For the start of Women’s History Month 2023, Sharon Thompson reflects on writing about the Married Women’s Association’s influence on law reform in the mid-20th century in her new book and podcast, Quiet Revolutionaries, and how The Women’s Library archives at LSE informed this research. You can find out more about this project on the Quiet Revolutionaries website.

‘Reform movements are like builders; they set out to erect structures in which human beings can live better lives but there are few of them which can begin their constructive work at once because of the state of the site on which they have to build. This was the position which faced the Married Women’s Association. [The Married Women’s Association] have exposed injustices and absurdities in the legal status of married women […] they have given advice and guidance and won sympathy and publicity for many victimised wives. All this is recorded in the minutes and publications of the Association for the historian to read.’

Speech of Teresa Billington-Greig, MWA Newsletter, June 1958, 7TBG/2/J/08, The Women’s Library

The above extract is from a speech delivered by stalwart of the women’s movement Teresa Billington-Greig to the Married Women’s Association (MWA) in 1958. The speech marked the MWA’s 21st birthday celebrations, and Billington-Greig was their ‘vice-chairman’. Her prescient remark that the MWA’s campaigns were recorded ‘for the historian to read’ is true; these records – including this very speech – are now housed in The Women’s Library at LSE. Billington-Greig’s apparent expectation that future historians will explore the minutes and publications of the MWA also underscores the broader sentiment of her speech, which is that the group’s work was important to histories of the women’s movement and law reform. It might seem peculiar, therefore, that the MWA has been almost entirely absent from these histories.

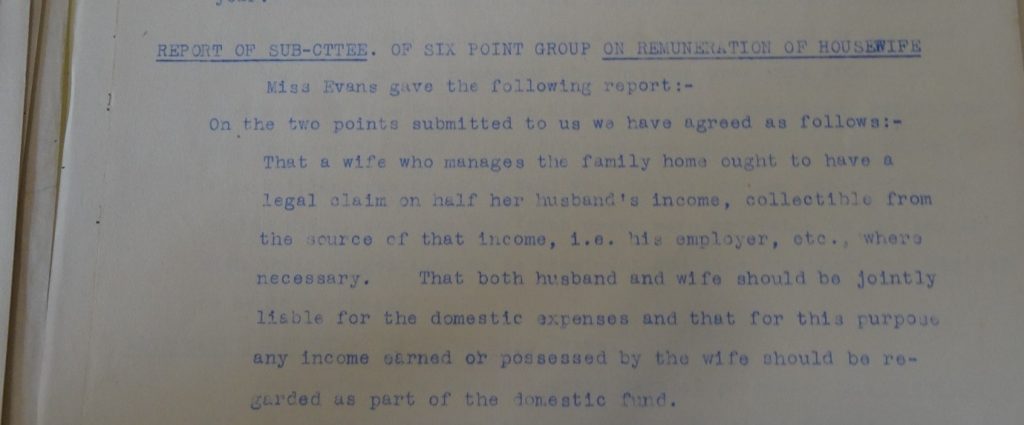

The MWA started out in 1937 as a sub-group of the Six Point Group (SPG), which had been established in 1921 to work on six points that could be achieved by women with the vote at that time. Leading SPG member Dorothy Evans identified the need for the MWA as a group to further the legal status of housewives, even though she was personally opposed to marriage. In her view, the group would be part of a broader initiative to recognise and combat injustice for all women by advocating recognition of the financial value of domestic and reproductive labour. As the below image shows, the SPG set out the ultimate goal of the MWA in a report of an SPG meeting dated 19 April 1937: to give married women property rights during marriage and greater economic power both inside and outside the home as a result.

5SPG/A10/18, The Women’s Library

The MWA was officially established in early 1938 when it became independent from the SPG. It was not based simply upon the idea of a group of married women representing married women; its membership comprised of men and women, married, divorced and single. The group’s members could see that laws defining the status of married women would affect women’s broader emancipation. They could see that the law had failed married women. They could see that something needed to be done. MWA membership included high-profile individuals such as authors Vera Brittain and Dora Russell, Dr Edith Summerskill MP and Helena Normanton, who was the first woman to practise as a barrister. Their campaigns lasted into the 1980s, and ultimately influenced married women’s property rights and reform of divorce and maintenance through their promotion of equal partnership in marriage: a view that was not orthodox as it is in Britain today.

The MWA is remarkable as the first pressure group of the twentieth century to campaign for legal and economic equality of married women as its core focus, because this had important repercussions for the direction of family law reform. In Quiet Revolutionaries, I explore the story of their campaigns, lessons for reform strategies today and how the group’s influence, while subtle, was nevertheless a vital part of how family law came to be as we know it now.

Though my research background is in family law, I was previously unaware of the MWA, because the group is absent from family law textbooks and other accounts of reform. I discovered the group by chance, when I was invited to contribute a chapter to Women’s Legal Landmarks on the Married Women’s Property Act 1964. With little available information about this short, relatively arcane Act, I booked some time in The Women’s Library at LSE. I found that this Act – which gave housewives one share of housekeeping money – was the MWA’s Act. Baroness Edith Summerskill –the peer to have first introduced the Act as a private member’s bill – is credited in some texts. Yet even though the MWA had instigated the Act, and Summerskill had been the MWA’s first president, the Association’s work behind the scenes was never acknowledged in textbooks or legal sources.

There were other examples of the MWA’s unacknowledged impact. The Maintenance Orders Act 1958 – which allowed maintenance payments to be deducted from the husband’s pay cheque – was a replicate of a failed MWA bill from 1957. A private member’s bill that pressurised the government into reforming the financial consequences of divorce in 1970 was inspired by a bill originally drafted by the MWA. However, outside the MWA’s own archives in The Women’s Library, its role in these significant moments of family law history had never been documented.

I was motivated to explore this history in Quiet Revolutionaries because feminists and family law reformers today deserve to know their story, and what it was like for feminist reformers to engage with law reform processes. Like so many others before and after them, members of the MWA had dedicated their lives to improving the lot of women, campaigning ad nauseum for equal partnership in marriage, only to be met with derision, ridicule, wilful ignorance and reactionary backlash. And, after all that, credit for any small breakthroughs was taken away from them and given by a patriarchal narrative to established legislative bodies, or simply credited to the ‘inevitability of progress’. Quiet Revolutionaries sought to challenge and rewrite this narrative, and relied heavily on archival material to do so.

Almost all the archival sources used in Quiet Revolutionaries are housed in The Women’s Library. The documents in these archives include correspondence, files in relation to MWA campaigns, newsletters, pamphlets, conference flyers, reports, handwritten notes, speeches, newspaper clippings and minutes of meetings. As well as the records of the MWA, the book also draws upon the records of individuals and groups integral to the MWA’s story including Teresa Billington-Greig; Helena Normanton; Edith Summerskill; the Six Point Group; and the Council of Married Women. Other primary sources drawn upon from The Women’s Library include Brian Harrison’s interviews on the suffragette and suffragist movements and Michael Summerskill’s interview transcripts, both of which include interviews with MWA members and individuals connected with the Association. These records contain a wealth of information far beyond the scope of my book, waiting for other historians to discover and evaluate them. In addition to The Women’s Library Archives, correspondence relating to the MWA was obtained from The National Archives in London, mostly from the files of the Lord Chancellor’s office and the Law Commission of England and Wales.

There are inevitably gaps in the material generated by the MWA, which posed challenges when uncovering the story of the Association and its members. Two minute books were removed by the MWA in 1988 and have not as yet been returned. Interesting insights scrawled on scrap pieces of paper are undated, and sometimes their context is unclear. Action points are noted in meetings, to follow up on a case, or to announce that an as-yet-unnamed MP will support the MWA’s draft Bill, but incomplete records mean it is often not possible to find out what happened next. Membership records are virtually non-existent, so it is difficult to get a sense of the size of the Association beyond members’ own non-specific accounts. It is also important to bear in mind the subjective nature of these sources, as they could be exaggerated or one-sided. As a result, this material is substantiated in Quiet Revolutionaries by new interview data and secondary sources, both of which help provide a more complete picture of the MWA.

The seven new interviews on which this book is based were undertaken between 2018 and 2020 with friends and family of MWA members. These revealed new information that could not be gleaned from the archives as well as members’ private papers and an unpublished memoir written by Doreen Gorsky, the former MWA Chair. This adds to the published autobiographies of MWA members Edith Summerskill, Dora Russell and Vera Brittain.

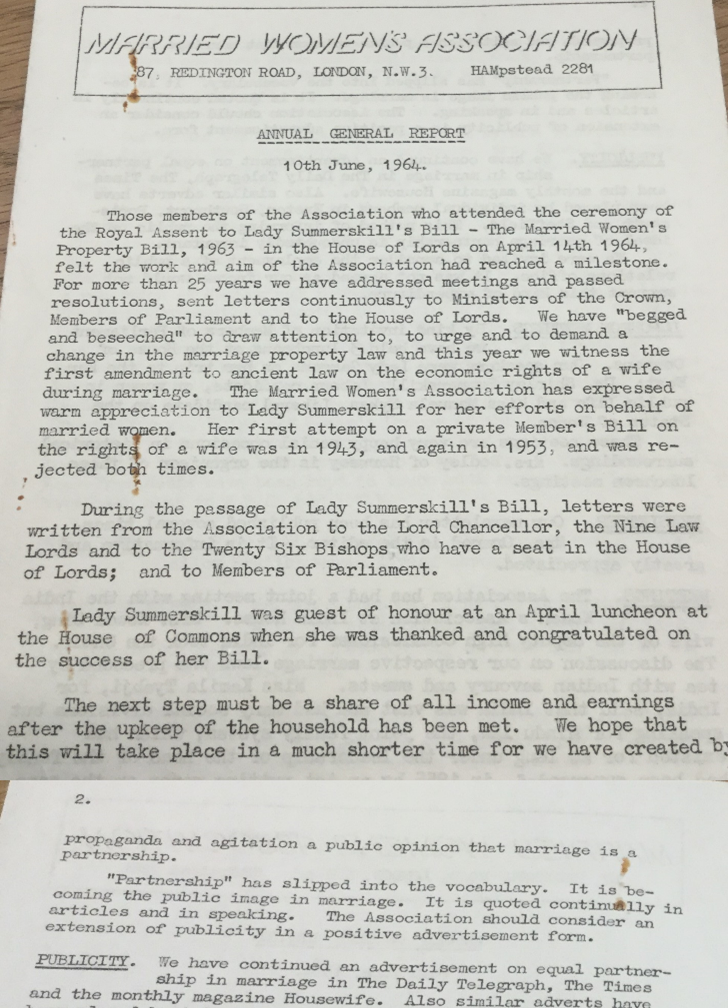

The records of feminist associations within The Women’s Library provide an invaluable resource for historians seeking to explore the activities of those working behind the scenes of law reform processes and to consider histories of law reform from alternative perspectives that reflect upon more subtle influences rather than simply the statute that passed or the case that succeeded. During most of the time the MWA was active, there were few major legislative reforms, but there had been a major shift in perspective about women’s legal status in marriage. As the MWA observed in 1964, the language of partnership had slipped into the vocabulary, which they saw themselves as having contributed to: ‘we have created by propaganda and agitation a public opinion that marriage is a partnership’.

MWA Annual General Report, 10 June 1964, 5MWA/3/1, The Women’s Library.

The work of the MWA therefore is significant. It gave a platform to a demographic of women typically ignored: middle-aged housewives. By connecting equal pay outside the home with equal partnership inside it, the formation of the MWA was a turning point in the direction of the women’s movement. And, perhaps most significantly, it called attention to the need to value unpaid care and housework, an issue feminists continue to grapple with today.

Quiet Revolutionaries: The Married Women’s Association and Family Law is available now from Hart Publishing, Bloomsbury.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Thank you to the author for providing images from The Women’s Library and LSE Library for kind permission to utilise them.