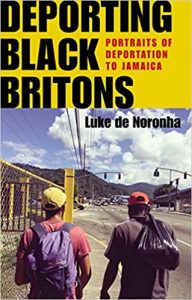

In Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica, Luke de Noronha weaves together the personal histories of four men who have been deported from the UK to Jamaica. Showing how their migratory journeys and experiences have been shaped by state-based racial discrimination and criminalisation, de Noronha explores what these accounts reveal about racism, migration and citizenship in the UK as well as the broader global (im)mobilities regime. Privileging the voices of de Noronha’s interviewees and guided by a strong activist orientation, the book’s persuasive writing style succeeds in offering a vivid depiction of lives impacted by deportation, writes Natalie Dietrich Jones.

Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica. Luke de Noronha. Manchester University Press. 2020.

In Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica, Luke de Noronha weaves the (at times interlocking) personal histories of four men involuntarily returned from the United Kingdom. De Noronha’s objective is to emphasise ‘the connections between punitive criminal justice policies and aggressive immigration restrictions’ in order to ‘develop a more expansive account of state racism’ (4). Through these accounts, and the accompanying theoretical discussion, he offers a twin contribution to Race and Border Studies. It is a timely work in light of the unfolding of the Windrush Scandal, anti-deportation protests and campaigning, the Black Lives Matter movement and a 2019 report by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance in the UK. It adds to a well-established canon, which has seen recent reinvigoration due to the increase in expulsive practices by an example of what Daniel Kanstroom refers to as ‘the deportation nation’.

In Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica, Luke de Noronha weaves the (at times interlocking) personal histories of four men involuntarily returned from the United Kingdom. De Noronha’s objective is to emphasise ‘the connections between punitive criminal justice policies and aggressive immigration restrictions’ in order to ‘develop a more expansive account of state racism’ (4). Through these accounts, and the accompanying theoretical discussion, he offers a twin contribution to Race and Border Studies. It is a timely work in light of the unfolding of the Windrush Scandal, anti-deportation protests and campaigning, the Black Lives Matter movement and a 2019 report by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance in the UK. It adds to a well-established canon, which has seen recent reinvigoration due to the increase in expulsive practices by an example of what Daniel Kanstroom refers to as ‘the deportation nation’.

The book is organised into nine chapters. The Introduction accomplishes several things. It provides an overview of one of the author’s primary field sites, contextualises the study, introduces and qualifies the use of key terms and briefly describes the format of the text. It also positions de Noronha, a UK citizen and a PhD student at the time of the study, in relation to his interviewees. Finally, it also provides a preview to de Noronha’s main concept and argument regarding ‘multi-status’ Britain. This he describes as a nation shaped by an institutionally racist agenda that distinguishes between different categories of citizens and non-citizens. De Noronha understands citizenship as a mode of being which falls outside the parameters of legality. He therefore frames these deported (afro-descended) men – who all immigrated to the UK as minors and, with the exception of one, were all undocumented prior to their incarceration – as Britons. This explains the book’s title.

The introductory chapter is followed by four empirical chapters, which each portray the life histories of Jason, Ricardo, Chris and Denico (two of these names are pseudonyms). To add layers and complexity to these life histories, the narratives of their family members and friends have also been included in these and later chapters. The book does not centre the deportation moment for each of the men discussed; rather, it traces their migratory journeys, which are characterised by exclusion based on experiences of state-based racial discrimination and criminalisation. De Noronha solidly grounds his arguments regarding the extensive reach of the border into migrants’ everyday lives. It is a familiar discourse. He draws on several established scholars such as Nicholas De Genova, Susan Bibler Coutin and Les Back to make his arguments throughout the text. De Noronha’s unique contribution is providing academic analysis of ‘what these stories [of deportation] reveal about racism, migration and citizenship’ (165) in the UK.

The portraits are followed by three sections, which present theoretical arguments concerning hierarchies of non-citizenship (Chapter Six); the racist world order (Chapter Seven); and deportation as foreign policy (Chapter Eight). Together these chapters argue that in Britain, black and brown peoples from formerly colonised places have daily, sometimes violent, encounters with the border. These experiences emphasise their liminal status. Heavily policed, their eventual incarceration sets the stage for their deportation and return to a country they no longer consider home. This expulsion practice is not unique to Britain, which is part of a ‘racist world order’ that continues to be defined by (capitalist) exploitative tendencies. With this argument the research locales are connected to other deporting nations in the global (im)mobilities regime.

In large measure the text privileges the voices of the men interviewed. The book closes with an emotive afterword from Chris. There is extensive use of interview quotations and incorporation of photographs, some taken by the interviewees. This is one of the main strengths of the work, which provides a voice and a degree of agency to an otherwise forgotten and neglected demographic. The second strength relates to its activist orientation and its clear politics. De Noronha proposes that ‘anti-racism becomes necessarily the struggle against immigration controls and citizenship, which fix people in space and in law, and reproduce the racist world order’ (236).

However, there are several key points missing from the text, the inclusion of which would have generated a more nuanced argument. The first is the absence of a gendered perspective of racism and deportation. Given the emphasis on deported men, de Noronha acknowledges this as a potential weakness. Secondly, because he is ‘not concerned with representing ‘‘a culture’’’ (34), he does not delve into a fulsome discussion of the sociology of afro-Caribbean families. For uninitiated readers, this would have explained their fractured nature and the role of migration (and deportation) experiences in alienation. It would also have clarified how household decisions around, and expectations of, migration shaped interviewees’ relationships with their parents and extended family members.

The omission of a discussion on migrant decision-making, including decisions resulting in clandestine migration, is even more glaring, given the unidimensional representation of Jamaica. The island is described as a poor debt-ridden country where ‘almost everyone would ‘‘go foreign’’ if they could’ (75). This is a gross overgeneralisation and oversimplifies the argument by linking migration solely to escapism from poverty. The danger of this view is that it feeds into the very rhetoric of ‘invasion’ of developed nations by the poor that undergirds racist crimmigration policies, which de Noronha criticises throughout the text.

In addition, the book underscores the shortcomings of the outsider gaze. This categorisation is accompanied by implicit and explicit misrepresentations of Jamaica and its communities. For example, the text refers to Harbour View, a mixed working- and middle-class community, as a ‘ghetto area’ (174); here, it is not clear if the term is used by de Noronha or his interviewee, Chris, and the description is left unexamined. Finally, the book does not provide lengthy discussion of the methodology, in particular the challenges of interacting with and reporting narratives of an obviously vulnerable group (deported individuals, some of whom had mental health challenges). This would have been of significant benefit to students engaged in research with similar populations.

Notwithstanding, de Noronha’s descriptive and persuasive writing style succeeds in offering a vivid depiction of lives impacted by deportation. Though grounded in the discipline of Anthropology, the book should be of interest to Sociology, Political Science and Development Studies students and academics. However, the book will also appeal to non-academics, which is the author’s objective. The book’s 318 pages merely scratch the surface of deeply complicated lives. Those who wish to learn more about the individuals with whom de Noronha interacted in Jamaica, via alternative media, may also consult this artistic work.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.