In The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World, Tim Marshall analyses the geopolitical dynamics and consequences of space exploration. According to Gary Wilson, the book is an illuminating insight into the political geography of space and the dynamics between world powers as they continue to expand the space frontier.

The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World. Tim Marshall. Elliott & Thompson. 2023.

While Tim Marshall’s previous works have firmly established him as a prominent authority on the politics of geography, in this new book he enters uncharted territory: an appraisal of the geopolitical dynamics and consequences of space exploration. In a series of earlier books Marshall considered the impact of geography on the possibilities and limitations of the projection of national power in some of the world’s political hotspots. The Future of Geography breaks new ground by probing how major world powers’ activities in space may come to shape the future of world politics in (until recently) ways which could not have been envisaged.

While Tim Marshall’s previous works have firmly established him as a prominent authority on the politics of geography, in this new book he enters uncharted territory: an appraisal of the geopolitical dynamics and consequences of space exploration. In a series of earlier books Marshall considered the impact of geography on the possibilities and limitations of the projection of national power in some of the world’s political hotspots. The Future of Geography breaks new ground by probing how major world powers’ activities in space may come to shape the future of world politics in (until recently) ways which could not have been envisaged.

The Future of Geography begins with the premise that space is rapidly becoming an extension of earth, representing the latest arena for intense human competition. Although the book explores the space activities and objectives of a wide spectrum of states and other actors, Marshall makes clear from the outset that there are three main players to be aware of: China, the US and Russia.

Space is rapidly becoming an extension of earth, representing the latest arena for intense human competition.

The book is structured into three parts. The first of these is relatively brief and consists of two chapters which serve to provide useful context for the more substantive treatment of space activity found in part two. In chapter one Marshall traces interest in space back to the earliest recorded historical periods, noting that there is a long history of “studying stars,” stone circles and similar (phenomena perceived as otherworldly or mysterious). Beginning with the Babylonians, he charts astronomical advances through Greek and Roman times into the twentieth century, referencing the scientific contributions of the likes of Copernicus, Galileo and Newton along the way. In the second chapter, Marshall identifies the origins of modern space exploration in Germany’s wartime rocket development programme, before proceeding to explain the importance of the Cold War in generating further advances in space as part of the arms race between the US and the Soviet Union. A string of Soviet “firsts” in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminated in Yuri Gagarin being the first man in space, which lead to huge surges in American space budgets as they raced to put the first man on the moon.

A string of Soviet “firsts” in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminated in Yuri Gagarin being the first man in space, which lead to huge surges in American space budgets as they raced to put the first man on the moon.

Part Two of the book represents its substantive core. In its six chapters, Marshall first explores some of the general difficulties and tensions generated by modern space exploration, before appraising the space policies of the world’s major players in this arena. The geography of space cannot be understood in earthly terms and scales, but in chapter three Marshall presents a series of numerical markers which permit the reader to gain some sense of the enormity of distances in space. Although NASA regards space as beginning at 80 km, the International Space Station is located 400km into space, while medium and higher earth orbit extend the area for potential exploration yet further. Noting that over 80 countries have satellites in space, Marshall posits that “the idea that space is a global common is disappearing.”

Most existing international space treaties are regarded as outdated, products of the Cold War that fail to account for technological advances and the expansion of states with space-related aspirations.

This leads into chapter four’s consideration of efforts to regulate space by legal mechanisms. Most existing international space treaties are regarded as outdated, products of the Cold War that fail to account for technological advances and the expansion of states with space-related aspirations. At best, current space activity is governed by a series of non-binding, ad hoc agreements. Marshall lays out the various sources of potential scope for conflict or disagreement, including questions raised by the activities of private bodies in space and increased space debris from the deployment and destruction of satellites. While the need for new legal regimes to regulate and foster cooperation in space activity is accepted, such developments are hindered by the fact that the major three space powers agree on little.

China’s space programme is more militarised than the others and, despite being a slower starter in space exploration, now seeks to rival the International Space Station.

The following three chapters consider in turn the space policies of the three big space powers. China’s space programme is more militarised than the others and, despite being a slower starter in space exploration, now seeks to rival the International Space Station. It is the only country operating its own space station and is working with Russia on the creation of moon base. China established various “firsts” in space during the first decades of the twenty-first century, is home to over a hundred private space companies and has developed plans for the years ahead, including launching over 1,000 satellites within a decade. Within the US, space investment has fluctuated over time in accordance with its relative popularity. However, in 2019 the US launched a 16,000 strong Space Force and has invested heavily in early-warning satellites and laser weapons. While planning a lunar gateway space station, the US has collaborated increasingly with private firms such as Space X, the first company into space and which was contracted to build a lunar landing module. In contrast to initiatives taking place in China and the US, Marshall suggests that Russia’s “best days in cosmology look to be behind it.” However, Putin has sought to reinvigorate Russia’s space programme as tensions have increased between Russia and the West in recent years. Its efforts depend heavily on its cooperation with China, with Russia regarded as the junior partner in the alliance to undermine US superiority.

Putin has sought to reinvigorate Russia’s space programme as tensions have increased between Russia and the West in recent years. Its efforts depend heavily on its cooperation with China.

The emphasis on the big three powers should not overlook the fact that an increasing number of states have invested to some extent in space activity. A brief survey of some of these takes place in chapter eight, which considers the move towards regional space blocs, such as the US allied European Space Agency, within which Italy, Germany and France have all been major players. While states as varied as Japan and India, Israel and the UAE are all referenced in this overview, Marshall notes that nobody comes close to challenging the big three.

In the book’s final part Marshall ponders some of the possibilities for the future of space exploration. The penultimate chapter sees him present some hypothetical scenarios, which illustrate some of the potential sources of future conflict. He highlights the danger of pre-emptive strikes in space and potential for escalation of conflict in such a scenario, while the biggest threat is considered most likely to arise from competition between the US and China. The book concludes by acknowledging the commercial opportunities which exist in space, while observing the various practical difficulties which may limit the extent to which they represent realistic propositions.

The Future of Geography makes an important contribution to understanding the political geography of space exploration and its impact on relationships between the world’s major powers.

The Future of Geography makes an important contribution to understanding the political geography of space exploration and its impact on relationships between the world’s major powers. It is not always easy to engage with some of the space jargon deployed, which presumes a certain amount of knowledge of space terminology and factual knowledge. There is also scope for the impact of space activity on international relations to be drawn out in more specific terms on occasion, to more effectively illustrate the possible real-world effects it may come to have. However, in a challenging and problematic arena of international political activity, the book offers insights which further the appreciation of the political geography of space exploration and provide illuminating food for thought as to what the future of space may hold.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

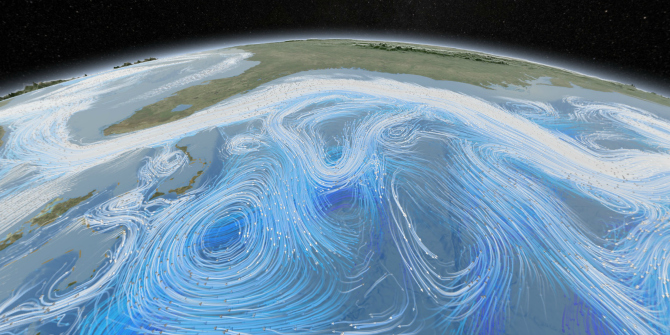

Image Credit: Artsiom P on Shutterstock.