In Decolonization and Feminisms in Global Teaching and Learning, editors Sara de Jong, Rosalba Icaza and Olivia U. Rutazibwa offer a volume that not only shows how calls to decolonise universities are strengthened when connected to feminist perspectives, but also challenges the individualistic and Eurocentric foundations of many forms of feminism. This is an important contribution to debates on how to decolonise places of teaching and learning, writes Fawzia Mazanderani, positioning critical engagement with feminist theories as integral to this process.

This review is part of a theme week published for International Women’s Day 2019 (#IWD2019), showcasing and celebrating women’s scholarship across the social science and humanities. You can discover more of the week’s content here. You can explore further resources on decolonisation in higher education at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa’s Decolonisation Hub.

Decolonization and Feminisms in Global Teaching and Learning. Sara de Jong, Rosalba Icaza and Olivia U. Rutazibwa (eds). Routledge. 2018.

Over the last few years, calls to ‘decolonise’ the academy have gained momentum, with both students and educators mobilising worldwide to challenge the structures of their universities and their disciplinary canons. These calls for transformation vary widely, from the successful (and unsuccessful) demands to remove statues of colonial oppressors from university campuses, to students recognising that theirs is a largely ‘white’ curriculum, urging them to press for a greater representation of non-European thinkers in their courses. It is within this context that Sara de Jong, Rosalba Icaza and Olivia U. Rutazibwa have edited a highly relevant resource for both educators and learners seeking change within the academy. While varying in terms of their writing style and the context in focus, each contributing author is connected by their argument that calls to decolonise universities, through the re-examination of how knowledge is produced and taught, are strengthened when connected to feminist perspectives.

By forging a connection between decolonial and feminist approaches, the contributors demonstrate how these two broad churches have both sought to move away from the (im)possibility of objective and neutral knowledge production, instead recognising the connection between the personal and political. The editors make a sound justification for the need to incorporate feminisms with decolonialisation, arguing that if everything goes under the umbrella of decolonisation, gender and sexuality may be pushed aside. At the same time, feminist contributions to critical pedagogy often remain focused on the emancipation of the white middle classes rather than recognise the experiences of all women. This volume calls for ‘feminisms’, drawing on an expansive range of international cases, that recognise the different identity intersections of women. By acknowledging the individualistic foundations of many forms of feminism, the contributors demonstrate how we might shift our thinking to be inclusive of communities whose foundational beliefs lie in communal understandings of the world (22). At the same time, the collection demonstrates how feminist theory remains integral to the process of decolonisation, given the gendered and sexualised forms through which colonialism takes place.

To connect this text with the political struggles that inspire it, chapters are interspersed with manifestos and reflection pieces formulated by activists from across the globe. While this is a welcome release from the narrow frameworks of academic expression, venturing outside of circumscribed vocabulary and style can also be challenging, as noted by the editors. It raises questions of what to hold onto, what language to write in and who, ultimately, to please? I found that the more that the contributors veered away from conventional research chapters, the greater the connection made between movements and struggles in and outside of the academy, thus demonstrating the manner in which the identities of ‘educator’, ‘researcher’ and ‘activist’ intersect. By disrupting the conventions of academic expression, these particular contributions provided a freshness and a rawness that rarely sees the light of publication.

The chapters range from personal, and at times slightly whimsical, musings to contributions of a more overtly practical nature. Jess Auerbach’s chapter, which unpicks decolonising strategies adopted by the African Leadership University, stood out as a particularly useful resource for educators seeking ways in which to transform their pedagogy. One take-home suggestion is for educators to draw upon more than just written sources, recognising that Africa’s long intellectual history has only recently begun to be recorded through text. A commitment to assigning non-textual sources of history could, among other things, mean studying artefacts, music, advertising, architecture and food (109). Another strength of the volume is that, by covering such a wide array of country contexts, it gives space to predominantly silenced voices, such as the thinking to have emerged from the Pacific (11).

Yet perhaps the greatest contribution this book has to make is that, if read carefully enough, it forces the reader to make decolonisation a ‘personal journey’, recognising the elements of colonial and patriarchal thinking that they may have inadvertently internalised and reproduced (71). As a teacher who works within a university department that (somewhat) recognises the need to problematise knowledge production, I was reading this book at the same time as teaching about movements to decolonise education. Shortly after one of my seminars, I opened the page to Roselyn Masamha’s ‘Post-it Notes to My Lecturers’ and read her comment on how, when students ‘make ill-informed derogatory comments that reinforce stereotypes, not challenging these suggests collusion’ (147). This was my cue to have a flashback to my own attempts at diplomacy earlier that same day, when I had politely suggested to a student that their view that colonisers had brought ‘logic,’ ‘medicine’ and ‘infrastructure’ to the colonies should be contested. Yet by suggesting that they should be contested, I didn’t contest them with sufficient detail; I simply hoped someone else would. No one did. Are my own nervous desires to cultivate freedom of expression helping to reproduce what I have often discovered to be the racist, and sexist, status quo? I think they probably are, and I am grateful to de Jong, Icaza and Rutazibwa for helping me realise that.

The powerful, yet troubling, recognition that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ (Audre Lorde) raises the question of whether our learning and teaching has been so influenced by an understanding of education as a civilising mission that our curriculums in their current condition cannot be saved; they must be reimagined (100). The question of which tools to use to ‘dismantle the master’s house’ is significant in every contribution of this book. Rutazibwa, who considers the relationship between teaching international development and the survival of the sector itself (158), eloquently addresses this issue. In her chapter, Rutazibwa observes how:

as long as we institutionally keep offering international development studies as a career path that intertwines students’ financial and personal investments, as well as our own careers, it is very unlikely, however critically and pedagogically soundly we engage with coloniality in class, that it will magically dissolve… (158)

While international development is a particularly pertinent example of a discipline that retains echoes of a colonial mentality, Rutazibwa raises a question that applies across disciplines: how much is our research invested in the continuation of the world as it is? She then takes this a step further by asking: how much of our careers are dependent on our deconstructive work only? (172). Rutazibwa’s chapter illustrates how any engagement with the content of our curriculums must also concern itself with the question of whether, in an increasingly neoliberal university, it is possible to garner institutional support to review their foundations.

Like most conversations centred on decolonising knowledges, the nature of the arguments presented in this volume remains often rhetorical, rather than explicitly focused on praxis. It would be valuable if a subsequent publication oriented itself explicitly around the measures that particular institutions or activists groups are taking to decolonise ways of understanding and being in the world. Given the strong link between the extractive industries and colonialism, and the relationship between gender justice and climate justice, an additional publication would be even more valuable if it considered the relationship between the crises that are facing both our ecologies and our academies.

While this collection might have greater impact if it oriented itself more towards practice, it serves as an important contributor to debates concerned with how to decolonise spaces of learning and teaching. Moreover, it raises the important point that discussions regarding decolonisation benefit from an engagement with feminist approaches. For any teacher who has aspirations to transform their own pedagogy, this volume serves as a reminder of how, while the academy has the potential to nourish new ideas, it can equally serve as a space where colonial, patriarchal oppressions are reproduced. As such, any attempt to transform teaching practices cannot occur without continual personal reflection.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

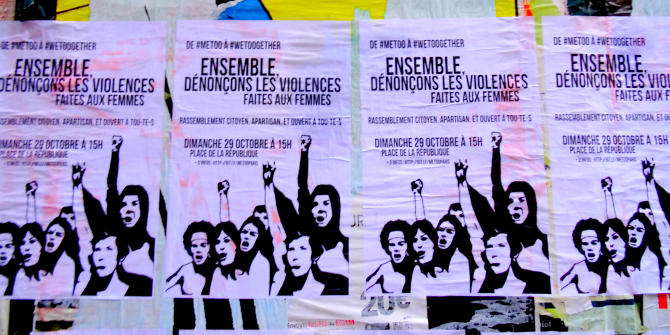

Image Credit: (Alec Perkins CC BY 2.0).

Find this book:

Find this book: