First conceived by Neil Smith and posthumously completed by colleagues, Revolting New York: How 400 Years of Riot, Rebellion, Uprising and Revolution Shaped a City offers a collection of essays exploring the history of protest in New York City. Without suggesting that riots always have immediate, obvious results, the volume shows the physical and cultural effects that 400 years of rebellion have had on the landscape of the city, writes Sam DiBella.

Revolting New York: How 400 Years of Riot, Rebellion, Uprising and Revolution Shaped a City. Neil Smith and Don Mitchell, with Erin Siodmak, Jenjoy Roybal, Marnie Brady and Brendan P. O’Malley (eds). University of Georgia Press. 2018.

Like any city, New York overflows with alternate histories. After Occupy Wall Street and the flood of protests around the 2016 national election – including citywide marches for Black Lives Matter, the JFK Airport protests and the New School student occupation – New York’s motley history of riots is one well worth visiting. Revolting New York was first conceived by Neil Smith, a CUNY geography professor, and was completed by his students as a collection of essays after his death. At first glance, the book is a representative history of mass political violence in New York. As a project spearheaded by geographers, however, Revolting New York shows the physical and cultural effects that riots have had on the city’s landscape. Smith himself claimed that the uneven development (the ‘production’) of space is an intrinsic aspect of capitalist society, and New York is an exemplary illustration of that principle.

Along those lines, the volume’s lead editor, Don Mitchell, asserts that riots are ‘lightning flashes’ that illuminate ambiguous relationships and social currents that solidify during conflict. Riots are not unruly chaos; rather, the editors argue that through them:

we can see in whose interest the landscape is built and what happens to those who must necessarily be part of it (slaves, working people, immigrants, many women) but who are excluded from its formal mechanisms of power (2).

Those electrifying moments reveal a city’s geography of power, and the realisations they provoke remake that geography into new forms.

Amanda Huron and Raymond Pettit begin Revolting New York with the Dutch traders who claimed land from local Munsee tribes by the Hudson river (originally called the Muhheakantuck) to form New Amsterdam. For colonial New York, the authors show rioting as a carnivalesque, ritualised affair: a temporary suspension of norms that eases social strains and prevents a complete revolution in culture or politics: ‘People acted out fantasies, told moral stories, and played out preferred political outcomes […] Rioting was a safety valve’ (44). Law enforcement was not so formalised in the young United States, and its allegiances and interventions were uncertain. The police were so disorganised and ‘ritual’ riots so established that the 1800s are dotted with protests over worker’s rights or against the aristocracy that held the city hostage for days.

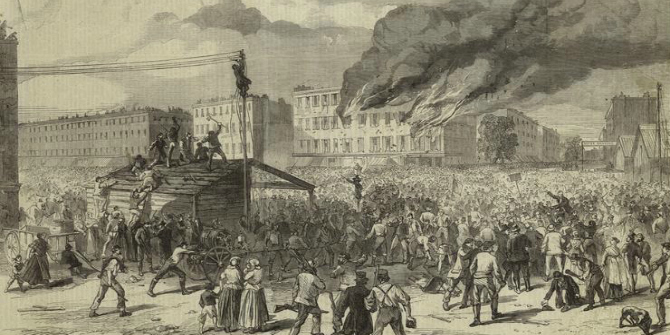

But carnivalesque does not mean peaceful – many early New York riots were slave revolts or their ensuing backlashes, which forged New York’s oft-unmentioned history of race riots. In 1863, for example, growing anger over the American Civil War sparked the infamous Draft Riots. Protesters held a strike against new draft lotteries that escalated into arson, assault and the murder of black New Yorkers in the city streets. That same riot inspired reform of building standards and fire departments, but it also began, as chapter authors Rachel Goffe and Esteban Kelly suggest, ‘the conscription of New York’s ethnic Europeans into an expanded white identity – a project that would consume the city for the next hundred years’ (101).

Image Credit: ‘The Riots in New York: The Mob Burning the Provost Marshal’s Office’, 1863 (New York Public Library, Public Domain)

Image Credit: ‘The Riots in New York: The Mob Burning the Provost Marshal’s Office’, 1863 (New York Public Library, Public Domain)

After the Draft Riots, the norms of mob action shifted, and the city no longer viewed raucous public protest as legitimate. Beginning in the late 1800s, Revolting New York also documents many ‘police riots’, where New York metropolitan police resorted to disorderly violence for fear of losing control in the streets. Police riots particularly merit mention in Revolting New York as moments where police or activists have tried to redefine what is appropriate for political expression in public. Even the rumour of political action has been enough to spur on authoritarian crackdowns: reports from the Paris Commune and its potential influence on an upcoming labour demonstration incited the January 1874 police riots in Tompkins Square – a cautionary tale for all of us in the age of misinformation. With the formalisation of the New York Police Department (NYPD), their growing anti-labour bent also became clear. As Smith writes: ‘the police represented not so much a neutral body devoted to keeping the peace as an armed arm of the state devoted to protecting class interests already written into law’ (112). The unimpeachable violence of NYPD was entrenched after the 1900 Tenderloin race riot, where cops beat African-American citizens who came to them for protection from white mobs. No officer was indicted.

Around that time, the city government also began consciously reshaping New York’s ‘geography of power’. Only a few years and one mass demonstration of communists after 1874, city engineers planted trees and public amenities so Tompkins Square could become Tompkins Square Park. In the 1930s, these park elements were expanded by Robert Moses, further cementing the park in its new role as a ‘place of leisure and recreation, no longer a space for dissent’ (113). This was only a partially successful project – the park hosted anti-war and anti-gentrification actions in the 1960s and 1980s, and it is still a gathering place for yearly Mayday protests today.

The twentieth century brought a rising tide of radical left groups and unions as industrialisation and urban poverty galvanised workers to organise amidst disasters like the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. For them, the street was still a valid venue for political action. During the Depression, communist groups planned ‘unevictions’, pulling personal belongings strewn into the streets by landlords back into apartments and homes. Later, groups like the Black Panthers and the Young Lords filled the vacuum left by the city under its ‘planned shrinkage’ policy during New York’s fiscal crisis in the 1970s. Miguelina Rodriguez describes that era of New York geography as pockmarked by ‘antilandscapes’, a term used David Nye and Sarah Elkind in their 2014 book, The Anti-Landscape, to mean ‘spaces that do not sustain life’ (see Andrew Ross’s review).

The 1990s and early 2000s brought renewed struggle as the revitalised city attempted to quash organised spaces, like community gardens, and World Trade Organisation summits drew out mass protests against globalisation. Learning from the Seattle WTO protests, New York police began to employ ‘Miami model’ tactics – pre-emptive arrests, mass surveillance, command-and-control deployment – for reining in protests. (The 2015 report, Suppressing Protest, analyses this approach’s effect on Occupy Wall Street.) These harsh measures forced activists to use different tactics as well, like Reclaim the Street’s raucous street party in the Lower East Side and Occupy’s relief work following Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

The editors of Revolting New York do not insist that riots have immediate radical results – the book is full of disorganised riots, police riots, ‘ritual’ riots that serve to consolidate power at the top or dispel political energy. Their overarching thesis on the space ‘produced’ by riots is unfortunately hampered, however, by the structure of the book. Each section does discuss New York’s general history, but it feels inadequately interstitial, especially for any causes or effects that are riots. As Mitchell admitted in an interview:

The danger in writing the history of a city through protest is that we miss all the organizing that goes into a moment of unrest, and we miss the day-to-day politics that are just as important in shaping a city.

And even where Revolting New York demonstrates connections between riots, I was sceptical sometimes. In the moment, how many rioters would know or remember that a similar event occurred on the same soil a century and a half before? For the academic, I recommend Revolting New York as a useful reference within those limits, as a ‘helpful distortion’ to complement a more complete history of New York or a unified theory of protest (like Zeynep Tufekci’s recent Twitter and Teargas).

That said, while living in the NYC neighbourhood of Crown Heights, I had immense use for Revolting New York as a guide. In its text, I followed the echoes of 1917 Gary Plan student riots to the later Ocean-Hill–Brownsville strikes by the New York City’s United Federation of Teachers in 1968. Accusations of anti-Semitism from the union against local community boards following teacher dismissals led to the splintering of the long-standing Jewish–African-American alliance in central Brooklyn, which in turn fuelled the disastrous results of the 1991 riots in nearby Crown Heights. That splintering is visible today – Crown Heights still has a stark division between its Caribbean-American and Hasidic sections. I had seen the permanent NYPD surveillance posts, facing east on Eastern Parkway outside Lubavitcher headquarters. But the geography alone wouldn’t tell me why.

Sam DiBella is an MSc candidate in Media and Communications at LSE. He studied philosophy of language for his BA at New York University and has worked as a publishing editor for the past several years. His essays and reviews have appeared in Rain Taxi Review of Books, Heterotopias, The Collagist and First Person Scholar, among others. He tweets @prolixpost.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

1 Comments