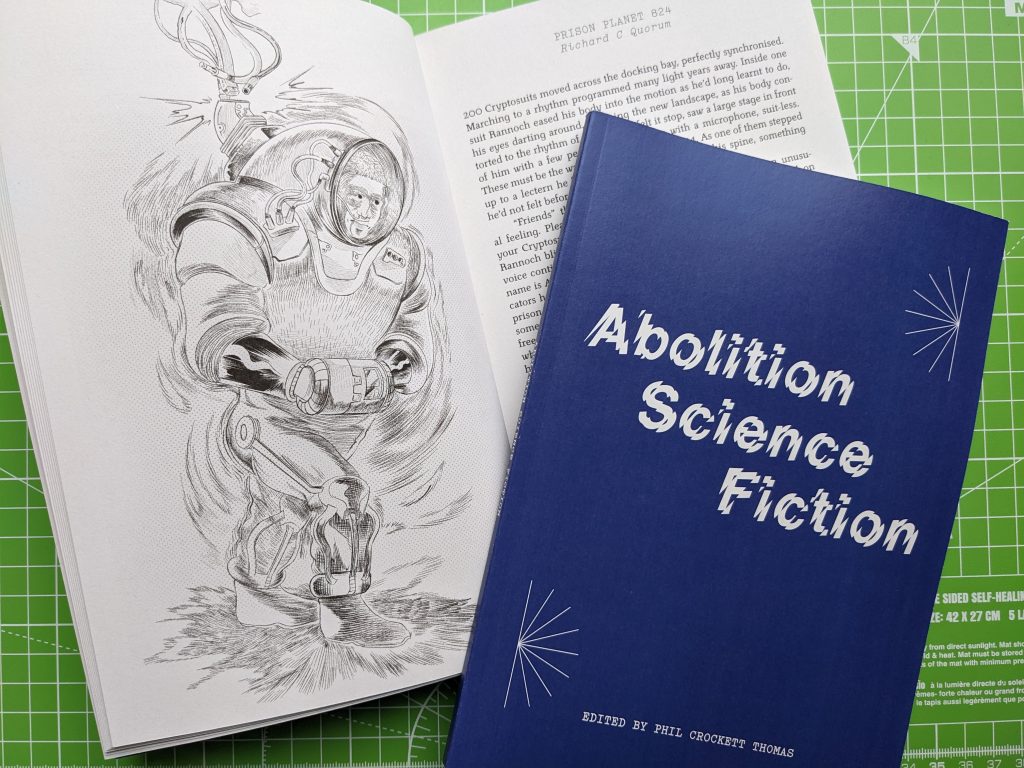

In this author Q&A, Rémy-Paulin Twahirwa speaks to editor Phil Crockett Thomas and contributors about their recent collection, Abolition Science Fiction, a collection of short science fiction stories written by activists and scholars involved in prison abolition and transformative justice in the UK.

Since the sparks launched by the #BlackLivesMatter movement, a growing interest in abolitionism has translated into the publication of many works on this theme, including We Do This ‘Til We Free Us, Change Everything, Against Borders and Abolition. Feminism. Now. Nevertheless, many critiques still depict abolition as an ‘alien and unthinkable idea’. Rémy-Paulin Twahirwa speaks to editor Phil Crockett Thomas and contributors to Abolition Science Fiction (2022), a collection of stories and discussions exploring worlds and futures in which prisons, policing and state-sanctioned violence are challenged by new ways to deal with harm and conflict.

Q: Could you introduce your book and the context in which it originated?

Phil: Abolition Science Fiction is a collection of short science fiction stories written by activists and scholars involved in prison abolition and transformative justice in the UK (you can download it for free at abolitionscifi.org). It came out of a fellowship research project called Prison Break, funded by the Independent Social Research Foundation. Alongside the stories are extracts from our discussions at the workshops where we wrote and shared the stories. There are also creative writing exercises and discussion prompts to help readers explore ideas about abolition and transformative justice in creative ways, and some beautiful illustrations by Nat Walpole.

In terms of the idea that abolition is ‘alien and unthinkable’, this book is a small contribution towards making abolition thinkable via the exploration of alien worlds! The stories are not all explicitly about prison abolition, but they explore the underlying question of how we can live well together, tackling complex topics like violence, revenge, responsibility, care and community. They can help us imagine a future where we respond to harm without exclusion and punishment, illustrating Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s contention that ‘abolition requires that we change one thing: everything.’

Q: How were the workshops conducted?

Phil: Because participants came from across the UK, some of the workshops took place online and some in person. We combined reading extracts from existing sci fi that explores justice issues in provocative ways, like Claire North’s 84k and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, with discussions, collective mapping and creative writing exercises. Some exercises focused on justice themes, some were just for fun and some focused on developing writing techniques like sensory description or creating scenes. I then supported the people who wanted to finish their stories and we had an online symposium where we shared and discussed our writing. Everyone who took part in the workshops was self-selecting: because participating in research can feel quite coercive, it felt important to only work with people who wanted to be there! Thomas Abercromby, an artist, curator and activist that I’d worked with as part of his School of Abolition project in Glasgow (where I live), also invited me to run an open workshop at Market Gallery. Some people who came to that ended up being part of the book. From my perspective, this was an amazing experience, one of the most rewarding and exciting processes of collective knowledge-making and sharing I’ve had.

Q: In your book, you engage in what Mariame Kaba and Kelly Wayes call ‘radical imagining’ (Lola Olufemi refers to this as ‘imagining otherwise’; adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha propose ‘visionary fiction’). Ultimately, you borrow Tom Moylan’s ‘critical utopia’ to describe your work. What does ‘critical utopia’ mean for you and how does it manifest in your book?

Phil: All the people you’ve just mentioned are an inspiration. I agree that we can gain a lot from nurturing a space to imagine differently, not only in terms of insight and strategy, but also in terms of hope and fostering a sense of connectedness to others struggling to make the world a better place. When I was designing the project I knew I wouldn’t have long to work with people and worried that putting them on the spot and inviting them to imagine a more just future, or a future in which there is no longer prisons or punishment, might be overwhelming! As Angela Davis reminds us, prisons are so embedded in society that it’s very hard to imagine life without them.

Because of the epic scale of the task, I found ‘critical utopia’ a useful concept because it acts as a reminder that utopia doesn’t have to be heaven. In fact, contemporary readers tend not to believe utopias in which everything is perfect (they also usually make for less interesting and compelling stories). Moylan coined the phrase to describe how sci fi authors in the 1970s were able to recuperate utopia after the horrors of Nazism and Stalinism. Novels like Ursula K Le Guin’s The Dispossessed ditch the idea of utopia as a blueprint and don’t shy away from discussing the dark side or grey of utopian societies. This makes them much more useful when we think about how our own messy, complex world could be made better.

Q: In ‘The Monument’, written by Dave, a former police officer is sent to protect a monument honouring the victory of the Abolitionists and the ‘end of policing’. However, policing seems to have survived its own end as the protagonist is now a ‘warden’ protecting the Abolitionist monument. Koshka comments on this story by highlighting how abolitionism might be hijacked by ‘respectability politics’. Why do abolitionists need to think critically about the after and afterlife of policing and carcerality?

Dave: I was concerned not so much with what comes after policing as what runs alongside it. I think it’s helpful to think of the police as part of a wider system of state functions which all work together to maintain capitalist society and to be attentive to the continuities between policing and other ‘public services’ (even when addressing this might become a little uncomfortable). If you assign people the job of tackling antisocial behaviour in a public space, those people become de facto cops because that is essentially a policing operation, even if not carried out by police officers.

Koshka: This is not just about an imagined future but what is happening here and now; I would add that the forms of policing we should be concerned with extend beyond the state. We see social policing going on every day when communities, families, people on the street or on Twitter exert pressure to conform to ‘the norm’ through shaming, attacking or ostracising people who are seen as having transgressed in some way. Like more obvious forms of social control enacted by the state, social policing is about inflicting suffering on people as punishment for non-conformity. It repeats the dehumanising logic of criminalisation in marking some people as unworthy of care and concern if they are suspected to have done something wrong. ‘Respectability politics’ is about disavowing and dissociating yourself from people or groups who are marked as ‘bad’, ‘deviant’, ‘violent’ or ‘criminal’. This is self-defeating for radical politics because these labels are so frequently and readily applied to people who cannot or will not conform to dominant ways of doing things. Even abolitionists can get stuck in these punitive and dehumanising ways of thinking.

Q: In Dear Science, Katherine McKittrick suggests that ‘theory [is] a form of storytelling. Stories and storytelling signal the fictive work of theory’. What is the contribution of books like Abolition Science Fiction in thinking differently or creatively about abolition?

Phil: Fictional representations are one of the key ways we know the world beyond direct experience, so we have to take them seriously. One of the project participants commented that he had learnt more about anarchism from reading The Dispossessed than any work of theory! I think McKittrick is rightly putting theory back in its place as one of the many valid and productive ways of knowing and telling about the world, fiction being another. In terms of the relationship between them, they have lots in common, but also different strengths and affordances. If you get blocked or stuck working on a problem via a theoretical approach (revenge versus justice as a response to harm, for example), you might find it helpful to approach the same problem via fictioning and vice versa.

Q: How did you engage with your own positionality in writing this book?

Phil: A lot of people come to abolition and transformative justice via experiences of harm or criminal justice which may have been traumatising. I didn’t invite people to disclose anything about their backgrounds because I didn’t want people to feel compelled to revisit these experiences. In terms of positionality, whatever their experience of criminal justice, everyone came to the project as someone who had engaged deeply with abolition and justice issues. This knowledge and experience came through in the fiction and poetry that people wrote because we tend to write about our preoccupations and experiences that feel significant or memorable. That’s at the heart of why I love using fiction as a research method: knowledge bubbles to the surface of the text, so it feels a less extractive way of working with people, especially those who might have stigmatised knowledge.

Q: Abolition Science Fiction is introduced as the fruit of collective work. How did you work together to create the collection?

Phil: Although I edited the book, it could only exist as the product of collective knowledge and labour. One of the places that collaborative projects often fall short of their ideals is on who gets paid for their labour. I had the budget to pay myself a wage and to pay everyone to attend the workshops and develop their writing, but not enough to pay them to co-edit a book. So, I had the pleasure of listening back to the recordings of our workshop and transcribing the conversations. Everyone who wasn’t directly quoted still contributed a great deal to our collective understanding. I brought the draft back to the contributors which led to some changes, but mostly people seemed happy with it. I am honoured that the contributors allowed me to include moments of and their reflections on vulnerability in the text. It’s been really rewarding hearing from participants that the project has inspired them to keep writing fiction, and from readers about how the stories moved them. I’m so grateful to everyone who gave the project their time. I hope your readers enjoy the book.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Rémy-Paulin Twahirwa.

Permission to use the feature image was kindly provided by Phil Crockett Thomas.