In this essay, published as part of the LSE RB ‘Materiality of Research’ series examining the material cultures of academic research, reading and writing, Mark Carrigan explores the university office as a site for understanding some of the (unequal) changes to many academic lives during the COVID-19 pandemic and as a hint of what working life might look like when the lockdown is lifted. Who has the space to think? Who is able to retreat from the world? Who can do sustained work without interruption? How can we defend the office in the post-pandemic university, as a place to write and think, while rejecting the inequalities which surround it?

Will we still have offices in the post-pandemic university?

It’s only been a couple of months since lockdown measures were introduced in the UK, yet it feels like it was a different era. A time when we travelled to work, broke for lunch with colleagues (or a rushed sandwich eaten at our desks), before returning home in the evening. At this point it’s a platitude to point to how much life has changed in a matter of weeks, as well as how uncertain our post-pandemic future remains. I’ve nonetheless found myself fixating on my university office as an expression of this change and as a hint of what working life might look like when the lockdown is lifted.

Broadband internet, collaboration platforms and videoconferencing software mean it’s easier than ever to work from home for many, but this doesn’t detract from what a special place the office can be or how bound up it is in our practice of scholarship. The office is defined by ‘the surfaces, spaces and presences that can’t be replicated online and which are vital in creating and communicating ideas and knowledge’. This isn’t just a matter of the resources contained within it but the way in which the arrangement of these resources expresses the work we have done and facilitates (or fails to facilitate) the work we hope to do. It provides a home for our thought, an environment in which it can grow and flourish, even if the mundane reality of this is too often bound up in all manner of contingent frustration. Or so it feels to me when it’s been two months since I last set foot in my office.

I should point out my office is shared with one other person. Though after two years of slowly realising how difficult we find it to concentrate when together in the office, we’ve settled into a routine of mutual avoidance which means that I often enjoy the illusion of a private office for the 2.5 days per week I work in my department. Even in this I am unusual for a postdoctoral researcher, with many of my colleagues in other departments expected to hot desk or share under much less comfortable circumstances. In fact, private offices seem to have become less common across the university system in the twelve years since I began my (part-time) PhD, though I struggled to find a reliable quantification of this observable trend. The fact many offices are under-utilised from management’s perspective helps explain their decline. But the fact academics have tended to have the freedom to choose when and how to use their offices, if they have them, illustrates their significance as an expression of professional autonomy.

In the weeks since I unpacked the office, awkwardly transporting my iMac into a car while petrified of dropping it, I’ve been thinking daily about how these inequalities are reproduced in the locked-down university. The main reason for this is that my iMac now sits on the table in our living room, leaving me perched upon a totally unsuitable chair which gives me back pain if I stay in it for too long. In writing this, I’m aware that my situation could be much more difficult. My partner is another academic who spends much of the working day in the small room which is her workspace; we have no children; and the fact our cat is becoming progressively more vocal when she wants to be fed barely counts as a significant interruption. It’s a much easier and more equitable situation than many people enjoy during the lockdown and I’ve had to remind myself of that when the pining for a return to the office or a quick visit to the university library has left me miserable and dejected.

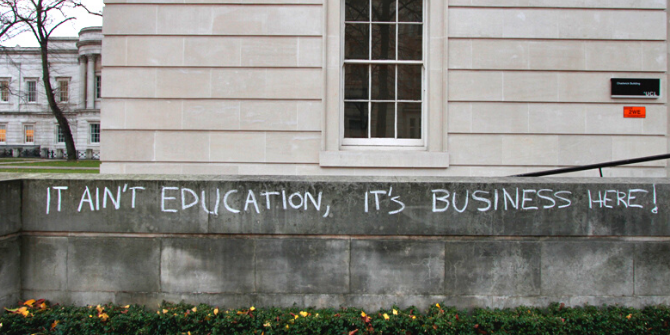

It has still become much more difficult to think deeply or to work for sustained periods without interruption. There’s a cognitive cost to this which shouldn’t be discounted because that momentary effort to return to what you were doing can be depleting when it adds up over the course of the day. But for many people even this will be a luxury, as their domestic arrangements mean it’s unfeasible to have a functioning workspace, even one which might be physically uncomfortable and susceptible to repeated interruptions. Remote working will be one thing for the professor without caring responsibilities ensconced within a luxurious home office and another for their junior colleague sharing the kitchen table with their partner in a one-bedroom flat. It will be one thing for those who live in spacious circumstances with understanding partners, another for those who live with a group of people in a flat share with limited space. It will be one thing for those without caring responsibilities who have more time at their disposal and another for those who are suddenly responsible for homeschooling their children, or other forms of care, on top of their existing responsibilities. There’s a profound inequality latent within what seems on the surface to be the same situation and it’s important we recognise it because the consequences of this will be felt for years to come.

We shouldn’t romanticise the university campus. It’s often a difficult place to work, plagued by the cacophony which inevitably results from thousands of individuals with different schedules running from room to room. It’s often a difficult place to be, unwelcoming for many people in ways which those who, for reasons such as class and race, instinctively feel at home in the university often fail to grasp. But it was a place for work, even if the conditions it provided for the vast majority of us failed to live up to the entrenched stereotype of the professor surrounded by books in the cocoon of a mahogany-and-leather office. Those inhabiting such offices are likely to be able to return to them because this privilege expressed a status which will retain its currency in the post-pandemic university, even if they face a gradual pressure towards downsizing. But for many, office space could become even more scarce in the coming years, ensuring the inequalities of lockdown stay with us even after the current crisis has passed. When managers consider the financial pressures likely to confront the post-pandemic university, the fact that academics have demonstrated a capacity to work from home when the situation warrants it will surely be at the forefront of their response.

This will bring with it a deepening of the inequalities which already exist amongst staff in higher education. Who has the space to think? Who is able to retreat from the world? Who can do sustained work without interruption? An adequate answer to these questions extends far beyond the question of the office, ranging from gendered relations of care through to the hierarchies of academic work and the intersections between them. How can we defend the office, as a place to write and think, while rejecting the inequalities which surround it? The possibility of it slipping away for most of us is a worrying sign of what the post-pandemic university will be like.

The essay gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. If you would like to contribute to the Materiality of Research essay series, please contact the Managing Editor of LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Photo by freddie marriage on Unsplash

1 Comments