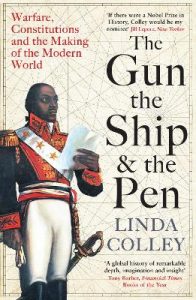

In The Gun, the Ship and the Pen, Linda Colley traces a history of the emergence of constitutions from the 1750s onwards, showing how they developed in tandem with warfare. Meticulously researched and full of eye-opening details, this evocative book is highly recommended by Duncan Green.

The original version of this review was published on From Poverty to Power.

The Gun, the Ship and the Pen: Warfare, Constitutions and the Making of the Modern World. Linda Colley. Profile. 2021.

Holidays are when I tend to read the big heavy tomes – see previous posts on Thomas Piketty, Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace or other random novels.

Holidays are when I tend to read the big heavy tomes – see previous posts on Thomas Piketty, Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace or other random novels.

Last month’s holiday saw me chow down on Linda Colley’s The Gun, the Ship and the Pen, a Big Book with the grandest of sweeps on warfare, constitutions and the making of the modern world.

It’s particularly eye-opening for a Brit. Without a formal written constitution, we mainly come across it in US TV series like The West Wing or when trying to work out why political protests in places like Chile lead to ‘Constituent Assemblies’ to write yet another one. What’s it all about? Linda Colley has a lot of answers.

What is a constitution for? Firstly, a way of (re)imagining a country. But it can also provide proof of modernity to head off the colonialists, a set of guarantees to pacify internal critics or, alternatively, a standard to rally opposition to the existing regime – part driver, part mirror of political, economic and social change. They are infinitely flexible, which explains their political staying power.

Image Credit: Pixabay CC0

Colley takes us through political history from 1750 to the present day through the lens of the appearance and endless rewriting of constitutions. She argues that they arose as the product of ‘hybrid warfare’, combining navies and land armies in a much more militarily effective, but also much more expensive, strategy from the Seven Years’ War in the mid-eighteenth century.

To tax and recruit for this new, amped-up kind of conflict, governments needed to boost their legitimacy with both the public and political/economic elites, and constitutions became a crucial way of doing so. The spread of printing presses and mass literacy also contributed.

What’s striking, given the focus on the US version, is that monarchs, emperors and tyrants were just as likely as democracies to get stuck in. Catherine the Great was a big fan, rising at four in the morning for eighteen months early in her reign to come up with a proto-constitution called the Nakaz.

Colley situates the US discussion, which is sometimes positioned as if it was unique, as actually part of a global surge in interest in constitutions that included China and India, among others. People compared notes, borrowed and hustled their own versions. Everyone was at it, or least men were (there’s a fascinating chapter asking why women, even women leaders, were largely uninterested, with the exception of Catherine).

Most examples of what Colley calls a new ‘political technology’ lasted only a few years; during the heyday, every political nerd was at it. There’s a lovely account of a US constitutionalist beavering away in his Paris lodgings, drafting a new constitution for France (no-one had requested it). Suddenly comes a knock on the door, and a random Parisian asks to present the new constitution he had just drafted for the USA. At which point, the penny drops and the American realises that maybe everyone should stick to drafting constitutions for places they actually know about – a lesson which still escapes neocons and a lot of people in the aid business, alas.

But eccentrics and short life spans don’t seem to have mattered. Constitutions became a crucial viral medium for discussions of politics and how societies should be run – what it was to be a nation. And still are (back to Chile).

Some other interesting things I learned:

- The first recognisable constitution emerged not in Washington, but in Corsica, thanks to Pasquale Paoli.

- The first constitution granting women’s suffrage was not New Zealand but Pitcairn Island in 1838 (not many voters, but still). The book has some interesting thoughts on why the Pacific lent itself to votes for women.

- Simón Bolivar was a big fan of the UK monarchy and House of Lords, and wondered if such a system might work in liberated Latin America.

Like Bolivar, many fighters were also writers, beavering away on draft constitutions when they were not on the battlefield.

Colley is a meticulous historian, with chapters on Pitcairn, Tahiti (another pioneer), Haiti (see the cover), Tunis and Japan as well as more usual suspects. And yes, Britain gets a chapter on whether or not it has a constitution and why it was never written down – there was never a sufficient existential threat, apparently. But Colley also writes well, evoking historical moments and keeping the reader rolling along through the narrative.

Highly recommended.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Banner Image Credit: Photo by Hector Periquin on Unsplash.