Sister Outsider, written by Audre Lorde, is the book club selection for the 2018 Women of the World (WOW) Festival (7-11 March 2018). In advance of her facilitation of the WOW Book Club discussion at London’s Royal Festival Hall on Sunday 11 March, Tricia Wombell reflects on the influence of Lorde’s work.

This feature is published as part of a March 2018 endeavour, ‘A Month of Our Own: Amplifying Women’s Voices on LSE Review of Books’. If you would like to contribute to the project in this month or beyond, please contact us at Lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

Praise for the Lorde

If you are in certain social media communities on Twitter or Instagram, you will regularly come across perfectly on point motivational and inspiring quotes from Audre Lorde. One of her most shared quotes is ‘Your Silence Will Not Protect You’. It remains prescient given the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter campaigns, which have spotlighted, amongst many issues, the role of the ‘bystander’ throughout all kinds of communities.

The quote comes from ‘The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action’, a paper Lorde presented in Chicago to the Modern Language Association in 1977. In this powerful speech, Lorde describes the focus that came to her in the three weeks while she waited for the results of a lump in her breast. The directness of the words and the themes addressed sharply highlight the clarity with which Lorde saw her life as a Black, lesbian poet, her place in the world and how she intended to work to make a difference through her use of language and speaking the truth, at the same time encouraging others. A key moment is when she explains how her daughter contributed to the creation of the talk by asking her to tell the audience what happens if you don’t speak out:

… you are never really a whole person if you remain silent because there’s always that one little piece inside of you that wants to be spoken out and if you don’t you just get madder and madder.

Lorde has recently been published in the UK for the first time. The book is called Your Silence Will Not Protect You, and offers a selection of her essays, speeches and poems. While I imagine that the social media shares would have played a small part in the decision to finally publish this Lorde collection here, it is also part of an increase in the publication of non-fiction works by BAME authors in the past year. British non-fiction books include The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, and Why I Am No Longer Talking to White People About Race, by Reni Eddo-Lodge. It is Eddo-Lodge’s preface that opens Your Silence Will Not Protect You, paying direct tribute to the influence and inspiration that Lorde’s work has given to her own.

Lorde has recently been published in the UK for the first time. The book is called Your Silence Will Not Protect You, and offers a selection of her essays, speeches and poems. While I imagine that the social media shares would have played a small part in the decision to finally publish this Lorde collection here, it is also part of an increase in the publication of non-fiction works by BAME authors in the past year. British non-fiction books include The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, and Why I Am No Longer Talking to White People About Race, by Reni Eddo-Lodge. It is Eddo-Lodge’s preface that opens Your Silence Will Not Protect You, paying direct tribute to the influence and inspiration that Lorde’s work has given to her own.

Your Silence Will Not Protect You is a fine introduction to Lorde’s essays and poems, but I do hope that the UK reader will also make their way to Sister Outsider, first published in 1984 (reprinted in 2007), the most famous of Lorde’s non-fiction essays and speeches. Most of the Sister Outsider essays are included in the UK book, but the earlier text also includes two pieces of Lorde’s travel writing. The opening essay is called ‘Notes from A Trip to Russia’, and chronicles a 1976 two-week tour of Russia and Uzbekistan, long before the countries of the (former) Soviet Union were as open as they are today. Lorde was hosted by the Union of Soviet Writers to observe their African-Asian Women Writers conference. Her observations of Soviet society are fascinating: she compares Moscow to New York and Tashkent to West Africa, in particular Kumasi in Ghana, with an emphasis on how the markets appear to be so alike. While her interactions with the people provide insight into a tough everyday life, the reader today might find Lorde’s adoration revealing or challenging even, given our current knowledge of Russia and attitudes to people of colour.

The second ‘travel’ essay that closes Sister Outsider is about Grenada, which Lorde visited in the aftermath of the American invasion of 1983. Lorde’s parent’s had left Grenada in the 1920s, and she grew up knowing of it as ‘home’, which is what her mother called it. In the essay, Lorde describes how the smallest nation on earth is savaged by the most powerful. Here she is writing in mourning, setting out why America could not countenance Maurice Bishop’s independent, self-defined Black-run nation in its backyard. No one talks about this now, and I think that everyone who loves the Caribbean should read this particular piece and think a little harder about the state of the other Caribbean nations and their overbearing neighbour. I have been wondering why these two pieces have been left out of the new UK book: I hope that today’s writers will follow Lorde’s lead in Sister Outsider and be given the opportunity to share what they think about wider world issues too.

The second ‘travel’ essay that closes Sister Outsider is about Grenada, which Lorde visited in the aftermath of the American invasion of 1983. Lorde’s parent’s had left Grenada in the 1920s, and she grew up knowing of it as ‘home’, which is what her mother called it. In the essay, Lorde describes how the smallest nation on earth is savaged by the most powerful. Here she is writing in mourning, setting out why America could not countenance Maurice Bishop’s independent, self-defined Black-run nation in its backyard. No one talks about this now, and I think that everyone who loves the Caribbean should read this particular piece and think a little harder about the state of the other Caribbean nations and their overbearing neighbour. I have been wondering why these two pieces have been left out of the new UK book: I hope that today’s writers will follow Lorde’s lead in Sister Outsider and be given the opportunity to share what they think about wider world issues too.

I especially enjoyed reading these particular essays that originally came from the journals that Lorde kept. However, I also appreciate that the reason her work is so popular today is that it is so relevant to the dialogue that we are facing on identity politics and respect for one another. Almost half a century ago, she was succinctly clarifying the meeting points of race, class, sexism and feminism. Lorde was drawing on the impact of what we now know as ‘intersectionality’, before Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw defined it in the 1980s.

Lorde often introduced herself so that there would be no doubt where she was starting from:

As a forty-nine-year-old Black lesbian feminist socialist mother of two, including one boy, and a member of an interracial couple, I usually find myself a part of some group defined as other, deviant, inferior, or just plain wrong (‘Age, Race, Class, and Sex; Women Redefining Difference’, 1980).

In this essay, she goes on to explain how difference is often used to keep people apart, when in fact appreciating and respecting the differences and making more of the things that people have in common are what leads to change and growth. ‘There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives’ (‘Learning from the 60s’, 1982). This is another of the regularly shared Lorde quotes that speaks to the multiple identities that we all have.

Ultimately, Lorde defines survival (and power) as only coming through transformation, and while such growth may be painful, it is through the understanding of another of her much-shared quotes – ‘… the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ (1979) – that the less privileged will be able to determine change.

Many of the pieces in both books are speeches, and Lorde is an unequivocal speaker setting out in lists, for the sake of brevity, particular points that she wants to ensure become her listeners’ ‘takeaways’. She was originally a librarian (Masters in Library Science from Columbia University), and went on to become an English teacher in a university, so often the audiences that she is speaking to are academics. However, it’s notable that she rarely defined herself as an academic. It seems that the personal was far more important than the professional, while she made the most of the platforms that her profile gave her – often as the only woman of colour.

Nor did Lorde shy away from making it known that such groups should have tried harder to make their events more inclusive. Often she also writes piercingly targeted letters to people that she believes should know better. Two examples of this style are ‘An Open Letter to Mary Daly’ (1979) and ‘Sexism: An American Disease in Blackface’ (1979) – the latter a response to an article that argued that Black women should focus on supporting Black politics and consciousness-raising activities rather than establishing the theories and practice of Black feminism. Reading these articles today, you know that Audre Lorde was strong and brave, and that her creative and precise use of language was exquisite, coming as it does from her first love: poetry. You would most definitely want her on your side in an argument. On the other hand, such conversations – between Black and white feminists; Black men and Black women – are still being navigated, and even more publically given social media today.

As a Black woman, I am hyper-aware of accusations of ‘the angry black women’ stereotype that easily come, particularly from those with no understanding of or reflection on how they’ve gained their own privileges, so it was an absolute eye-opener to read ‘Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism’ (1981). In this, Lorde provides a ‘manifesto’ on how to analyse the resulting anger and turn it into a powerful tool. This is an essay that should be part of every leadership development programme for women and people of colour. I would advocate regular reading of Lorde’s work – it is sustenance for the soul.

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

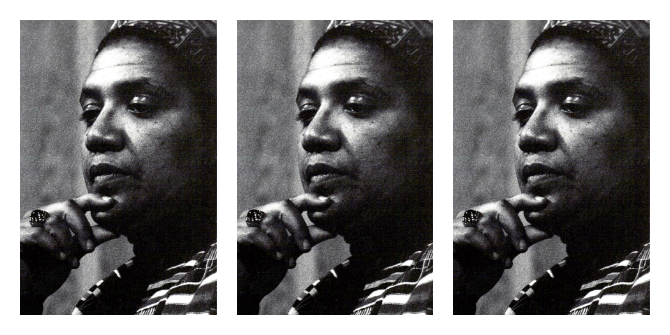

Image Credit: Audre Lorde, Austin, Texas, 1980 (K.Kendall CC BY 2.0).

4 Comments