Originally published almost twenty years ago, in Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin author Miguel Abensour confronts the concept of utopia popularised in Thomas More’s 1516 book with Walter Benjamin’s attempt to rescue it from ruin prior to World War Two. In this long read review, Nicolas Schneider examines Abensour’s invitation to understand utopia not as a scheme for a future society but rather as a relational category that functions as an uncanny doubling of present reality.

If you are interested in the subject of this review, you may like to explore a series of LSE RB blog posts on ‘utopia’ published as part of the LSE Literary Festival 2016, celebrating the 500th anniversary of More’s work.

Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin. Miguel Abensour (trans. by Raymond N. MacKenzie). Univocal. 2017.

Find this book:

Find this book:

‘To be done once and for all with the present injustice’ – this is the promise of utopia, at least according to the quote with which Miguel Abensour conjoins the two seemingly disparate parts of Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin. In this book, originally published almost twenty years ago as part of a series of four books on utopia, Abensour sheds light on a tradition of thought first popularised by Thomas More in his homonymous 1516 work. Here, he confronts More’s nascent concept with Walter Benjamin’s attempt, writing on the eve of the Second World War and the Shoah, to rescue it from ruin. The quote, which is from Abensour’s colleague Françoise Proust, stresses the precariousness of utopia: as a promise, there is little in the ‘real’ world that speaks for its possibility.

If engaging with the notion of utopia nowadays seems strangely anachronistic, this need not be to the detriment of the endeavour. Of course, if we follow the usual detractors, the lure of utopia derives from the totalitarian undertow that will swallow whoever falls for its spell. But maybe utopia is precisely the project of developing ways of thinking that reject this Manichaean vision of the world, a world paralysed by a realism that casts its own totalising shadows on everything in its reach. Thus conceived, it provides a powerful tool against a reality that presents itself as ‘without alternatives’.

This, at least, is the invitation extended to us by Abensour in this book: to rethink utopia not as a scheme of a future society that fixes a proper place once and for all, akin to a five-year-plan, but to think it topologically – as a relational category that acquires its analytic power from the ways in which it establishes a distance from the status quo, a distance that, to be sure, is absolute in its aim to depose the present injustice, ‘once and for all’. Utopia, in this sense, rather than hastening the consolidation of some fantasy, works towards the displacement and ultimate destitution of an order that grounds itself in disorder and domination.

Certainly, the contemporary condition seems anything but conducive to a revival of utopia. Instead of mapping out visions for the future of humanity, we are sleepwalking into a disaster – ecological, economic and political – that would eliminate the possibility of making promises altogether. ‘Realism’, being always a realism of the past that denies the possibility of a future in difference from what has been, thus exhausts the conditions of its own existence. Sleepwalking, meanwhile, has become the paradigm of contemporary capitalist realism. It is announced by the ‘new spirit of capitalism’, encouraging everyone to conceive of themselves as entrepreneurs of their own lives. Premised on the successful implementation of the biopolitical dream of individual self-subjection, this spirit invites us to stay on-line, to realise our personal monetary value 24/7 – a paradigm that conquers both spatial and diurnal boundaries.

Always stimulated, never awake – Abensour seizes this paradoxical status quo between sleepwalking and hyperactivity, unmasking realism’s failure to live up to its essential promise: that is, to do away with ambiguity. Feverishly working to postpone the rude awakening that lurks beyond its confines, capitalist realism produces a world that is constitutively contradictory. It is through this narrow but ever-present gate of ambiguity that, Abensour contends, utopia re-enters the stage – as the ambiguous force par excellence.

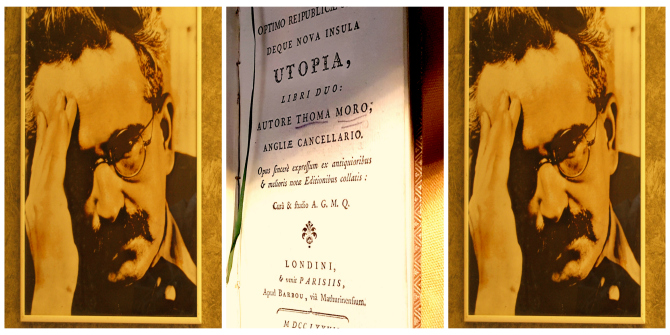

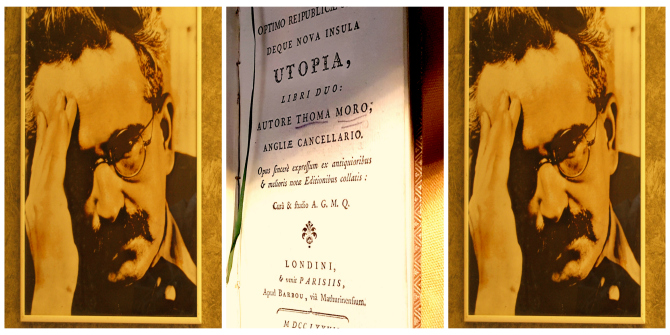

Image Credit: Image of Walter Benjamin (Biblioteca Pública Iu Bohigas de Salt CC BY 2.0)/1777 edition of Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) in the Centre Céramique, Maastricht, the Netherlands (Kleon3 CC BY SA 4.0)

Image Credit: Image of Walter Benjamin (Biblioteca Pública Iu Bohigas de Salt CC BY 2.0)/1777 edition of Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) in the Centre Céramique, Maastricht, the Netherlands (Kleon3 CC BY SA 4.0)

Presenting a subtle and original reading of Thomas More’s Utopia, the first part of the book gauges the scope of this sixteenth-century idea emerging at the threshold of the modern epoch. In Abensour’s reading, ‘Utopia takes on the status of being a true rhetorical invention’, ‘a textual device capable of breaking through the resistances of doxa’ (42). As a rhetorical device, it is geared against the entrenched dogmatic logic of More’s present: in as much as it privileges society over philosophy and practical over theoretical reason, it reaffirms the experiences of people’s everyday lives against the detachedness of the ‘logico-theological authorities’ of the day.

Arguing against both realist and exclusively allegorical readings, Abensour shows how ‘utopian writing’ can be considered as a ‘singular intervention in the field of politics’ (24). It neither depicts a possible reality, nor are its contents to be taken merely metaphorically: what is new about the utopian ‘ductus obliquus’ (41) is its modality, its capacity to become political ‘through the effectuation of the text’ (24). It is the relational character of its enunciations, conceived as a path with sudden turns that never comes out where the realist position would expect it, that invests utopia with its emancipatory power.

This playful art of writing, straddling the boundaries between philosophy and politics, between logic and rhetoric, threatens the status quo precisely because it is impossible to unambiguously identify with either a constative or a poetic gesture. Instead, it applies techniques of disguise and deception, following an oblique path that is equally distant from conservative realism as it is from religious millenarianism. Utopia, conceived topologically, erodes the limits of what is deemed possible under a certain regime of logic – and it is this ‘plasticity’ that Abensour discerns, in the second half of the book, as the conceptual core of utopia that finds its way into the work of Walter Benjamin.

The ‘sentry of dreams’, Benjamin urges us to convey their utopian content into the struggle for emancipation. However – and in these sections Abensour’s analytical rigour reaches its critical apex – if the utopian awakening is to suspend and sublate the waking state that corresponds to capitalist sleepwalking, utopia has to be separated from all myth and fetishisation. This means that the promise of utopia cannot be a blueprint for society or a Platonic ideal state, but the working through of a ‘double movement seizing upon the marks of unreason inscribed within reason, but also grasping hold of the traces of reason present in unreason’ (64).

It is this dialectical imperative that guides Benjamin’s reflections on utopia, based on his correspondence with Theodor Adorno. As Abensour shows, Benjamin, in truly dialectical fashion, both appropriates and defies Adorno’s objections, expressed in a letter that responds to Benjamin’s ‘1935 Exposé’ to the Arcades project. Intensifying the ambiguity of reason and unreason, of progress and regress, of past and future, Benjamin casts utopia as ‘dialectic at a standstill’. In the Benjaminian lexicon, this standstill is linked to the ‘now of recognisability’ (Arcades, N3a, 3) that allows for a glimpse into a different future by way of the construction of a different past: the one that is omitted from official historiography, which, as Benjamin famously states, is written by the victors and which excludes those who have always been oppressed on grounds of their birth, their gender or their lack of means.

This ‘construction-interpretation’ (Abensour, 85) momentarily transmutes utopia from the non-place (u-topos) of ‘realist’ historiography into the possibility of a different, better place (eu-topos). Abensour’s understanding of utopia as a topological notion, drawing on Benjamin, casts it as a primarily relational concept, the constructive impulse of which is shaped in counter-distinction to what the hegemonic common sense declares. This transmutation of utopia would liberate Benjamin’s angel of history and allow him to ‘make whole what has been smashed’ by the course of history, itself ‘one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage’ (On the Concept of History, IX).

The movement that underlies the actualisation of utopia at the intersection of dream and waking state hence turns on a chiasmic inversion of opposites. It is as if the interpenetration of the real with the oneiric left no clear separation between what is possible and what is impossible. History as presented by realism is a phantasmagoria that feeds on the myth of a past unity which propels ‘as much the repetition of catastrophe as the catastrophe of repetition’ (98). In phantasmagoria, appearance and reality are distorted: the old appears as the new, and the new as the old, while the repetition-catastrophe of this vicious spiral remains unthought. Utopia, on the contrary, is the ‘arrest’ (‘Stillstellung’, On the Concept of History, XVII) of the flow of thought that thinking implies.

Utopia is, therefore, an eminently temporal category: as the urge to assemble the unthought contents of the past and to liberate them from oppression by the circularity of phantasmagoria and myth, it points beyond the self-referentiality of the timeless state of affairs. It exposes the regime’s power as grounded in its monopoly on time and of the possibility derived from it. Phantasmagoria stems from a ‘deification of history’ that, as Adorno writes in Negative Dialectics, allowed thinkers from Hobbes and Locke to Hegel and Marx to present their theoretical systems as necessary by positioning them in accordance with some primordial, atemporal state of nature, conceived as negative or positive, respectively. Utopia suspends this time image for the benefit of the now and its recognisability that inheres in every instant.

This striking theoretical development leads Abensour to eventually oppose the realist dogma with the utopian ‘as if’ (101). The thoughts of More and Benjamin, writing at two ends of the trajectory of utopia, are joined in this tension between the force of a logic that wills itself the only legitimate world view and the ambiguity of a rhetorical reappropriation of this same logic. In this refusal to abide by the terms set by realist dogmatism lies the ever-moving point of resistance that ‘the new spirit of utopia’ (15) offers.

Michel Foucault, in a lecture titled Of Other Spaces given in 1967, pursues a similar aim. Crucially, however, he seems to suggests that the notion of utopia has to be given up because it refers to a site ‘with no real place’, opposing to this the notion of ‘heterotopia’, which he describes as ‘a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted’. Foucault goes on to offer an analysis of these heterotopias and the principles that operate them (cemeteries, prisons, brothels, colonies, fairgrounds).

Thus, in a vein to counter the lack of reality that he diagnoses for the concept of utopia, Foucault introduces a notion that is more explicitly topological in that it is defined as a real site within a certain society and therefore relative to other real spaces in this field. However, what he gains by thus detaching a more tangible and therefore possibly more directly political notion, he has to relinquish in ambiguity. The separation between utopia and heterotopia, for all the concretisation of a highly abstract and eventually unreal notion achieved by the shift of prefixes from ou– to hetero-, forecloses the dialectical standstill that can only result from an analysis such as Abensour’s, focusing on the ambiguity of a notion that is, at the same time, both unreal and absolute and constantly on the verge of synthesising into the now of recognisability.

The new spirit of utopia dwells in the topological zone of uncertainty that extends between utopia and heterotopia, pivoting around its realisation in effective enactment or awakening. Identifying the ship as the heterotopia par excellence, Foucault claims that ‘in civilisations without boats, dreams dry up’ (Foucault 1986, 27). This leads back to the beginning of Abensour’s book, in which the adventurer relates what he has seen on the island Utopia: it is not the ship itself that is indispensable for the survival of utopia, but its course, sailing in the winds of realism in order to leave it behind. Utopia doubles reality in a way that is consistently uncanny, precisely because it demands what is, in the words of Françoise Proust, ‘at the same time possible and impossible’.

Nicolas Schneider graduated from LSE’s European Institute with a MSc in European Studies in 2014. He is currently completing a PhD in Philosophy at the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Kingston University, London. Read more by Nicolas Schneider.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:  Image Credit: Image of Walter Benjamin (

Image Credit: Image of Walter Benjamin ( Image Credit: (

Image Credit: (