of dramatic shifts in scale and uncanny changes in orientation (44-45).

Highmore argues that this ‘different way of looking’ was in response to post-war devastation. Using a lovely find from the archives, Highmore discusses Henderson’s photographs of the exhibition, in which he has placed his young daughter Justin standing among the images (hers is another face that peers out inquisitively from the pages of the book). ‘Where do you stand’, Highmore asks, ‘to get the world in perspective?’ (56).

Alongside his focus on a group of collaborating acquaintances, Highmore’s dazzling scholarship also brings to life the rapidly changing culture of mid-twentieth-century Britain. Into this world he summons a ‘brutalist subject’, still coping with the effects of the war and austerity and immersed in mass culture, but critically engaging with it. This is where Highmore’s scholarly purpose intersects with the bodies that populate the book’s images. This brutalist subject first figures in Highmore’s chapter on Hammer Prints, a company established by Paolozzi with Nigel and Judith Henderson. Highmore claims that Hammer Prints showed brutalism responding to its historical moment and facing up to a mass-produced society. The brutalist subject was attuned to the modern world and prepared for it by brutalist interiors (107-8). Highmore’s arguments connecting wallpaper print-making with the apocalypse in this chapter are somewhat circuitous, but nevertheless they allow us to take a tour of competing aesthetic and philosophical agendas against the background threat of nuclear war that hung over the era.

For its detractors ‘brutalist’ offers an easy adjective for failed, ugly or otherwise undesirable buildings of the sixties and seventies as well as the architects who had the gall to design them. The term has been rehabilitated in recent years, with several critics celebrating an exuberant audacity that could take masses of exposed concrete and sweep them into hulking, dramatic forms. Highmore insightfully dissects this architectural legacy through the difficult career arc of the Smithsons, finding much to admire, as well as problems to address. But his great contribution lies in his thorough exploration of brutalism as an ethos and sensibility in art and the historical moment in which it offered serious creative potency to his subjects. Re-examining the early careers of artists – some well-known, others less so – Highmore finds them practising and honing their craft and adopting a brutalist outlook that could help them come to terms with the post-war world. Like the children at play on bomb-damaged streets in Henderson’s photographs of Bethnal Green, these artists created endless new forms and found hope among wreckage.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Stone of The Economist Building, London, designed by The Smithsons (seier+seier CC BY 2.0).

Find this book:

Find this book: