Academic success is regularly framed in terms of a particular set of publishing activities that disadvantages women. Katie Wilson and Lucy Montgomery discuss their recent research into how women researchers have pioneered the use of open access and the potential this could have for developing programmes that support more diverse and equitable forms of success for all researchers.

This post was originally published on LSE Impact blog.

COVID-19 has drawn new attention to the challenges faced by academic women across the world. Over the past two years, Twitter hashtags like #momademia, #womeninSTEM and #AcademicWomen have overflowed with words of exhaustion, anxiety and frustration, as women working in higher education and research struggle to cope with the impacts of a global pandemic. Women are using social media to share their worries about the impacts of caring responsibilities on mental health and career progression; to make experiences of insecure work and unrealistic workloads visible; and to question the fairness of systems that privilege narrow measures of ‘excellence’ over meaningful commitments to equity, diversity and inclusion.

The worries that women express about their ability to perform and compete in systems that feel rigged against them are borne out in the academic literature. Women are reported to publish less, have fewer high status authorship positions, are at a citation disadvantage, are awarded less funding and grants, collaborate less internationally and are underrepresented in many scientific disciplines and in senior academic positions. This depressing picture varies somewhat by discipline, but is present in a majority of countries. However, our recent research suggests there are different ways of interpreting and presenting this story.

🎶GIRLS JUST WANNA HAVE FUNding for scientific research 🎤🎵 #academia #WomenInScience pic.twitter.com/lLh2Y6NwTY

— Dr Paz Concha (@pazc) April 14, 2021

There can be no doubt that the challenges faced by academic women are real. However, we wondered whether dominant narratives about ‘research excellence’ and the narrow datasets and approaches used to measure success might also be masking stories about women’s achievements as pioneers and practitioners of open research as well as of the new paths that women are charting for themselves and the institutional changes that can help them to succeed.

Our review of existing research on the relationship between gender and open access (OA) found examples of the ways in which OA publishing is already benefiting women. We found evidence that OA is one of the tools that should be considered when developing strategies for addressing structural disadvantages faced by women in research.

Examples of OA’s positive impact for women include the neutralisation of the gender citation advantage in Political Science through open repositories (Green OA); more elite women researchers selecting open journal publishing (Gold and Hybrid OA), or equivalent to men, providing a positive increase for women’s research output and visibility; mixed women and men authorships publishing more in Gold OA journals; and higher positioning of women in authorship statements (first or last) in open science publications.

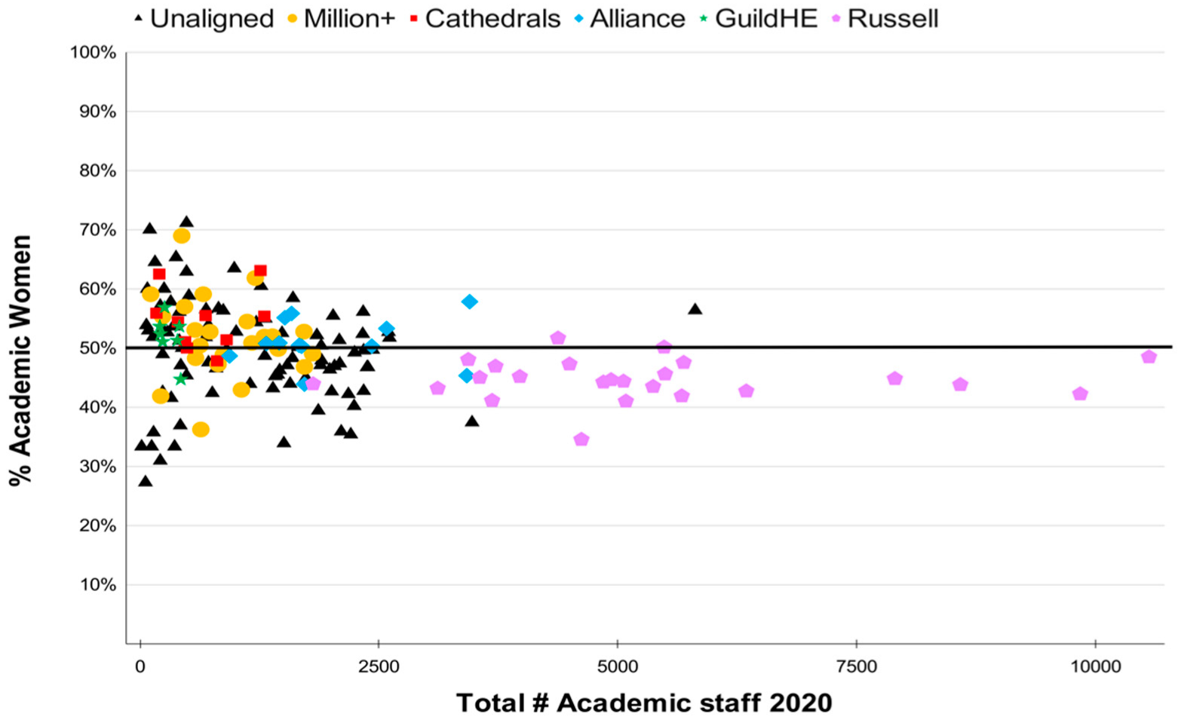

We also explored the relationship between the social and institutional contexts in which women are carrying out research and the ways in which they publish. We used data about the gender makeup of universities in Australia and the United Kingdom as well as data on the proportion of women in academic and non-academic roles, levels of research funding and discipline makeup at each institution. We found a negative correlation between the prestige profile of a university and its proportion of women academics.

Our analysis shows that prestigious institutions, such as the Russell Group in the UK or the Group of Eight (G08) in Australia, favour more traditional research areas and employ fewer women academics than less prestigious institutions. However, institutions with a higher proportion of women in academic roles make more of their publications available in OA and are arguably better at sharing research with the communities that fund and use it.

Percentages of women academic staff (headcount) compared to the total number of academics in the institution for a subset of 165 United Kingdom higher education institutions by grouping, 2020. The full list of institutions and data is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6500293. Data source: UK Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). Image: Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative.

OA has much to offer women: as a strategy for achieving wider visibility for their work, higher citations and greater recognition. Sharing research openly is one step women in academia can take to heighten their scholarly profiles and challenge the publication, promotional and funding practices that continue to impose gender‐blind assumptions. OA may appear a career risk in those disciplines and institutions which encourage or require prestige publications, but circumventing the limitations of pay-walled outputs is one mechanism that women can use to increase the visibility and impact of the work they do.

If higher education and research are to move beyond outdated gender divides towards a future engaged with diverse perspectives, approaches and communities, then the ways in which we approach data about research also needs to change. Rather than focusing on the failure of women to fit within narrow, citation-based definitions of ‘good research’, we also need approaches to data that allow us to understand the characteristics of institutions that support diverse perspectives and experiences as well as the characteristics of institutions that marginalise and exclude them.

In our paper we took a first step: using correlation analysis, rather than traditional bibliometric approaches. By doing this we were able to ask questions about the characteristics of universities and the ways in which women share and publish their work, and to shift our focus away from the types of publications that women may not be producing towards the tools and approaches that they are already using to maximise their impact. This approach to engaging with data has the potential to help universities, funders and policymakers to understand change that needs to happen, and the strategies and infrastructures most likely to deliver it.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, the LSE Impact blog or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Banner Image Credit: Windows via Unsplash.