In December 1941, following the German-led invasion of the Soviet Union, a twelve-year-old Jewish boy named Motl Braverman, along with family members, was uprooted from his Ukrainian hometown to Pechera, the site of a Romanian death camp in which many Jewish people perished. In So They Remember, Maksim Goldenshteyn, Motl’s grandson, uncovers the oft-overlooked history of the Holocaust in the region and its continuing impact on the survivors and their descendants. In this extract published to mark Holocaust Memorial Day, Maksim recounts the moment he uncovered his family’s story and how he found his way into writing the book.

So They Remember: A Jewish Family’s Story of Surviving the Holocaust in Soviet Ukraine. Maksim Goldenshteyn. University of Oklahoma Press. 2022.

My visit began as they usually would, with their chiding me for my choice in outerwear — I came wearing a thin sweatshirt — and for my weekend stubble. I then sat down to the dishes my grandmother had prepared and arranged on her dining table. As we got to talking, I turned to the subject that their daughter Svetlana, my mother, had mentioned to me in passing a week earlier, something about my grandfather’s leading people to safety during the war. The revelation was so startling that I had since forgotten what prompted the conversation. When I looked up from my cucumber and tomato salad, my grandfather had already retrieved a large shoe box from his bedroom. Inside was a manila envelope with assorted newspaper clippings. There was also a thin, yellowing booklet, which he had kept inside a Ziploc bag. He explained that the pages held the stories of Holocaust survivors from Chernivtsi, Ukraine, the city where I was born and where our family had lived before emigrating to the United States as refugees in 1992. He leafed through it and found his picture and an accompanying submission. He proceeded to read all six pages aloud. “The fascists entered and the tragedy began,” he had once written.

My visit began as they usually would, with their chiding me for my choice in outerwear — I came wearing a thin sweatshirt — and for my weekend stubble. I then sat down to the dishes my grandmother had prepared and arranged on her dining table. As we got to talking, I turned to the subject that their daughter Svetlana, my mother, had mentioned to me in passing a week earlier, something about my grandfather’s leading people to safety during the war. The revelation was so startling that I had since forgotten what prompted the conversation. When I looked up from my cucumber and tomato salad, my grandfather had already retrieved a large shoe box from his bedroom. Inside was a manila envelope with assorted newspaper clippings. There was also a thin, yellowing booklet, which he had kept inside a Ziploc bag. He explained that the pages held the stories of Holocaust survivors from Chernivtsi, Ukraine, the city where I was born and where our family had lived before emigrating to the United States as refugees in 1992. He leafed through it and found his picture and an accompanying submission. He proceeded to read all six pages aloud. “The fascists entered and the tragedy began,” he had once written.

My first instinct was to record our conversation. I asked for permission, and he agreed. We spoke for several more hours that same day, he on one end of his couch and me on the other, my phone face-up between us. I came back to hear more on Saturday afternoons for the next few weeks, each time with a notebook and pencil in hand and in a familiar role. At twenty-three years old and now two years out of school, I had already had a brief and unremarkable career as a journalist. Beginning in college, I had written for newspapers across western Washington. My grandfather never approved of my first career choice and constantly harped on my low pay and the dangerous nature of the work (inspired by what he saw on Russian television, no doubt). Still, he stored each of my articles in a folder under his bed. My last reporting job had been at a small daily on Washington State’s Kitsap Peninsula. Now, the story I found myself confronting was that of my own family, a past that had eluded me all these years.

Author Maksim Goldenshteyn

During our interviews, my grandfather spoke with a certain detachment, as if relating someone else’s experiences. Later he assured me that the death camp he survived was never far from his mind. My questions, he said, had rekindled his long-dormant dreams. ‘‘Did I think about it after the war? For all these years I’ve thought about it,’’ he told me. ‘‘How could it have happened? The Germans were a learned people. How could they have taken children and killed them? I can’t understand it.’’ Recently, he had seen a Russian television program about the German liner St. Louis. In 1939, more than nine hundred Jewish refugees boarded it in Hamburg and sailed across the Atlantic, only to be denied asylum – in Cuba, Florida and Canada – and forced back to Europe, where 254 of its passengers later died in the Holocaust. ‘‘We think now, could something like this really happen again?’’ my grandfather said. ‘‘I get scared when I hear people say it. I remember that it really can. I start remembering everything in my head. And right away, I think of these camps and ghettos. It’s frightening.’’

The ideas I had formed about the Holocaust, from books and movies, left me unprepared for what I was hearing. In late 1941, during one of the coldest winters of the twentieth century, nearly every Jewish resident of Tulchyn, my grandfather’s small town in Soviet Ukraine, was sent to a camp in the remote village of Pechera, forcibly marched there on foot. The camp’s originators were not Adolf Hitler’s henchmen but Romanians sent by the dictator Ion Antonescu, Hitler’s Romanian counterpart. The mode of extermination awaiting my grandfather’s family and thousands like them was not Zyklon B but a more ‘‘experimental’’ method, as my grandfather and fellow survivors would often put it: starvation, disease, and exposure. The camp’s setting was not an isolated complex found at the end of a rail spur, as were the Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka killing centers, but the grounds of a former manorial estate in an idyllic village.

The story was full of paradoxes: Ukrainians who both saved and tormented Jews; guards who turned a blind eye to escaping prisoners; escapees who returned to the camp time and time again even after managing to flee. Although seven decades had passed, my grandfather still remembered the precise routes he traveled between villages to beg for food, the number of kilometers separating one village from the next, the names of the guards, the sequencing of key events. With a pencil in his unsteady hand, he sketched the camp’s layout on the back of a blue index card. After the first interviews, I began triangulating these memories against secondary sources. I discovered that a report produced by an international Holocaust commission, formed in 2003 after a series of troubling public statements from the Romanian government and chaired by Auschwitz survivor, author, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel, concluded that Pechera was among the sites of the ‘‘most hideous murders committed against Jews anywhere during the Holocaust.’’ Until now, I had never heard of a place called Pechera, much less that my own grandfather had survived a death camp.

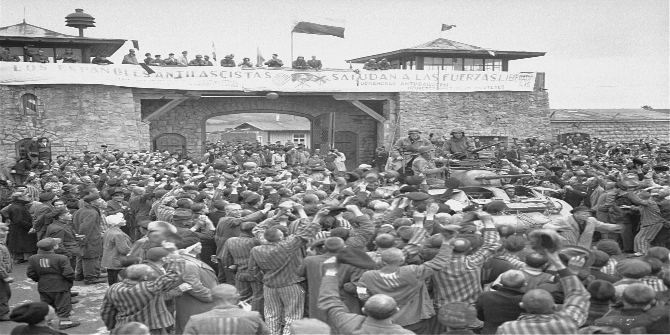

Sitting beside him that spring, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the Liev Schreiber-directed movie Everything is Illuminated, based on the novel by Jonathan Safran Foer. In it, the protagonist, played by Elijah Wood – an eccentric, bespectacled type who is also the author’s namesake – visits Ukraine to plumb the depths of his family’s past only to discover that his late grandfather’s shtetl is long gone. The outcome loosely mirrors the author’s own real-life trip to Ukraine, where he was disappointed to have found ‘‘nothing but nothing.’’ As I would soon learn, the story of Jewish life in my own grandfather’s hometown did not end after the Holocaust, a fate often ascribed to small Eastern European communities with large pre-war Jewish populations. When my grandfather and fellow survivors were liberated by the Red Army, they returned to places like Tulchyn and remained there for decades. Sometimes, they encountered the very camp guards who had so wronged them as children. Yet the memories of 1941-44 were repressed by a government intent on downplaying the singularity of the Jewish wartime experience. In doing so, the Holocaust was erased from public memory.

When survivors could finally begin speaking out during the late Soviet and early post-communist periods, much of the world had already decided what the Holocaust was. As historian Jeffrey Veidlinger notes, survivors who had left their ancestral homelands during the war or in the first years afterward gave the impression that Eastern Europe’s Jewish communities were entirely ‘‘lost’’, that they had ‘’vanished’’, and that they had been ‘’erased’’, as prominent books from second- and third-generation survivors would sometimes suggest. Yet my own family’s story, like those of tens of thousands of survivors who remained behind in Soviet Ukraine, did not fit this narrative.

In summer 2012, my mother and I visited my eighty-five-year-old great-aunt Etel, my grandfather’s older sister, long-since widowed and living alone. She, too, had survived the camp in Pechera. Photos of her son Mitya, her only child, killed in an unexplained military accident at the age of just twenty-one, adorned the walls. Mitya’s death, Etel would explain, was one of the two defining tragedies of her life. At one point, she walked to the middle of her living room to demonstrate the effects of starvation on a teenage body. She imagined the woolen dress she had worn to the death camp, pinched the end of it, and looped it around her waist three times. All these years later, she told us, she still saw German soldiers chasing after her in her sleep. It was strange to be sitting there, chatting and sharing a fruit tart with a woman I had known my entire life – a fixture at holiday gatherings and birthday parties – only to realize that I knew almost nothing about her. ‘‘Well go ahead’’, she said several times that afternoon. ‘’Ask me more questions.’’

Most weeknights that summer, I walked from the office tower where I now worked to the University of Washington’s Suzzallo Library. Under the vaulted ceiling of the famous reading room, I translated and transcribed my interviews, taking notes and highlighting passages. I bought a new backpack to carry the reading material I was now amassing. At home in my spartan apartment, I began listening to testimonies from other survivors interviewed in the late 1990s by the USC Shoah Foundation and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, some of whom, as I would learn, had known my grandfather. I set out to write something – what exactly, I wasn’t sure. Within a couple of weeks, the enormity of this undertaking began to weigh on me. I began to doubt that I was the right person for it, that someone else would be better suited for the work. My trips to the library became less frequent. Weeks away turned into months. At one point, my grandfather asked me what I planned to do with what I had learned. I didn’t have the heart to tell him I had given up.

During the next few years, I focused on my career and started a family. But Pechera was never far from my mind. Only after becoming a new father did I begin to see the stories I had heard, the stories of child survivors, in a new light. I felt a growing responsibility to make sense of what had happened, to preserve a near-forgotten chapter of the Holocaust – or, in the words of scholars Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, to perform a small act of repair. My spark came late one night in early 2017 when I opened the scratchy audio recordings I had avoided since my grandfather Motl’s passing. ‘’You should write this so that no one forgets,’’ I heard him telling me on that Saturday afternoon nearly five years earlier. ‘‘So they remember.’’ With my wife and toddler asleep upstairs, I sat at our dining table until the early-morning hours, listening to his voice. My primitive smartphone had captured the hourly chimes of a wall clock, the din of the TV, and my grandmother Anna’s occasional sighs from the kitchen. Difficult points during his retellings would sometimes end with her asking us to come to the table to eat or for me to translate a new letter that had come in the mail, details I had long forgotten. For the first time, I began to find the words I had been searching for.

Note: This book extract gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Excerpt provided by The University of Oklahoma Press. Thank you to Maksim Goldenshteyn and University of Oklahoma Press for giving permission to publish an edited extract from So They Remember: A Jewish Family’s Story of Surviving the Holocaust in Soviet Ukraine, published in 2022.

Gripping, moving and enticing. I look forward to reading your book.