In Industrial Policy in Turkey: Rise, Retreat and Return, Mina Toksoz, Mustafa Kutlay and William Hale analyse Turkey’s industrial policy over the past century, highlighting the interplay of global paradigms, macroeconomic stability and domestic institutional contexts. The book offers a timely analyses of industrial policy’s past and possible future trajectories, though it stops short of interrogating exactly how cultural, social, political and economic factors shape state-business relations and bureaucracy, writes M Kerem Coban.

Industrial Policy in Turkey: Rise, Retreat and Return. Edinburgh University Press. 2023.

Is industrial policy back? The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, or the 2016 UK industrial policy are only two contemporary examples. These policies seek to address value chain bottlenecks, as well as the question of how to “take back control” in manufacturing and key sectors, along with concerns about gaining or sustaining economic edge and autonomy

Is industrial policy back? The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, or the 2016 UK industrial policy are only two contemporary examples. These policies seek to address value chain bottlenecks, as well as the question of how to “take back control” in manufacturing and key sectors, along with concerns about gaining or sustaining economic edge and autonomy

In this context, the Turkish experience is illustrative for making sense of the trajectory of industrial policy in a major developing country. Mina Toksoz, Mustafa Kutlay and William Hale examine the evolution of industrial policy in Turkey. They present an accessible, detailed account of the trajectory and evolution of the policy since the establishment of the Republic, which argues that we had better study “the conditions under which state intervention works, rather than whether the state should intervene in the economy” (26, emphasis in original).

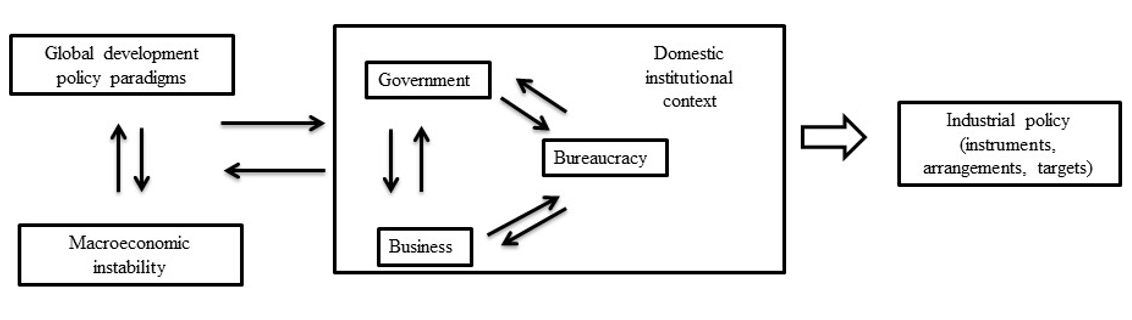

[The authors] suggest that effective industrial policy is the outcome of the interaction between global development policy paradigms, macroeconomic (in)stability, and the domestic institutional context.

The book is divided into five chapters. Chapter One discusses the political economy of industrial policy and sets out an analytical framework. The authors assert that analyses should go beyond dichotomies (eg, horizontal vs. vertical policies; export-led vs. import-substituting industrialisation) and that a broader understanding requires identifying the factors and conditions of effective industrial policy. They suggest that effective industrial policy is the outcome of the interaction between global development policy paradigms, macroeconomic (in)stability, and the domestic institutional context. Global development policy paradigms evolved from étatism of the 1930s, import-substituting industrialisation in the 1960s and the 1970s, neoliberalism of the 1980s, and the return of industrial policy after the 2008 Financial Crisis. Macroeconomic (in)stability drives (un)certainty regarding economic policies and instruments and the trajectory of economy, which, in turn, regulates investment decisions. Finally, the domestic institutional context concerns how state-society, or state-business, relations are structured, whether the state capacity is sufficient to resolve conflicts, discipline and coordinate actor behaviour, and whether bureaucracy has capabilities to formulate and implement policies. Figure 1 seeks to summarise the main argument of the book.

Chapter Two focuses on the longue durée between 1923 and 1980. From the ashes of incessant wars that ruined the already unsophisticated infrastructure and demographic challenge, the new Republic had to build a new nation. Yet the rise of the state interventionist era in the 1930s drove policymakers towards the first industrialisation plan and the opening of many industrial sites across the country. When the Democrat Party assumed power, the interventionist, planning-based industrial policy was scrutinised for liberalisation that even included state-owned enterprises to be released to set up their own prices (73).

At the same time, business was encouraged to invest. For example, the fruits of these included Otosan or BOSSA (75). Between 1960 and 1980, the authors underline the second planning period with the establishment of the State Planning Organisation (SPO). SPO boosted bureaucratic and planning capacity and capabilities for disciplined, systematic industrial policy during the era of import-substitution.

Between 1980 and 2000 […] Turkey shifted to export-led growth and liberalised trade and financial flows. These shifts had profound implications for bureaucracy

The third chapter examines demoted industrial policy between 1980 and 2000 when Turkey shifted to export-led growth and liberalised trade and financial flows. These shifts had profound implications for bureaucracy: SPO was sidelined, parallel bureaucratic networks of Ozal were implanted with the opening of new offices or agencies. Consequently, the role of state became less coherent, as political uncertainty driven by unstable coalitions eroded the market-shaping role of the state. The financial sector did not help industrial policy, since banks were dominantly financing chronic budget deficits during a period of high inflation (111). What is more, business, including Islamic conservative SMEs in Anatolia, reduced or ignored investments in manufacturing given the clientelist state-business relations that incentivised construction, real-estate development (115), emphasis in original). Finally, the external conditions were not disciplinary: accession to the Customs Union with the European Union and the World Trade Organization ruled out export support and import restricting measures, among other trade regulatory instruments.

The fourth chapter claims that industrial policy retreated between 2001 and 2009. The first years of this period was marked by political instability and a local systemic banking crisis and its resolution, and Justice and Development Party (AKP in Turkish) assumed power. During this period, industrial policy was dominated by institutionalisation of the regulatory state and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, the establishment of autonomous regulatory agencies and are structured banking sector. While the regulatory capacity of the state increased, privatisation and the regulation of the market were highly politicised. For example, “a major cycle of gas privatisation saw ‘politically connected persons’ winning fifteen out of nineteen metropolitan centres and serving 76 percent of the population” (161). In such a politically compromised setting, which was accompanied by the institutionalisation of the capital inflow-dependent credit-led growth model that prioritised “rent-thick” sectors, industrial policy could not flourish.

While the regulatory capacity of the state increased, privatisation and the regulation of the market were highly politicised.

The fifth chapter locates the policy within the global ideational and political economic context that marks the return of industrial policy in various forms. In line with policy documents such as the 11th Development Plan, horizontal measures, private and public R&D spending on high-tech initiatives, electric vehicle manufacturing attempt, and most notably the advancements in defence sector have constituted the revival of industrial policy. At the same time, the authors point to several challenges such as eroded academic research and quality and a lack of investment in ICT skills. Additionally, R&D subsidies or other industrial policy measures require thorough performance criteria and measurement to discipline actor behaviour and regulate the incentive structures.

Industrial Policy in Turkey is a timely contribution to the current debate. Its historical account and analysis of current policies, instruments, and the potential trajectory of industrial policy are its main strengths. Still, there are several caveats. First, the book’s framework is not systematic, which causes some confusion. For example, the book does not demonstrate a convincing link between the role and impact of autonomous agencies on industrial policy. Second, the book leaves the reader with more questions than answers, one of which relates to the effect of bureaucratic fragmentation in shaping industrial policy. Another is around the implications of state-business for bureaucracy, and consequently, industrial policy.

The book leaves the reader with more questions than answers, one of which relates to the effect of bureaucratic fragmentation in shaping industrial policy.

Third, the trajectory of industrial policy cannot be considered independently from the shifts in growth models. Yet the fact these shifts occur because the country depends on hard currency earnings for capital accumulation and to finance consumption and investments: Turkey either relies on capital flows or export earnings, in addition to tourism and (un)recorded (illicit) flows. Pendulums between these channels imply that the country cannot design and implement disciplined, systematic industrial policy. Put differently, there are macroeconomic and financial structural impediments against generating hard currency earnings. Industrial policy is one of the remedies, however, the macroeconomic and structural transformative consequences of the latest episode of emphasis on industrial policy and the export-driven growth experiment in Turkey are yet to be seen.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the book tends to relegate a core problem of coordination, long-term policy design and implementation to “governance issues”. Deeper cultural, social, political and economic factors determine the clientelist state-business relations and their effect on bureaucracy and bureaucratic autonomy. Such deeper ties have been masked by instrumentalised “democratisation reforms” or higher economic growth rates in the previous years. In this context, is the more critical problem the purposefully immobilised or challenged infrastructural power to coordinate societal actors? If that is true, then should we make interdisciplinary attempts to identify this problem’s core determinants?

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Chongsiri Chaitongngam on Shutterstock.