In This is What Democracy Looked Like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot, Alicia Yin Cheng provides a concise yet detailed look at the history of the printed electoral ballot in the United States, locating the printed ballot in the development of voting and enfranchisement and offering dozens of visual examples of past electoral ballots drawn from across US history. This timely and relevant work is a worthwhile read and would make an excellent reference book for the shelves of academic and non-academic readers interested in democracy and politics, writes Chris Stafford.

This is What Democracy Looked Like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot. Alicia Yin Cheng. Princeton Architectural Press. 2020.

The printed ballot is one of the most fundamental yet overlooked aspects of democracies throughout the world. Over the course of their lives, the average voter will probably spend just a matter of minutes in the presence of their ballots and perhaps even less time thinking about their finer details. Yet the things we take as given today – the layout, design, wording and even the act of putting an ‘X’ next to one’s preferred candidate – are all relatively new aspects of the ballot and are the result of many years of development and dispute.

The printed ballot is one of the most fundamental yet overlooked aspects of democracies throughout the world. Over the course of their lives, the average voter will probably spend just a matter of minutes in the presence of their ballots and perhaps even less time thinking about their finer details. Yet the things we take as given today – the layout, design, wording and even the act of putting an ‘X’ next to one’s preferred candidate – are all relatively new aspects of the ballot and are the result of many years of development and dispute.

Alicia Yin Cheng’s This is What Democracy Looked Like provides a concise yet detailed look at the history of the printed electoral ballot in the United States. Given the tumultuous aftermath of the 2020 US Presidential election, with outgoing President Trump making unsubstantiated claims of electoral fraud, the recent storming of the US Capitol building by his supporters and Trump’s subsequent impeachment, the book is just as relevant now, if not more so, than when it was initially published last summer.

The book comprises two main sections. The first is a succinct write-up of the history of voting and enfranchisement in the US and how the printed ballot fits into this, discussing the history and development of not just how people could cast their vote, but also who could cast a vote. From highly partisan forms given to voters by the candidates themselves to the more standardised, impartial articles we are familiar with today, the development of the printed ballot is invariably linked to the development of democratic processes and enfranchisement within a nation.

Given Trump’s unfounded claims of electoral fraud, the concise history of how genuine electoral fraud was actually committed in the past proves particularly interesting. The book shows how, as the voting processes developed, so too did the methods by which people would try to cheat the system. The book details various methods of electoral fraud, from rather simple methods such as bribery and intimidation to more ingenious and amusing attempts, such as how the same man could cast multiple votes by entering the polling station in the morning with a full beard and then gradually shaving off certain parts in between repeat trips to the ballot box throughout the day.

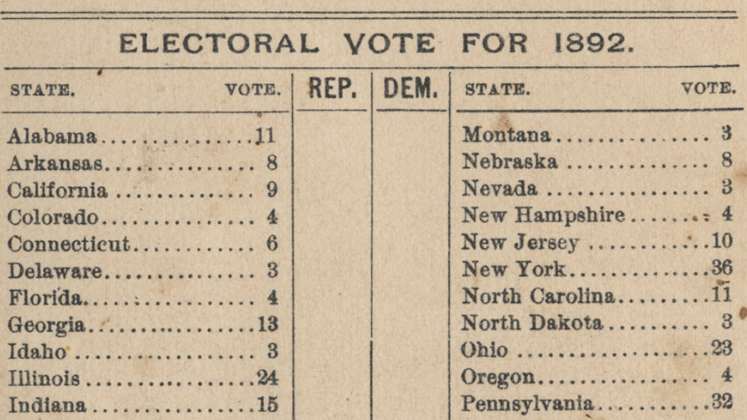

This initial section is very interesting, well written and easy to read, packing a lot of information into a relatively short discussion. It also provides the reader with the necessary background information and context that they will need to fully appreciate the second section of the book. This second section makes up the vast majority of the work and fulfils the promise made by its title in giving a comprehensive visual history of printed electoral ballots in America. These images are accompanied by short descriptions, repeating the information from the earlier section to remind the reader of the specifics of what they are looking at. There are dozens of examples of past electoral ballots covering the breadth of US history and Cheng deserves particular praise for the significant amount of research and archival time it must have taken to find and collate these many examples.

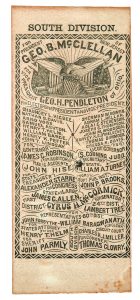

Examples are drawn from the early 1800s right up until the present day. In the early days, the printed ballot was a highly partisan document printed by the political parties and candidates themselves. They were essentially a campaign pamphlet that voters could use to cast their vote. It is striking just how dynamic some of the earlier ballots are compared to the more sanitised ones we are familiar with today. In the early 1800s the monochromatic ballots used varying text fonts and imagery to entice voters, but as printing processes developed, so too did the extravagance of the ballots. By the end of the nineteenth century many ballots could probably be classed as works of art, featuring colourful, patriotic images, creative layouts and swooping text to grab voters’ attention. However, by the early twentieth century, ballots had become the much more standardised, neutral documents we are familiar with today. While this is perhaps for the best, one can’t help but feel a little disappointed with the status quo!

Overall, the two sections of the book complement each other well, although one very minor criticism here would be that the initial textual section could provide better links to the second in certain places. The text regularly discusses various ballots which are subsequently presented in the visual section. Although it is not particularly difficult to cross-relate these, some directions in the text telling the reader where they could find a visual example elsewhere in the book would be a good addition. Additionally, for some of the ballots it is difficult to make out finer details of the text or imagery. However, given the size of some past ballots in relation to the size of the pages of the book, this is understandable. One example from New York in 1902 features the names of 600 candidates and runs to around 14 feet in length, so one can forgive Cheng for not including it at actual size!

This is What Democracy Looked Like does exactly what it sets out to do: provide a visual history of printed election ballots in the US. The textual aspect is brief, but full of detail and easy to follow. As such, this book can be read quite quickly, depending on how deeply one wants to examine the various images of historical ballots. Compared to other works of this nature, this book is relatively inexpensive and within most budgets, although cash-strapped students may want to evaluate if a couple of hours of reading is worth the price of the book. However, for anyone with a keen interest in the issues covered, this is certainly a worthwhile read and would make an excellent reference book on any academic’s shelf. The relative simplicity and accessibility of the book means that it would also lend itself well to non-specialist and non-academic readers. Anyone with a casual interest in politics or democracy could quite easily enjoy this book and learn from it. Given the turbulent political climate in the United States at the time of writing, this book is likely to remain relevant for some time to come.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image One Credit: p. 88. South Division ballot for Democratic presidential electors, 1864. This dense yet precise lithographic ballot is an impressive display of hand-drawn type. (Courtesy The Huntington Library, San Marino, California).

Image Two Credit: p. 117. Administration Union Ticket, Sacramento, California, 1851. The inks on this three-color, double-sided ballot retain a vibrant hue. The artist’s signature is on the back. (Images courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California).