In Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, Arlie Russell Hochschild explores the ‘deep story’ behind the rise of the Tea Party and Donald Trump in the USA, drawing on close contact with her research subjects over a five-year period of living in Louisiana. While the book may struggle to ultimately explain the origins of this phenomenon, Hochschild’s intense immersion in the field and her use of interconnected research methods make it a valuable contribution to sociological understanding of this topic.

Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. Arlie Russell Hochschild. The New Press. 2018 [2016].

Hands in the Oily Kitchen Sink – on Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in their Own Land

The question of why it is that right-wing politics, especially in their populist and socially detrimental versions, are on the rise in our time seems a rather hard nut to crack for contemporary social scientists. Often enough, answers to this riddle are couched in moralising terms, showing resentment and scorn towards those social groups that actually vote for right-wing political parties. Arlie Hochschild’s recent book, Strangers in their Own Land, which tries to come to grips with this phenomenon in its American variant – that is, the rise of the Tea Party and Donald Trump – refreshingly avoids the moralistic cul-de-sac.

For her study, Hochschild visited and actually lived in a Deep South state (Louisiana) for five years. While doing so, she combined many interconnected in-depth research methods, from focus groups to interviews to participant observation, to build an emerging narrative of the issue at hand. In this she holds true to her earlier method of what might be called intense immersion, as known from works such as The Second Shift or The Time Bind. She thus gets into enduring close contact with her research subjects, who are mostly petit-bourgeois white rural Louisianans, many of whom struggle with problems related to the regional oil drilling industry.

The point is to come to grips with the ‘great paradox’, as Hochschild calls it. It can be shown conclusively that environmental pollution, but also general social distress and suffering, can be traced back causally to powerful, large companies that are under-regulated and therefore can wreak havoc with the rest of society for their own profits. Why, then, do some that are hurt and affected by these politics defend this form of social organisation, or even see it as a sort of panacea? This is not ‘rational’. It takes Hochschild a lot of working at the ‘empathy wall’ – defined as ‘an obstacle to deep understanding of another person, one that can make us feel indifferent or even hostile to those who hold different views or those whose childhood is rooted in different circumstances’ (5) – to carve out something like an answer to this question. This is so because Hochschild recognises the large gap in life-worlds between herself – the liberal Sociology professor from California – and her research protagonists – the rather conservative-minded people of small southern communities.

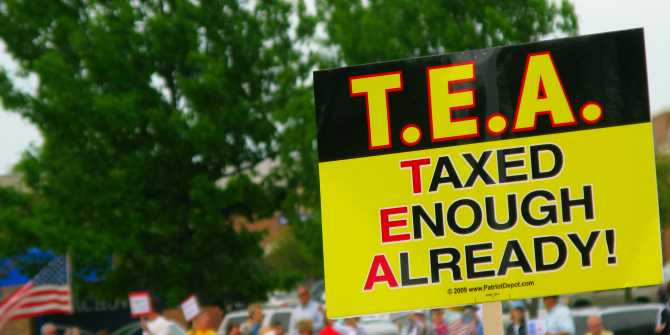

Image Credit: Tea Party demonstration, Texas, 2009 (Susan E. Adams CC BY SA 2.0)

Image Credit: Tea Party demonstration, Texas, 2009 (Susan E. Adams CC BY SA 2.0)

The answer goes like this: these people were brought up with an idea of fair competition and social ascent through hard work and discipline. This hope – to eventually be at the suntrap – vanished through factors both economic and cultural. There was the wage and earnings squeeze of the last decades, rising economic inequality and the belt-tightening this has brought particularly for those groups working in manufacturing and manual jobs. But there has also been the rise of cultural pressure politics of formerly marginalised groups – women, ethnic minorities, the LGTBQ community – that demand recognition in law and political practice.

In the eyes of Hochschild’s protagonists, both of these led to an unfair outcome of the initial competition – not only did they not get what they thought they deserved, but they also experienced other groups ‘cutting in line’. This frustration at the perceived lack of respect for their ideas of fairness, including the scorning of these in the ‘liberal’ press and TV channels, made them feel ‘strangers in their own land’. It prompted them to prefer a nationalistic perspective over, say, a class-struggle one in understanding their situation. The groups found to be responsible seemed to be the ‘liberals’, the Northerners, the Washington government with its regulation frenzy that unfairly skews and perverts fair competition. It created the need to restore what was perceived to be lost – one’s own honourable way of life defined by hard work, fair pay and free decisions. Initial participation in political meetings where the call for extreme economic freedom was coupled with national pride in the ‘American way of life’ created a catalyst effect that tended to feed on and extend itself because of the ‘collective effervescence’: the ‘rebirth’ of collective dignity and pride it fostered and made possible. And so a new, toxic way of doing politics was born.

This is, roughly, how the story goes in Hochschild’s book, and one can clearly see the benefits of her method in the way it makes it possible to explore, see and even to empathise with the ‘anger and mourning’ expressed in these political attitudes and choices. She calls these deep-seated feelings ‘the deep story’ – the emotions of loss and pain that somehow lie behind the almost reflex-like blaming of government regulation for the lack of economic growth and for environmental or social problems. This deep story shows up in variants in the everyday – there is the ‘team player’, who sacrifices herself for a greater good (America) while at the same time denying, in painfully rugged individualist terms, another greater good (rudimentary welfare payments to the most needy). There is the ‘worshipper’, who quenches her doubts in Tea party politics in the opiate of religious dogma and in subordination to her husband. There is the ‘cowboy’ who embraces the dire economic and environmental situation as a welcomed test for ‘masculine’ ‘character’ and ‘stamina’. There is, finally and excitingly, ‘the rebel’ who, disgusted by personal tragedy and hardship, actually starts to develop a more nuanced and emancipated view that starts to signal possible ‘cross-over’ points to more progressive, less socially harmful views. All these are strategies of endurance within adverse living conditions. Furthermore, the part on collective effervescence convincingly makes an anti-deterministic point about the relative autonomy of the sphere of ideas.

But, in the end, the ‘deep story’ still remains a bit of a mystery. Hochschild’s perspective emphasises the dialectic of mutually influencing visions and perspectives on each other’s thoughts and deeds. It shows, so to speak, the main branches of the ‘deep story’, but not the roots. But where does the specific and idiosyncratic vision of fairness and the ‘American Dream’ come from through which these rural white petit bourgeois measure their own and others’ success in the first place? What are its main influencers? Is it class, gender or ethnicity, or a mix of those? How can it all be explained? To be sure, Hochschild presents a historical analogy of the old ‘cotton plantation south’ with the new ‘oil plant south’ – both being, and feeling, subdued by the North, morally put to shame, humiliated, leading to secessionist tendencies of closure. That may be so, but that solves the problem of the roots of the deep story only by shifting it, because the white petit-bourgeois southerners of 1860 are not the same ones of 1960 or 2015. This begs once again the question of what produced their specific vision of the American dream, this peculiar ideal of excellence, in the first place.

But granted, these are difficult questions – it is already an achievement to actually go to the field and to try to put yourself into the shoes of these people, to get your hands dirty in the (oily) kitchen sink. This is so hard for many social scientists, as Hochschild herself notes, because they rarely ever do this with these troubled groups. Hence intellectuals, she admits, must have their ‘deep stories’, too. In that sense, the book is a valuable contribution to the sociological (self-)understanding of a pressing topic of our time.

Tim Winzler is finishing his ESRC-Sociology-pathway-sponsored PhD at Glasgow University. He also studied Sociology at Carleton University, Canada, and at Leipzig University, Germany. His PhD attempts to develop a Bourdieusian-inspired sociology of disciplinary preferences on the example of economics students. Broadly speaking, his research interests lie in the intersection of the fields of the sociology of knowledge, stratification and culture.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

Good review. I just came across references to this book after a recent trip to the oil area of Pennsylvania where I wanted to understand why some many of the poor support the rich (ie Trump and his ilk) and an industry which makes them sick. Not read the book yet but I am certainly interested in doing so. I guess going from this review I will find out some of the detail but not all of the answers..