In December 1942 the government released a report authored by Sir William Beveridge in which he wrote ‘a revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching.’ His report laid the foundations for Britain’s post-war welfare state, while the world was still at war. LSE Festival Beveridge 2.0 (Mon 19 February – Sat 24 February 2018) offers a week of public engagement activities exploring the ‘Five Giants’ identified by Beveridge in a global 21st-century context.

Running until 13 April 2018, a new exhibition at LSE Library, ‘A Time for Revolutions: Making the Welfare State’, is also taking the 75th anniversary of the release of the Beveridge report as a moment in which to explore the Library’s rich social history holdings and create an exhibition telling some of the history of social welfare in Britain. Here Inderbir Bhullar, exhibition curator, picks out some of the objects and tells the stories contained in the cases.

1). N.W. Grey to J.B. Saunders, 1852, Coll Misc 0699

This letter is from the section of the exhibition which contains the oldest items, dating from the days of the Poor Laws. These laws actually spanned several centuries from early legislation passed in Elizabeth I’s parliament all the way through to the mid-twentieth century. It’s still a surprise for people that the Poor Laws were only officially repealed from the statute book by the 1948 National Assistance Act, marking the end of almost 450 years of provision.

‘Provision’, however, sounds rather generous when we consider the situation faced by John Harris, the subject of this letter sent by the Poor Law Board in 1852. Harris had lost his job and the Board was writing to adjudicate on the issue of his request for poor relief, which depended on his children being taken into a workhouse in exchange. The letter is fairly matter-of-fact and its clinical consideration of this quid pro quo reveals how restricted people’s lives were and the difficulties people have always faced during times of financial hardships. Laws were strict and assurances were few for the majority of labouring people.

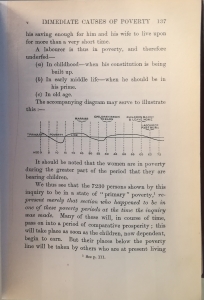

2). Poverty: A Study of Town Life, Seebohm Rowntree, 1902, Main collection books

A couple of years ago I curated an LSE Library exhibition about the Charles Booth study of London life, labour and poverty, of which the most visual and resonant results are the famous poverty maps. The exhibition also touched upon the impact that Booth’s survey had, and this book by Seebohm Rowntree was mentioned.

Rowntree had been influenced by Booth’s methodology and decided to carry out a similar survey in York, which included maps illustrating wealth and poverty in the city. He also uncovered that around 28 per cent of people were living in poverty in York, a number similar to the 30.7 per cent that Booth had found in London, showing that poverty was a nationwide issue. The book is opened to show a small illustration that revealed how poverty and financial difficulties were often faced by people at different points in their lives, whether as children, as parents of newborn infants or as those who had retired with no pension to live on. Both Booth and Rowntree’s surveys helped to remove some of the stigma attached to poverty – the perception that it was necessarily the result of laziness or a ‘moral failure’ – and provided evidence-based analyses of social circumstances, proving that the course of life and labour rarely ran smooth.

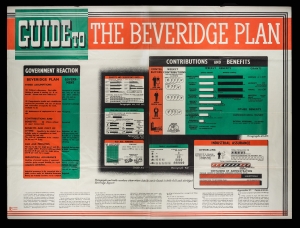

3). Beveridge Plan poster, 1943

This is both the largest and most colourful item on display. With its splashes of colour and graphic flourishes, it was a poster produced in 1943 that illustrated what Beveridge proposed in his recently written report.

This is both the largest and most colourful item on display. With its splashes of colour and graphic flourishes, it was a poster produced in 1943 that illustrated what Beveridge proposed in his recently written report.

The exhibition starts with a look at the Beveridge report and how it came to be written with various hand- or typewritten drafts and pieces of evidence on display. The poster, however, really provides the visitor with a clear answer to who would get what, for how long and why, and also lists the ‘Three Assumptions’ upon which Beveridge’s plans were based: namely, children’s allowances, an NHS and full employment.

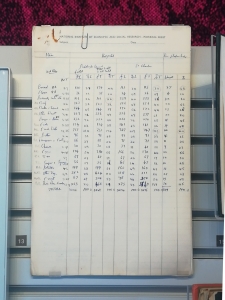

4). Food and drink expenditure at hospitals

The story moves on chronologically from Beveridge and Labour into the 1950s-70s, the so-called golden age of the welfare state and alleged ‘post-war consensus’. However, these terms mask some of the considerable criticisms and disagreements that also inevitably occurred. The handwritten list of expenditure on food and drink from two London hospitals was displayed not only to make people hungry (although maybe the opposite would happen given it was hospital food), but also because it was important evidence gathered by two researchers who would influence social policy at LSE and help shape it more broadly. Brian Abel Smith and Richard Titmuss were invited to provide evidence to the Guillebaud Committee, formed in 1953 by the Conservative government to investigate the cost of the still relatively new NHS, which was thought to be expensive. Evidence from Abel-Smith and Titmuss helped the Committee find that the NHS was efficient in its spending and that inflation was to blame for escalating costs. It also recommended more state spending on health rather than less.

However, other works by Abel-Smith, Titmuss and fellow researcher, Peter Townsend, also went some way in showing how the welfare state was failing to protect the most vulnerable and that many benefits aided the middle classes more than those most in need.

5). The Westwell report, 1981-82

The last 30 years of welfare debates have mainly been framed by ideas of reform and cost. The Westwell report, presented in the final section of the exhibition, is a good encapsulation of some of these. The report is part of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) archive and was written in 1981-82, after the Conservative’s 1979 election win, and aimed at consolidating power throughout the 1980s. The CPS was a think tank which had been formed by Margaret Thatcher and other longstanding Conservatives, which helped to redevelop Conservative strategy and policy with ideas increasingly focused on free market economics and notions of individual responsibility.

Such initiatives contrasted with the welfare state’s more collectivised methods of support and funding and, as can be seen from the document, asked questions about state spending, which echo in contemporary arguments over austerity economics.

The ‘A Time for Revolutions’ exhibition has many more stories and objects which illustrate how support has been provided (and denied) to people in times of need. Documents recounting life centuries ago during the era of the Poor Laws sit near those debating the Universal Credit reforms. Hopefully they all, either individually or collectively, help give the visitor perspectives on what is an ongoing and ever-present debate. The future of welfare and social security is being discussed now at the LSE as part of the Beveridge 2.0 Research Festival, which is running free events all week between Monday 19 February 2018 and Saturday 24 February 2018, with podcasts of many events available afterwards here.

If you want to visit the exhibition and pick out your own favourite objects, then you are more than welcome to do so. A Time for Revolutions: Making the Welfare State is running in LSE Library’s gallery and open daily to all until 13 April 2018.

Note: This feature gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: A Time for Revolutions: Making the Welfare State exhibition, LSE Library, 8 Jan – 13 Apr 2018 (© London School of Economics and Political Science). Images are provided courtesy of LSE Library/the London School of Economics and should not be reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder.