My Life in Fragments presents the life and thought of the late sociologist Zygmunt Bauman through an assemblage of letters he wrote to his daughters. Combining biography and broader reflections on the pressing issues of our time, this edited collection provides a sharp, rewarding insight into one of recent history’s most renowned thinkers, writes Danny Dorling.

My Life in Fragments. Zygmunt Bauman, edited by Izabela Wagner and translated from the Polish by Katarzyna Bartoszyńska, Paulina Bożek and Leigh Mueller. Polity. 2023.

Six years after his death, Zygmunt Bauman can still eviscerate – disembowel the claims of others and skin them of their intellectual pretensions. The penultimate chapter of this collection of older writings, translated from Polish, concludes with his “Last Memories”, revised in 2016 – less than a year before his death. He accuses Slavoj Žižek of falsifying the reality of communism (161), of playing with fire, and states, “I am amazed (and angered!) by the widespread tendency to consider Žižek a left-wing person” (223-226). As he was dying, Bauman concerned himself with what the young might come to believe, and whose call they might mistakenly follow. This edited collection is his parting shot. Often deadly accurate, it is well worth reading.

Six years after his death, Zygmunt Bauman can still eviscerate – disembowel the claims of others and skin them of their intellectual pretensions. The penultimate chapter of this collection of older writings, translated from Polish, concludes with his “Last Memories”, revised in 2016 – less than a year before his death. He accuses Slavoj Žižek of falsifying the reality of communism (161), of playing with fire, and states, “I am amazed (and angered!) by the widespread tendency to consider Žižek a left-wing person” (223-226). As he was dying, Bauman concerned himself with what the young might come to believe, and whose call they might mistakenly follow. This edited collection is his parting shot. Often deadly accurate, it is well worth reading.

Six years after his death, Zygmunt Bauman can still eviscerate – disembowel the claims of others and skin them of their intellectual pretensions.

Born in 1925 in Poznań, Poland, Bauman became one of the best-known sociologists in the world. He only ever applied for one academic job, shortly after World War Two, in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Warsaw. It was his first and last ever job application. After that “there were only invitations” (134). Forced to flee Poland during its antisemitic campaign in 1968, he went first to Tel Aviv University and ended up working at the University of Leeds. He wrote many books of which the best known are the Liquid series, including: Modernity (2000), Love (2003), Life (2005), Fear (2006), Times (2006), Culture (2011), and Evil (2016).

The first 100 pages of his latest, posthumous, writings concern his childhood. Many in young Zygmunt’s neighbourhoods, including his schoolteachers, were antisemitic, especially his teacher of geography (71). Despite this, as a child refugee he says: “my love of geography came in handy (Romer’s Atlas was the only treasure that I was able to preserve and keep whole in my endless wanderings; I slept clutching it in my arms)” (86). He had to abandon his atlas shortly after the barracks he was staying in was machine-gunned from the air (90-91).

By age 18, Bauman was a soldier, commanding 50 others (106). By 19 he was a second lieutenant in the Polish army and was awarded the Cross of Valour in 1945 for taking Kołobrzeg and fighting “against the patriotic underground” (147). However, not once in this book does he mention how many people he killed, or what that felt like, and how it affected him. He was made a child soldier shortly after 2 September 1939, when the train his family fled on was attacked from the air (76) – that was the second day of World War Two. Had there been no war, he would most likely have become a physicist. Instead, he turned to sociology, and to public writing.

He was made a child soldier shortly after 2 September 1939, when the train his family fled on was attacked from the air (76) – that was the second day of World War Two. Had there been no war, he would most likely have become a physicist. Instead, he turned to sociology, and to public writing.

Bauman could not “…live without thinking; I do not know how to think without writing” (30). His books have been “published in more than thirty languages beside Polish (and I will brag: these books are quite numerous)” (161). He writes of hope: “Hope wanders to that eternity that awaits us after death, before us. We trail behind it” (33). He approves of those who promote hope, including Václav Havel, Jan Józef Lipski and Jacek Kuroń, who all lowered “…the price we now need to pay for hope, courage and stubbornness” (187), and regrets he did not try harder during his life to emulate them.

As a child Bauman was intoxicated by socialist dreams of a future Poland, “…for everybody, however weak and wan. A country without hunger, misery and unemployment. A country in which one man’s success would not mean another man’s defeat…” (99-100). In young adulthood he joined and then rejected the communists. He was a lifelong socialist.

As a very old man he wrote: ‘Whether we realize it or not, whether we want it to be so or not, we carry responsibility for what will happen to all of us together. But as long as we do not take this fact into account, and as long as we continue to behave as if it were not so, both we and those around us are, so to speak, the ‘playthings of fate’. We are not free. Liberation comes only when we decide to transform fate into calling; when, in other words, we accept responsibility for that responsibility we bear in any case, and from which we cannot free ourselves; which we can at most forget or trivialize, making sure that our memory of this responsibility does not guide our actions and thus favouring enslavement over freedom” (196).

Even the sixty-word sentences are worth reading. “We live twice” he says, first living and then narrating the experience, a possible “ticket to eternity” (10). Unless we leave it too late and become a medically cultivated “cabbage,” as he appeared to fear for himself (15). At times, though, the multiple cross-references to famous philosophers can grate. Wittgenstein’s lion roars (incomprehensively) outside Plato’s cave, the dark from which the owl of Minerva emerges (at dusk); all in the space of three pages (25-28).

‘We live twice’ he says, first living and then narrating the experience, a possible ‘ticket to eternity’

Stronger criticisms can be made. For all of young Zygmunt’s love of a schoolchild’s atlas, he never let his imagination wander far from Europe. Had he looked more closely towards Australasia, the Americas, or Africa, he might not have suggested that: “We, the Jews, supplied the world with the archetype of suffering; perhaps in that lies our greatest contribution to striving after moral perfection” (156); or written of “Kolyma [in North East Siberia] and Dachau, those laboratories in which the limits of human enslavement and dehumanisation had been investigated… [or that] Survivor’s syndrome is hereditary; each generation passes on the poisoned fruits of the bygone martyrdom” (163-164). This may be true, but if so, the vast majority of the world’s population would still suffer from the syndrome – not merely the self-declared European archetypes.

Had he looked more closely towards Australasia, the Americas, or Africa, he might not have suggested that: ‘We, the Jews, supplied the world with the archetype of suffering; perhaps in that lies our greatest contribution to striving after moral perfection’

One final oddity is how much more men feature than women, although Rosa Luxemburg is praised towards the end, and Bauman’s wife and daughters feature often. Perhaps there were too few women of note to write about? Or perhaps Zygmunt was concentrating too much on competing with the other boys? This book’s existence is as much a labour of love by women as by the man: Katarzyna Bartoszyńska who first translated it; Paulina Bożek and Leigh Mueller who assisted later in that task; Anna Sfard who undertook the final corrections to the writing; and Izabela Wagner who edited the work into a collection.

Bauman may have failed to install enough hope in his own life, but several years after his death he is well placed to warn against despair and ignorance, both today and into the future.

Just as when he was a soldier, it is men Bauman attacks most effectively, including, as mentioned above, some of the most useful, terse and apposite words written on the veneration of Slavoj Žižek. Bauman may have failed to install enough hope in his own life, but several years after his death, he is well placed to warn against despair and ignorance, both today and into the future. The value of his books will not last an eternity – but they will continue to be read long enough. My Life in Fragments is among the best of them.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

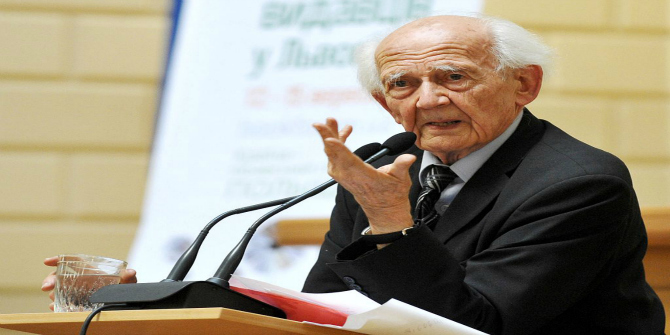

Image Credit: Zygmunt Bauman, by M. Oliva Soto via Narodowy Instytut Audiowizualny (CC BY-SA 2.0)

An excellent account of Bauman’s memoir. I have a short TLS review of the book out on November 3.