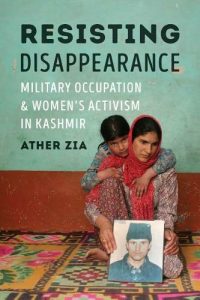

In Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir, Ather Zia explores the everyday resistance of women activists in Kashmir who focus public attention on the Kashmiri men disappeared by government forces. Effectively capturing the agency, memorialisation and resistance of these activists, this poignant and evocative ethnography will be of interest to students and academics working in the fields of anthropology, sociology, gender studies and critical Kashmir studies, finds Aatina Nasir Malik.

Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir. Ather Zia. University of Washington Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Ather Zia’s ethnographic account of the life of Kashmiri women is poignant and evocative, foregrounding everyday life as a political process and agency as a capacity for action that is nuanced. Resisting Disappearance is based on an organisation called the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), which came into being in 1994 to fight the enforced disappearances of Kashmiri men by state forces. Tracing the history of disappearing men and women’s struggles in Kashmir, Zia exemplifies how the experience of Habbeh Khatoon – the fifteenth-century poet’s never-ending search for her husband and struggle against the Mughals who sent her husband, the then indigenous king of Kashmir, into exile – is now manifest in a group of Kashmiri women searching for their men.

The APDP activists are Muslim women from economically marginalised rural classes – half-widows, mothers and sisters of disappeared men who, Zia states, have renounced the gendered rituals of mourning. They mobilise demonstrations, collect documentation, pursue court cases, visit government offices, morgues and prisons alongside holding monthly sit-ins, which are now ritualistic acts of public mourning. It is through this activism – both archival and performative – that these women are making the disappeared appear, or, in other words, visibilising those invisibilised by the government. Here the affective politics and hypervisibility of these women becomes what the author, borrowing from Michel Foucault, refers to as the ‘countermemory’: an alternative to dominant state/official narratives.

This ethnographic work becomes further interesting due to the way Zia refers to her respondents as ethnographic partners or a community rather than as ‘collaborators’, ‘informants’ and ‘interlocuters’, as is the norm in Anthropology. These terms in Kashmir are burdened with politics and used to refer to people who are perceived as traitors who have aided the Indian rule in Kashmir. Secondly, the book is what the author refers to as an ‘intimate ethnography’ where her research community becomes ‘family like’ (19). She further offers her ethnographic poems at the outset of each chapter, crafted from both observation and affect, as what she calls evidence of ethical surfeit – where the ethnographer-poet bears the most honest evidence. This ethnography is therefore a work with dual lenses: one of the trained ethnographer and one of the ethnographer poet, both complementing one another.

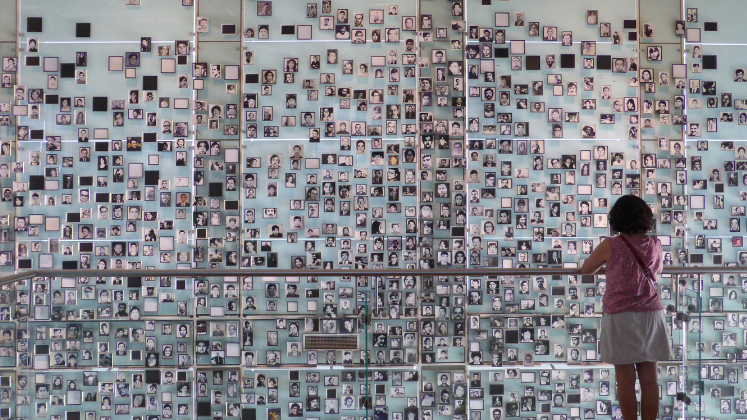

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Women on Steps of Pedestrian Bridge – Srinagar – Jammu & Kashmir – India’ by Adam Jones licensed under CC BY 2.0

Resisting Disappearance is divided into seven chapters, each catering to a different theme. Chapter One talks about the work of mourning as the politics of resistance. It exemplifies how mundane objects like a door get established as a spectral space offering a threshold between life and death where the return of the dead is conjured repeatedly. The chapter further underscores the process of disappearing the disappearance from the official records and hence elucidates the subaltern power of affective law in relation to the sovereign law. Affective law here is the emotional work of mourning that these women do to keep alive the memory of their loved ones in opposition to sovereign law which impedes justice and memorialisation.

Chapter Two traces how elections allow for a ‘politics of democracy’ that extends India’s rule in Kashmir, thwarting the aspirations of Kashmiris. Here the construction of the Kashmiri ‘other’ via material and non-material markers is underscored as well as how such representations are furthered by the media, making the Kashmiri body, which is also the Muslim body, doubly killable under law.

Chapter Three is about spectacular protests and activism. It discusses the centrally located Pratap Park as a site of protest. Activists are allowed to protest, albeit in a controlled environment, but acknowledgment of their concerns and the delivery of justice hardly ever take place. This chapter builds on the life stories of Parveena (the head of the APDP whose son has disappeared) and Sadaf (whose husband has disappeared), where their performative activism through the notion of asal zanan (good woman) offers a counter-spectacle to the disappearances. For their activism these women deploy culturally ideal feminine acts, which helps them do ‘damage control’ to their hypervisibility in public. These women undergo a transformation where they are pushed from the private to the public domain; the justification for this is grounded in the ethics of an asal zanan and sometimes in the elevation of their status in being ‘just a woman’. This helps them sustain both the masculine military regime and the subaltern cultural patriarchy – representing what the author calls a triumph of subalterity within subalterity.

Chapter Four further talks about gendered resistance, establishing Kashmiri masculinity as the non-hegemonic one against the powerful military apparatus. The subservient status of Kashmiri men is reinforced through everyday rituals like showing identity cards to the authorities. Here, women are pushed to the forefront as visible partners in seeking redress. Under the atrocities, the conventions of gender seem to collapse; borrowing from Begoña Aretxaga, the author refers to this as the ‘inversion of tradition’.

Chapter Five concerns militarising humanitarianism, where humanitarian projects stand for warfare and not welfare. This combines with processes of stringent surveillance and the compiling of dossiers on everyone in Kashmir, establishing everyday life as a grey zone where Kashmiris are not left with much choice. Such interventions are to justify the military’s presence in people’s lives, with the author showing, for example, how the mode of ‘conversation’ between the forces and Shabir (who was detained under false charges of being a militant for 28 months) changes from ‘torture’ to ‘medical treatment’ – where he was earlier tortured and then offered so-called medical treatment by the forces.

Chapter Six establishes the papers and documents that APDP members curate over time – as a file, not only as the proof of disappearance, but also to offer a material reality to the disappeared. Such documents become both an affective and physical site where the disappeared are retrieved, and at the same time are made invincible and credible. In such cases where there is no grave, no jail, no First Information Report, an indefinite wait before the law and no proper closure for family members, these files or archives become important both as a countermemory of loss and as subaltern power. But at the same time, these documents become ‘useless’ as they fail to bring any relief or justice. The final chapter takes the example of a wedding and a protest as commemorative practices where a blurring of the boundaries between joy and grief takes place. In weddings and protests, songs about the disappeared turn them into funerals and celebrations respectively. Here too the work of memory is in contrast with the official accounts marked by silence.

Zia’s study effectively captures the everyday struggles of these women activists whose life is caught in a limbo, and yet this liminal space entails agency, memorialisation and resistance. The book has ‘women’s activism’ in its title, but it does not fall short in bringing to light the struggles and experiences of men as well. Apart from being ethnographically rich, I also appreciated it for being very readable despite being so affectively charged. One might find the book replete with the themes of resistance and countermemory, which feature in each chapter, but that very well marks their inevitability in different spaces and performances for the APDP activists. The only thing that could have been done differently would have been to shift the discussion of the history of Kashmir and armed struggle from Chapter Two to the introduction, which would help readers get a better grounding to locate APDP and this rich ethnography from the very beginning. Nonetheless, this book is a useful read for graduates, postgraduates and academics working in the fields of anthropology, sociology, gender studies and critical Kashmir studies.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.