In The New Age of Empire: How Colonialism and Racism Still Rule the World, Kehinde Andrews explores how the intellectual, political and economic frameworks inherited from colonialism are still governing today’s world, resulting in a new age of empire that perpetuates racism, white supremacy and global economic inequalities. This compact and comprehensive book challenges the grand narratives of the Enlightenment, Western linear progress and developmentalism and offers a broader and more complete picture of the continuing problems of racism and the imperial mentality, writes Ayşe Işın Kirenci.

If you are interested in this book review, you can listen to a podcast of author Kehinde Andrews discussing The New Age of Empire at an LSE event held on 27 April 2021.

The New Age of Empire: How Colonialism and Racism Still Rule the World. Kehinde Andrews. Penguin Books. 2021.

In The New Age of Empire: How Colonialism and Racism Still Rule the World, Kehinde Andrews explores the historical sources of present-day racism as well as the topic of underdevelopment in Africa, showing the complicated and deeply entrenched nature of these issues in their socio-historical context. By tracing back through the Enlightenment, colonialism, genocide in the Americas and the Atlantic slave trade, he reveals that the intellectual, political, economic and racial frameworks inherited from the past are still governing today’s world and generating neo-colonialist and post-racial orders. In this respect, Andrews challenges many theories in development studies that ignore the historically embedded nature of underdevelopment in Africa, instead suggesting a historical institutionalist approach with his study.

In The New Age of Empire: How Colonialism and Racism Still Rule the World, Kehinde Andrews explores the historical sources of present-day racism as well as the topic of underdevelopment in Africa, showing the complicated and deeply entrenched nature of these issues in their socio-historical context. By tracing back through the Enlightenment, colonialism, genocide in the Americas and the Atlantic slave trade, he reveals that the intellectual, political, economic and racial frameworks inherited from the past are still governing today’s world and generating neo-colonialist and post-racial orders. In this respect, Andrews challenges many theories in development studies that ignore the historically embedded nature of underdevelopment in Africa, instead suggesting a historical institutionalist approach with his study.

The main axis of the book is predicated on the argument that the West is always seen as a pioneer of all developments in science, industry and politics, while the global and accumulated character of these innovations, the circumstances that provided the equipment to the West to reach its goals and the effects produced are mostly neglected. Andrews emphasises that it was genocide, slavery and colonialism in the Americas and Africa that paved the way for all these revolutions, and that development also contains a contrary element in itself, underdevelopment. In other words, both development and underdevelopment are the products of the very same process. In this context, it would be beneficial to recall Andre Gunder Frank’s approach in his article ‘The Development of Underdevelopment’ (1966), which sees underdevelopment as ‘a historical product of past and continuing economic and other relations between the satellite underdeveloped and now-developed metropolitan countries’.

The New Age of Empire consists of eight chapters: the first half explains the foundations on which ‘the New Age of Empire’ has been founded, while the other half focuses on the rise of the New Age of Empire and the endurance of the imperial mentality, albeit with a new appearance, a changing balance of powers and drawing on additional actors. Thus, Andrews refers to two stages of imperialism, the second one starting after World War Two.

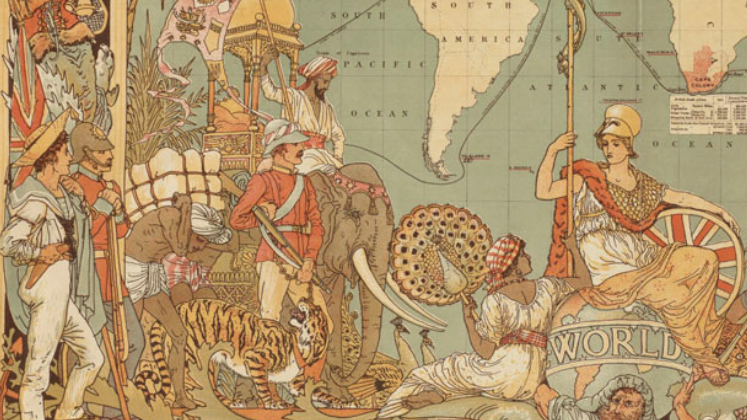

In Chapter One, Andrews expresses the idea that Enlightenment ideals are the intellectual base of the imperial project, which reinforces the idea of white supremacy. This leads to the denial of ‘other’ knowledges produced by non-Westerners and initiates the monopolisation of knowledge by Europeans (1-2). Additionally, it has eased the transition from the old to the new imperialism by means of its supposedly universal and humanitarian values.

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Imperial Federation, map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886’ by Norman B. Leventhal Map Center licensed under CC BY 2.0

Enlightened or not, this imperial discourse can be summed up by the rhetorical question formulated in Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘The English Flag’ (1891): ‘What should they know of England who only England know?’ Kipling’s question implies the importance of having an imperial vision for England and gives it the mission of transcending its political borders. This can give us an insight into the perspectives of the time and is useful in understanding the core arguments revealed in The New Age of Empire as well. Although the poem’s question originally attributed a so-called developmental role to England in colonised areas, it also suggests a wider perspective about the nature of the relationship between the coloniser and colonised. Consequently, to what extent can country- and individual-level analyses give an account of the underdevelopment and development inherited from past colonial relations?

After the intellectual origins of modern-day imperialism are revealed, the book considers the coercive practices which cleared the ground for Enlightenment ideals and originated the first stage of imperialism (24). The second and third chapters of the book focus on how genocide and transatlantic slavery generated European development and, at the same time, African underdevelopment (57). It is precisely these same processes that set forth diverse paths for Europe and Africa.

The expansion into the Americas led to genocide, slavery and colonialism, which enabled Europe to create industrial capitalism and realise the notion of Western development (30-32). In order to eliminate the myth of Western progress grounded on the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, it is necessary to grasp the actions of the West beyond its own borders, as Kipling suggested for different reasons. In addition to uncovering the interrelationship between ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ and the concepts of development and underdevelopment, this vision is also essential to understanding the foundations of today’s rooted racism and the New Age of Empire, as Andrews argues.

Therefore, it becomes relevant to ask about the system that has created systemic underdevelopment for Africa. The main concepts associated with capitalist development, the dispossession of the colonised and accumulation by the colonisers, are basic features of an age that employed genocide and slavery in order to possess lands and dispossess people. Since Andrews relates the sources of underdevelopment in Africa to these dispossessions, genocide, slavery and colonialism, studies that take the sources of underdevelopment as being the lack of proper economic institutions, capitalist relations, civil society and private sector development miss the matter at hand.

After the accumulation and dispossession phases had been completed, the West had control over the means – resources and labour – to claim colonial dominance, as outlined in detail in Chapter Four (89). As a result, racial hierarchies and economic inequalities became more systematised and institutionalised, which complicated the process. Thus, as Andrews points out, linking these problems to the quality of governance and capabilities can lead us to miss the root causes and misevaluate the current system of inequalities and racial discriminations.

As revealed in Chapter Five, Andrews evaluates the transition from the old system of imperialism to the new one as a system update and names it ‘liberal imperialism’ (111-12). The new system with its cooperative institutions embracing Enlightenment ideals, such as humanitarianism and universalism, claims to promote good governance and the liberal economic order in formerly colonised regions. However, it causes the persistence of racial hierarchies and white supremacy by accusing Africans of their own underdevelopment and relating this to the lack of good governance or their so-called tribal way of life (131).

There are many movements defending equal rights for all and the New Left campaigned for social democracy and civil and political rights over the course of the second stage of imperialism. However, realising the systemic nature of the problems of racism and social, economic and political inequalities remains most urgent, as Andrews highlights in Chapter Seven. Due to racism’s institutional and deeply rooted nature, he opts for true revolution uniting Black communities (206). Dismissing metanarratives and myths that blur our understanding of the lasting racism against Black people and the causes of underdevelopment in Africa can be the first step in combatting the anti-Black, post-colonial and post-racial world order.

Overall, The New Age of Empire provides a compact and comprehensive resource for those interested in development and colonialism studies who are looking for more critical perspectives on some of the orthodoxies in the political economy literature. Through its historical institutionalist approach, the study challenges the grand narratives of the Enlightenment, Western linear progress and developmentalism. Also, by emphasising the continuities instead of the ruptures in history, Andrews presents a broader and more complete picture of the problems of racism and the imperial mentality. Although the appearances of imperialism may have changed, the core has been preserved and continuities persist. Producing a transformation depends on us changing our approach and being critical in treating the literature before us.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.