Asa Cusack takes us on a tour of the best bookshops in Tehran, Iran. If there’s a bookshop that you think other students and academics should visit when undertaking research or visiting a city for a conference, further information about contributing follows this article.

The Best Bookshops in Tehran, Iran

Why go to Iran? Basically because everyone tells you not to. Who could fail to be intrigued by a country rarely presented as anything but an authoritarian Islamic theocracy with a penchant for sectarian proxy wars and uranium enrichment? And how else to find out if the star of George W. Bush’s ‘Axis of Evil’ actually deserves the title?

Being an analyst of Venezuela, another much-maligned foe of the United States, I fully expected to find an Iran quite different from the one I’d been warned about. But really nothing could have prepared me for the overwhelming warmth, generosity, cultivation and latent liberalism of an Iranian people too often conflated with its government. And nowhere is this clearer than in the hundreds of bookshops strewn across the sprawling, modern metropolis of Tehran.

A first surprise was that just about everyone in Iran is able to recite a little classical poetry by the likes of Rumi, Hafez or Omar Khayyam and that just about everyone under 30 in Tehran seems to be a student. The best place to get a sense of this cultural esteem for literature and learning is in the university district on Enghelab Street.

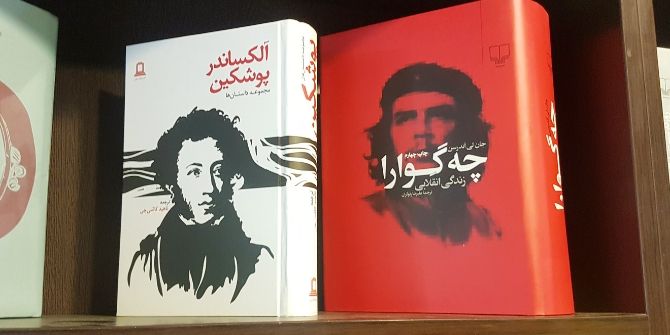

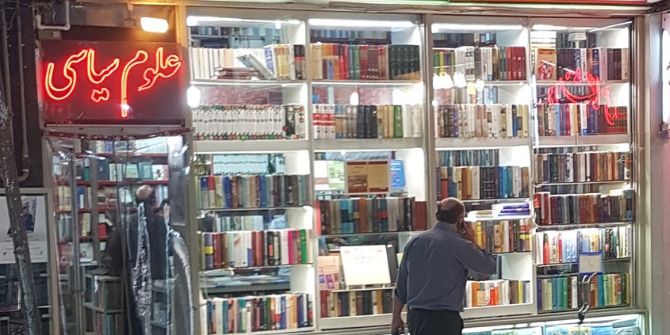

Here, virtually every shop in sight is a bookshop, from generalists with the usual focus on fiction, to specialists in the many academic programmes on offer in the area. Unless you speak Farsi, you’ll be hard-pressed to find much to take away with you, but Engelhab Street is still worth a visit to get a sense of what’s on offer to the locals (see above) – and to see what may well be your first and last book mall (pictured below).

To stand a chance of finding anything in English, however, you will have to head for a branch of Iran’s most popular chain, Book City, which is dotted around the capital. While Central Book City may be the largest, you might also take the chance to swap the chaos of downtown Tehran – we’re talking motorbikes on the pavement – for the relative tranquility of the Niavaran branch.

Nestled in the foothills of the Alborz Mountains that stretch north towards Azerbaijan, Niavaran is one of Tehran’s more affluent and bohemian areas, and it feels a world away from the oil-fuelled expanses of gridlock and flyovers that dominate much of the city. Streets here are tree-lined and shady, and they wind their way up the hill with the same pleasing disregard for planning that we’re used to in London.

But the real star of the show is undoubtedly Tehran’s recently completed Book Garden, an immense and impressive haven for books and book lovers that forms part of a 37-acre cultural oasis constructed right in the heart of the city.

With a total built area of 65,000 square metres, the Book Garden is easily the largest bookshop that I have ever seen, with multiple floors for different readerships, as well as exhibitions, workspaces, cafes and even a cinema.

It is striking from the range of English-language books on offer that while Iran’s theocratic regime may ban alcohol, jail people for dancing and oblige women to wear the hijab, this is something quite different from the out-and-out obscurantism of the Taliban in Afghanistan (who are, of course, theological and political rivals).

Predictably, there are classics by Homer and Euripides, but alongside them sit various works by the likes of Gabriel García Marquez and D.H. Lawrence, either of whom could easily give the censors a palpitation or two.

In part, the explanation can be found in the translations of Rumi and Hafez with which they rub shoulders. Spiritual though these Sufi poets may be, they are also romantic, sensual and dissolute, almost like medieval beatniks:

Suddenly the drunken sweetheart appeared out of my door.

She drank a cup of ruby wine and sat by my side.

Seeing and holding the lockets of her hair

My face became all eyes, and my eyes all hands.

Rumi, Thief of Sleep (translated by Shahram Shiva)

Iran as a state is indeed an authoritarian theocracy, but these are the kinds of poems that form the backbone of Persian popular culture, whether in word or in song, and the private lives of everyday people often seem far removed from the public compulsion to piety.

Exiting the Book Garden, however, brings you back to earth with a bump. The walk up to Shahid Haqqani metro is a strange one, taking you through a vast array of fighter planes, tanks and ballistic missiles belonging to the Islamic Revolution and Holy Defence Museum next door.

For all that the bookshops of Tehran provide an insight into another side of Iran, sadly it looks increasingly likely that the actions of states and their militaries could soon define the nation’s fate once again.

Note: Although I was consistently made to feel welcome and treated with great kindness by local people (as were all of the other travellers I encountered), being Irish may have made a difference. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office currently advises British citizens against all travel to Iran, and anyone considering it should first check the travel advice on the FCO website.

Note: This bookshop guide gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review o Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. Thank you to Asa Cusack for providing the images.

Do you have a favourite bookshop? If there’s a bookshop that you think other students and academics should visit when they’re undertaking research or visiting a city for a conference, then this is your chance to tell us all about it.

As part of a regular feature on LSE Review of Books, we’re asking academics and students to recommend their favourite two or three bookshops in a particular city, with the aim of building an exciting online series for our book-loving community of readers the world over.

Bookshops could be academic, alternative, foreign language, hobby-based, secret or underground institutions, secondhand outlets or connected to a university. We’d like to cover all world regions too.

If something comes to mind, we’re looking for around 150 words per bookshop, detailing why each place is a must-see. Our editorial team can then find suitable photos and links to accompany the piece, though you’re welcome to supply these too. We only ask that you focus on just one city or region, and two or three bookshops within it.

Email us now if you’d like to contribute: lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk

How Humankind Came To Be. Master Li Hongzhi.

“…Since it’s the new year, I should have said a few festive words that everyone likes to hear, but I see danger is getting closer and closer to mankind. Because of this, Gods and Buddhas asked me to tell all beings in the world a few words that the Gods wish to say. Every word reveals heavenly secrets, and the purpose is for people to know the truth and be given another opportunity to be saved.”

***

Why the Creator Seeks to Save All Life

“…The Creator is the Lord of all gods in the cosmic realm, and He is the maker of the Lord of all lords, and the King of all kings. He commands all beings, including all humans, gods, and things in the Three Realms, which He has created. His love is the ultimate holy grace for sentient beings! It is the greatest honor for the world’s people to be loved by Him!”

New articles by Master Li Hongzhi on Minghui website