In Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It, Janina Ramirez reappraises the status of women in the Middle Ages by presenting the lives of several notable women who have been omitted from or underrepresented in histories of the period. Through her engaging storytelling about an eclectic assemblage of women, Ramirez persuades readers to rethink received ideas of women in the Middle Ages as disempowered, insignificant figures, writes Meaghan Allen.

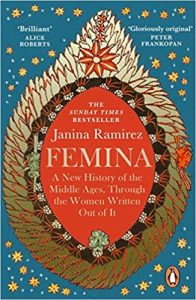

Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It. Janina Ramirez. Penguin. 2023

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

In the royal collections of Wawel Cathedral is an alms purse that once belonged to Jadwiga of Poland (c.1373—1399). The delicate object humanises Jadwiga by sharing her taste in fashion and design, her Christian devotion to the poor, and her elevated status. Dr Janina Ramirez, in her new book Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It, uses this item as a point of contact to Jadwiga, the purse’s rich embroidery functioning as symbolic threads narrating the story of Rex Jadwiga, the one and only female ‘king’ of Poland and primary establisher of Jagiellonian University, and Jadwiga the woman. Since her death, Jadwiga has been invoked for nationalist purposes rather than for her accomplishments as an intelligent female ruler, her piety and image as a paragon of virtue overshadowing her history-altering life. Compassionately reinterpreted here, Jadwiga is revealed as a remarkable woman, who, when placed alongside other women, retells a misunderstood and misremembered medieval past.

In the royal collections of Wawel Cathedral is an alms purse that once belonged to Jadwiga of Poland (c.1373—1399). The delicate object humanises Jadwiga by sharing her taste in fashion and design, her Christian devotion to the poor, and her elevated status. Dr Janina Ramirez, in her new book Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It, uses this item as a point of contact to Jadwiga, the purse’s rich embroidery functioning as symbolic threads narrating the story of Rex Jadwiga, the one and only female ‘king’ of Poland and primary establisher of Jagiellonian University, and Jadwiga the woman. Since her death, Jadwiga has been invoked for nationalist purposes rather than for her accomplishments as an intelligent female ruler, her piety and image as a paragon of virtue overshadowing her history-altering life. Compassionately reinterpreted here, Jadwiga is revealed as a remarkable woman, who, when placed alongside other women, retells a misunderstood and misremembered medieval past.

In Femina, Ramirez—a cultural historian, author, and broadcaster— intends to re-evaluate the status of women in the Middle Ages whose names have been ‘struck from the historical record due to the one word annotated beside them – FEMINA.’ An ambitious project, Ramirez orients each chapter around a particular theme and figure placing the past and present beside one another using modern scientific discoveries and cultural artefacts to provide contextual information for the subject she is discussing. Careful to underline that she is not re-writing history but rather shifting the focus from men to women, Femina’s overarching goal is to use the visible – physical artefacts – to reveal the seemingly invisible – women. Ramirez does not dwell upon obvious candidates such as Joan of Arc or Eleanor of Aquitaine. Focus is instead turned to an early medieval princess, known as the ‘Loftus Princess’, buried with an extraordinary cloisonné necklace; a Swedish woman buried with an axe, quiver of arrows, spears, and sword known as the ‘Birka Warrior’; the anonymous nuns who painstakingly stitched the Bayeux Tapestry; and rebellious (potentially heretical) Cathar spies.

One of the most memorable (and timely) figures Ramirez uses is Emily Wilding Davison, a devoted suffragette who threw herself in front of King George V’s horse Anmer at the Epsom Derby on June 4, 1903. Davison’s radical actions on behalf of the suffragette movement are presented as interwoven with her background as an Oxford trained medieval scholar, her (un)intended martyrdom a protest against misogynistic Victorian and Edwardian oppression which she viewed as a step back from a medieval era rich in diversity and populated by powerful women. Channelling Davison, Ramirez searches for inspiring female voices from the medieval world that have been supressed. This ‘over-writing’ of women, where male authors write the visions, words, and ideas of female intellectuals for a primarily male audience, has participated in the centuries-long erasure of the female voice. A main objective of Femina, then, is to reappraise history and re-orient women’s place in it, from the margins into centrality. As such, queerness, in its broadest sense as that which is eccentric, peculiar, or outside of, is at the heart of Femina. Often misunderstood as a ‘dark’ or ‘barbaric’ age, Ramirez repeatedly shows how the Middle Ages were incredibly diverse politically, geographically, theologically, and socially.

Ramirez’s final chapter ‘Exceptional and Outcast’ shares the research of Dr Rebecca Redfern. Through isotope analysis on skeletons found in the East Smithfield Black Death burial ground, Redfern discovered that many of the bones belong to people from outside London including Wales, Devon and Cornwall, and the Western Isles of Scotland, with twenty-nine percent classified as Asian, African, or dual heritage. To compare, the 2021 London census reported around sixty percent of the population as white and the remaining forty percent as Asian, Black, mixed, and other, encouraging a re-evaluation of London’s medieval streets as similarly cosmopolitan and diverse. Particular attention is drawn to the skeleton of a Black African woman whose teeth, essential for isotope analysis, lack the enamel pitting caused by the Great Famine of 1315-1322 that affected much of Northern Europe. As ancient DNA genome sequencing and forensic analysis classify this woman as coming from African heritage, Redfern and Ramirez conclude she spent her early years in fourteenth-century Africa. While the enslaved or free status of this woman is unclear, her skeleton’s rotator cuff disease and spinal degeneration coincide with the skeletal damage found throughout the East Smithfield excavation. Overall, the analysis suggests she travelled to London from Africa and was subject to the same harsh living conditions experienced by many working-class fourteenth-century workers. The East Smithfield skeleton is an exciting example of science merging with history to literally unearth the buried reality of migration and diversity during the Middle Ages.

Ramirez makes sure to include individuals not only geographically diverse, but also figures who presented themselves and lived in ways that challenged societal and cultural norms regarding gender, sex, and identity. Femina concludes with the story of Eleanor, a fourteenth-century sex worker arrested for acts of sodomy and prostitution. The case originally reported Yorkshireman John Britby participating in ‘the most nefarious and ignominious vice’ with ‘John Rykener, calling [himself] Eleanor, having been detected in woman’s clothing.’ Although it does not appear Eleanor was prosecuted for either crime, their testimony evinces involvement with members of the clergy, monks, and nuns, suggesting that their arrest was about moral corruption by high-status individuals rather than prostitution or sodomy. Throughout the trial, Eleanor shares how they had sex with men and women, using their job as a barmaid, seamstress, and prostitute to acquire clients. As the only surviving legal document from late-medieval England to document same-sex intercourse, Eleanor’s trial discloses how the scribes struggled to find suitable terms to express the sexual and gendered aspects of the case. The marginal and queer existence of Eleanor, whose testimony radically subverts accepted societal norms, reveals that complex humans who transgress and subvert sexual and/or gender expectations have been around for a long time.

A wonderful storyteller, Ramirez’s enthusiasm is contagious throughout Femina. Aside from the individuals discussed above, Ramirez also visits well-known extraordinary women like Hildegard of Bingen (1098—1179), the renowned twelfth-century abbess, scholar, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and medical scientist, and the ever-eccentric Christian mystic Margery Kempe (1373—c. 1438). For a non-medievalist audience, Femina is eye-opening and thrilling, a testament to women’s significance throughout history. But to anyone familiar with the Middle Ages, some of Ramirez’s strategies feel a touch cliché or expected. There is an irking sense that these prominent women overshadow the over-written or simply forgotten women that make Femina so wonderful. Regardless, it is a well-researched and accessible (if at times clunky) labour of love. To endeavour writing a history about those who have been silenced is admirable, and maybe it is impossible to ignore those who somehow managed to have a presence and voice in their own times. But hopefully, someday, a silent or secret history can be written completely with unknown or erased figures, a possibility FEMINA has enticingly introduced.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Main Image Credit: ‘The Unicorn Surrenders to a Maiden’ from the Unicorn Tapestries-Met Museum, French (cartoon)/South Netherlandish (woven) via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.