In A Crash Course on Crises, Markus K. Brunnermeier and Ricardo Reis survey the macroeconomics of financial crises, examining the before, during, and after stages of collapses through theoretical models and case studies. Though the book’s analysis is insightful, cogent and well-structured, Minh Dao suggests that the trade-off of depth for concision may leave some readers wanting.

In A Crash Course on Crises: Macroeconomic Concepts for Run-ups, Collapses, and Recoveries, Markus K. Brunnermeier and Ricardo Reis examine the three stages of “macro-financial” crises: before, during, and after the crisis events. The book takes a straightforward approach. First, the authors qualitatively explain an economic model, then detail one or two case examples based on the given abstract framework, rendering each chapter a self-contained unit.

With the main content of the book contained within 100 pages, A Crash Course on Crises, summarises and synthesises theoretical explanations on famous macro-financial crises case studies

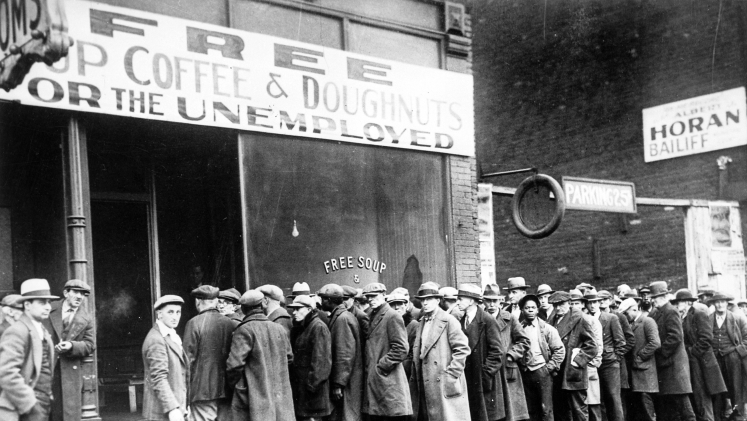

With the main content of the book contained within 100 pages, A Crash Course on Crises summarises and synthesises theoretical explanations on famous macro-financial crises case studies (eg, the Great Depression in the US in the 1920s and1930s, the Japanese Bubble of the 1980s and the European Debt Crisis in late 2009). The authors succinctly crystallise those theoretical analyses into a unifying theory of macro-financial crises through ten conceptual frameworks, one in each chapter. This macro-theory can be viewed from a chronological sequence as follows.

Before the run-up phase to a crisis, optimism leads to asset price bubbles because of the speculation from investors

First, before the run-up phase to a crisis, optimism leads to asset price bubbles because of the speculation from investors with different level of “sophistication” or rationality. In the authors’ words, we have two groups of sophisticated and momentum investors, ranging from fully to less rational, who are trying to get the most value from the growing bubbles by speculation, ie, guessing how others will behave. With the subsequent large and sudden capital inflows thanks to the bubble, a problem of capital misallocation can be seen within and across sectors. Simultaneously, modern banks can raise more funds as compared to traditional banks thanks to the wholesale funding component in the liabilities side of balance sheets. One common example of wholesale funding is interbank borrowing.

A discussion on how modern banks (especially European banks) run identifies three key features. First, banks can grow quickly by wholesale funds because, banks can borrow more money from other big corporations or banks rather than waiting for people to lodge their savings. Second, wholesale funds are fickle; there is a risk that other banks may suddenly stop lending. Third, this borrowing behaviour amplifies the fluctuation of prices (“asset-price cycle”). An example of this is when banks can borrow a lot of money quickly and therefore lend it out to people easily, which makes housing prices go up due to high demands for houses (upturn). If some people lose their jobs and default on their payments, banks suffer and they become more cautious to lend, making the housing prices go down due to declining demands as people cannot borrow like before (downturn).

In this section, it seems that the authors’ advice to “lean against credit-financed bubbles” (20) may be too general, like saying all bubbles are bad and we therefore should discourage them. We know that “bubbles” exist for some reasons, eg, creating wealth and spurring innovation . There is an argument that “macroprudential policy should optimally respond to building asset price bubbles non-monotonically depending on the underlying level of indebtedness.” In other words, what we should do is to monitor the stages of bubbles rather than wholly discouraging them.

A curious reader may also wonder how governmental fiscal policy can prevent asset price bubble, especially when the authors stop short after briefly mentioning “Modern banking requires changes in regulation” (35), and a deeper analysis into macroprudential policy may supplement these chapters, eg, Systemic Risk, Crises, and Macroprudential Regulation by Freixas, Laeven, and Peydró.

At the arrival of a crisis, a domino reaction happens when investors start to sell assets quickly, driving down the prices and in turn making harder to sell the assets.

Secondly, at the arrival of a crisis, a domino reaction happens when investors start to sell assets quickly, driving down the prices and in turn making harder to sell the assets. This results in a systematic failure in the financial market. Amid crises, it is practically impossible to distinguish solvency and liquidity, and knowing which is the driver can inform the policymakers how to respond. A phenomenon known as a “diabolic loop”, when banks hold sovereign bonds interacting with governmental fiscal policy of bailout in a way that continuously brings both down, can explain further how and why bailout policy may not have the intended consequence. Another important phenomenon during the financial crises is the capital flight to safety (eg, investors buying sovereign bonds of Germany or France).

Finally, at the recovery period or policy response phase, national fiscal policy in the form of reserve satiation, forward guidance, and quantitative easing (dubbed “unconventional”) can shed light on the role of central banks and what advanced economies have been doing to mitigate economic slowdowns. The Japanese case study in Chapter 10 is illuminating with regards to fiscal policy addressing the long economic slowdowns. Moreover, revisiting to equilibrium real interest rate, r* (ie, the interest rate accounting for inflation that is the optimum for the market of saving and borrowing) and fiscal policy in ending the Great Recession is aimed at reconciling neo-classical and Keynesian arguments on the nexus of savings and investment. The authors’ fresh take on this reconciliation lies in how they consider why “the recession comes with a financial crisis” (102-103), whereas both neo-classical and Keynesian proponents did not account for financial crisis.

The trade-off of keeping “the book mercifully short” (9) and the ambition of covering 10 key concepts (each of which could easily merit a whole book) means that it sacrifices depth of enquiry, and many historical details are excluded. This is justifiable, as the book is intended as a supplementary reading to Intermediate Macroeconomics (hence the “Crash Course” of its title) and they did reference the background of real-life examples in the notes at the end of each chapter. However, the decision to economise on detail does leave readers wanting, both those familiar with the case studies and those being introduced to them who might find the chapters disjointed. If readers then need to consult additional sources, this belies the authors’ claim to have written a self-contained book.

The trade-off of keeping ‘the book mercifully short’ and the ambition of covering 10 key concepts (each of which could easily merit a whole book) means that it sacrifices depth of enquiry, and many historical details are excluded.

While Brunnermeier and Reis describe their theoretical models qualitatively before going into case studies, qualitative explanations alone may create difficulties in interpreting some models illustrated by graphs – eg, bivariate models of exchange rates and recovery (85) explaining the endogenous relationship and equilibrium between investments and savings (domestic and foreign). The book would have benefitted from some simple algebra accompanying the qualitative explanations of graphs to illustrate how the relationship and/or equilibrium changes. This could have been achieved without having to resort to mathematical generalisation (which the authors opt to avoid so as not to further complicate the subject matter). Sometimes, a prudently moderate combination of qualitative and quantitative explanation can make economic concepts more accessible than either extreme approach, especially for the target audience possessing only “introductory economics” (8).

This book is a great companion to macroeconomics or macro-finance courses for students and policy experts.

All things considered, Brunnermeier and Reis deliver a cogent treatise on macro-financial crises. This book is a great companion to macroeconomics or macro-finance courses for students and policy experts. The audience that may enjoy the greatest benefit are those with a grasp of intermediate macroeconomic understanding, rather than being familiar only “with introductory economics”, as the authors suggest.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: gopixa on Shutterstock.