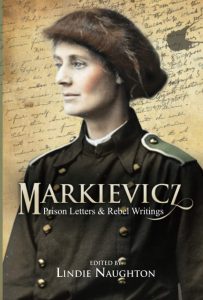

In Markievicz: Prison Letters and Rebel Writings, Lindie Naughton offers a new edition of the collection of letters written by Constance Markievicz, who was a political activist, an Irish revolutionary and the first woman MP. Originally published in the 1930s as The Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, this new edition presents the letters as they were as well as previously unpublished letters, mostly written to friends and family, including her sister, Eva Gore-Booth, during and in between periods of imprisonment. Alongside offering Markievicz’s perspective on early-twentieth-century Irish politics, the collection provides sometimes surprising insight into the interior life of a figure often overshadowed by her controversial reputation, writes Sharon Crozier-De Rosa.

Markievicz: Prison Letters and Rebel Writings. Lindie Naughton (ed.). Merrion Press. 2018.

‘Dearest Old Darling’, Constance Markievicz (1868–1927) wrote to her sister, Eva Gore-Booth, ‘It was such a heaven-sent joy, seeing you. It was a new life, a resurrection, though I knew all the time that you’d try and see me, even though I’d been fighting and you hate it all so and think killing so wrong.’ So begins a series of almost 100 letters between the sisters while Constance was incarcerated in Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison for her leading role in the failed insurrection against British rule in Ireland in April 1916.

‘Dearest Old Darling’, Constance Markievicz (1868–1927) wrote to her sister, Eva Gore-Booth, ‘It was such a heaven-sent joy, seeing you. It was a new life, a resurrection, though I knew all the time that you’d try and see me, even though I’d been fighting and you hate it all so and think killing so wrong.’ So begins a series of almost 100 letters between the sisters while Constance was incarcerated in Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison for her leading role in the failed insurrection against British rule in Ireland in April 1916.

In many ways, this was an unremarkable utterance on the part of a quite remarkable woman to her similarly remarkable sister. Here were two female activists connected by the intimate bonds of sisterhood, as well as by their dedication to intersecting political causes of their time – suffrage and labour being among these. Yet, these were also activists who diverged markedly on the issue of political tactics. Whereas one eschewed violence, the other promoted it.

Constance Markievicz (née Gore-Booth) was born into the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and grew up at her family’s estate in County Sligo on the west coast of Ireland where, among other things, she learnt to hunt. She was presented at the court of Queen Victoria in 1887. Following that, she pursued life as an artist in Paris where she met and later married the Polish writer and artist, Casimir Dunin-Markievicz. After they moved back to Ireland in the early 1900s, Constance, who had already undertaken feminist activism, embraced Irish nationalism and socialism.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, she was renowned as a soldier, as well as a politician. Markievicz trained boys and young men for armed combat, doubtless drawing on her hunting skills. She fought in the failed nationalist uprising in 1916 and was sentenced to be executed; because she was a woman, her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. When Ireland was partitioned into two legislatures in 1922 – Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State – she opposed their legitimacy and continued to agitate for an Irish Republic on the whole island of Ireland. Further revealing the complexities of her values, while she viewed violence as essential in some contexts, she also lamented it in others – as she wrote in a 1922 letter to Eva contained in this volume, the killings in the lead-up to the Irish Civil War (1922-23) were simply ‘awful’.

Violence aside, this was also a woman who was renowned internationally for her pioneering political achievements. She was the first woman ever elected to both the Irish and British parliaments (although she did not take up her seat at Westminster, in alignment with the stance of her party, Sinn Féin), and was the first Minister for Labour in the Irish parliament, the Dáil Éireann. She was also a founding member of Fianna Fáil, successfully standing for parliament in their inaugural campaign.

This series of letters is reprinted in Lindie Naughton’s edited collection, Markievicz: Prison Letters and Rebel Writings, alongside a swathe of others covering numerous periods of Markievicz’s life, some before, but most during and in between, bouts of imprisonment. Indeed, most of the letters were written while Markievicz was in jail – from May 1916 to July 1917 in Mountjoy and Aylesbury, June 1918 to March 1919 in Holloway, June to October 1919 in Cork, September 1920 to July 1921 in Mountjoy and November to December 1923 in the North Dublin Union. What results is a sometimes surprising insight into aspects of the interior life of an iconic figure whose notorious reputation – for example, as a ‘a snob, fraud, show-off, and murderer’– has worked to overshadow the ‘actual’ or ‘real’ woman.

This is not the first time that Markievicz’s letters – most of them to Eva – have been collated and presented to the public. They were first gathered together and published in book form in the 1930s as The Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz by Esther Roper, Eva’s companion. This was re-issued by Virago in the 1980s. In between, the originals were moved about with some being lost. When accessing the letters that had since made their way to the National Library of Ireland, Naughton found that previous published versions of this collection had ‘skirted around some sensitive issues’, as well as left out the names of some people who may still have been alive. This 2018 edition presents the letters as they were (although it does not point out the sections that were previously omitted, which would have presented a fascinating insight into censorship practices and priorities), while also providing updated introductions to each section to contextualise Markievicz’s experiences.

In her introduction to the collection, Naughton asserts that the letters themselves ‘breathe life into the story of one of Irish history’s most fascinating characters, with all her foibles and enthusiasms’. Constance, she writes, was not perfect; rather ‘she could be overbearing and bossy’ (surely accepted, if not lauded, leadership qualities in men). Like many before her, even sympathetic commentators, Naughton almost apologises for Markievicz’s seemingly eccentric nature when there is no need. Indeed, the overwhelming sense that Markievicz’s letters communicate is of a woman who is lonely, self-effacing, practical and stoic, while also indulging in humour and irony – no doubt a mean feat given the deprivations to which she was subject. One passage plucked from a 1924 letter to Eva explaining her feelings about her prison hunger strikes helps exemplify this quiet stoicism and so is worth quoting at length: ‘I always rather dreaded a hunger strike, but when I had to do it I found that, like most things, the worst part of it was looking forward to the possibility of having to do it. I did not suffer at all but just stayed in bed and dozed and tried to prepare myself to leave the world. I was perfectly happy and had no regrets. It is all very odd and I don’t understand it but it was so.’

This collection is an invaluable resource for those keen to explore the emotional and physical experiences of a female revolutionary who, until recent decades of feminist recovery work, was not treated well by history. It offers insight into this activist’s take on early-twentieth-century Irish politics, both enthusiastic and cynical. It allows us to access an imprisoned sisterhood’s concern for each other as harsh conditions took their toll. Perhaps most poignantly, it offers us a rare insight into the intimate relationship between two sisters – both devoted to revolutionising social and political culture – as they navigated the often painful and oppressive consequences of that devotion.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Header image credit: Detail of a bronze statue of Countess Constance Markievicz by Elizabeth McLaughlin (1998) on Townsend Street, Dublin. © O’Dea at Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In-text image: 1954 bust of Countess Markievicz in Saint Stephen’s Green, Dublin (William Murphy CC BY SA 2.0).