In Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Anne Case and Angus Deaton document the rising death rates from suicide, drug overdoses and alcoholic liver disease in the US, exploring what these ‘deaths of despair’ reveal about capitalism and the healthcare system. Making a compelling case for exploring these deaths of despair and their implications, this stimulating and thought-provoking book belongs on the reading list of all of us who are facing difficulties and uncertainties in our everyday lives, writes Wannaphong Durongkaveroj.

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Anne Case and Angus Deaton. Princeton University Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

In Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, economist Anne Case and Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton document the rising death rates from suicide, drug overdoses and alcoholic liver disease — what they term ‘deaths of despair’ — in the United States. Every year more than 100,000 Americans die from these three kinds of deaths. The authors criticise aspects of American capitalism and the healthcare industry and question how globalisation and technological progress are contributing to the US economy and society.

Following a succinct introduction, the book contains sixteen chapters. Three of these deal with the improvement in health in the United States in the twentieth century and the reverse trend among middle-aged white non-Hispanic Americans in the early twenty-first century (Chapters One to Three). The next six chapters thoroughly analyse the pattern of deaths driven by suicide, drugs and alcohol (Chapters Four to Nine). Chapters Ten to Twelve discuss how poverty, economic crises, declining wages and the destruction of a way of life (shaped by family, community and religion) contribute to these deaths of despair. The last four chapters explore the role of American capitalism and the healthcare system in this epidemic.

Similar to other rich countries, the US has seen continuous improvements in human health during the twentieth century. People lived longer and the risk of dying (the mortality rate) declined. The mortality rate for midlife white people aged between 45 and 54 in the US dramatically declined between 1990 and 2000. However, things came apart at the beginning of the twenty-first century. While midlife mortality continued to fall in other rich countries (for example, France and Britain), mortality for US white non-Hispanic Americans stopped falling and began to rise. Case and Deaton describe this situation as ‘important, awful, and unexpected’. It is important to note that Hispanics and African Americans, who are poorer on average than non-Hispanics, do not share this worrying trend over the same period. ‘Deaths of despair’ therefore particularly concerns middle-aged white people.

Image Credit: Photo by Sholto Ramsay on Unsplash

The big issue explored in this book is what middle-aged white Americans are dying from. Three key players are drug overdoses, suicides and alcoholic liver disease and cirrhosis. The US has seen a rapid rise in these deaths in almost all states since 1999. The three causes of deaths are related but they share one common feature — they reflect great unhappiness with life among Americans. Unlike deaths from an epidemic driven by a virus or a bacterium, people are doing this to themselves. In addition, there have been rapid increases in deaths of despair among younger white Americans, especially from drug overdoses and suicides. This epidemic is worsened by disrupted progress against deaths associated with heart failure and obesity.

However, not every midlife white American is facing the same threat. Since the early 1990s, there has been a growing gap in mortality between education groups. The likelihood of dying from deaths of despair is particularly high among those without a four-year college degree. Death, sickness (such as morbidity and mental distress) and pain also go together, especially among less educated white Americans. The book highlights the role of education in peoples’ lives. In the context of the US, higher education means more money. This is reflected in the so-called ‘earnings premium’ — the difference in income between those with a bachelor’s degree or higher and those who left school with a high school diploma. This tells us about the limited opportunities for those without a bachelor’s degree in the labour market, driven by several factors including globalisation and automation.

Many also believe that poverty or the 2008 Great Recession is central to a rapid increase in deaths of despair. Case and Deaton partly agree. The decline in income matters but what is more important is the long-term deterioration in opportunities for less educated Americans. Good jobs have become scarcer for this population and wages have fallen. Meanwhile, it is evident that there is a widening gap between the less and the more educated in marriage, child rearing, in religion, in social activities and participation in community. For example, from 1990 to 2018 those without a college degree saw a decline in marriage rates compared to those with a bachelor’s degree; those without a bachelor’s degree are also less likely to attend church weekly. Case and Deaton call the decline of family, community and religion ‘the destruction of a way of life’.

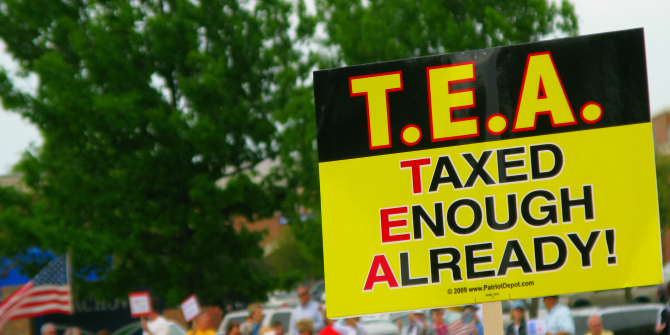

The situation is worsened by the expensive American healthcare system. The cost of American healthcare goes to hospitals, doctors as well as device and drug manufacturers. An increase in healthcare costs affects not just the ability for individuals to spend money on other things and save, or firms’ decisions to hire more. Pharmaceutical companies are also reaping profits from patients’ addictions and from pricing strategies that deny people access to medical advances. Some blame American capitalism for this tragic situation, but Case and Deaton believe in the power of competition and of free markets. However, they argue that American capitalism should be better monitored and regulated to ensure that markets, globalisation, innovation and migration work for people, not against them. The American safety net makes it worse because it has failed to adopt universal protections that provide insurance across all of society. Case and Deaton urge for universal insurance and controls over healthcare costs.

The hallmark of this book is the compelling case made for exploring deaths of despair and their causes. Economic concepts and data are carefully explained with clarity. As the book focuses on health, it is timely and provides implications for the COVID-19 pandemic.

I agree with Case and Deaton that income inequality in and of itself is not the fundamental problem when it comes to deaths of despair. However, there are other arguments about how rising income inequality can have detrimental effects on people’s well-being. Based on the work of the late Albert Hirschman, prolonged periods of inequality destroy hope and expectations for the future. This can result in the so-called ‘development disaster’ (collective political action driven by anger and frustration). Indeed, there are several empirical studies suggesting that living in an unequal society is associated with an increase in mistrust and anxiety about social status as well as a decrease in the overall well-being of individuals. An extension of the analysis to cover this issue may supplement the story in Deaths of Despair.

While Case and Deaton’s analysis of the impacts of globalisation and automation on deaths of despair is insightful, these two factors are century-old stories and require a new analytical framework to uncover their full implications. According to trade economist Richard Baldwin, the economy is currently disrupted by the so-called ‘globotics’ revolution (globalisation plus robotics). The issue is that these disrupt and displace workers in the service sectors. This change can happen very quickly and the outcomes on the economy are in favour of highly educated workers. The key issue relevant to deaths of despair is that it is likely that white-collar workers will join the despair that has been long experienced by blue-collar workers. Extending the story to also cover those who are highly educated, paid well and working in the service sectors and their ways of coping with the ever-changing nature of work could be a supplement to the book’s research.

Although this book is about American deaths of despair, it offers a valuable lesson for today’s developing countries. In the future when their economies further develop, resultant structural transformation will affect workers in these countries. Greater prosperity and greater life longevity in the last century are the two triumphs of humanity across the globe. But it is worrying to see increases in mortality from deaths of despair in rich countries like the US, especially among middle-aged white people in the past two decades. It is challenging, in terms of policy recommendations, to consider whether deaths of despair will be the next chapter for the developing world.

It would also be interesting to consider the book’s findings in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. So far, it is evident that the pandemic has resulted in an increase in deaths of despair in the name of non-COVID-19 excess deaths. Depression and alcohol use disorders are found to have increased during the outbreak of the virus.

In this stimulating and thought-provoking book, two distinguished economists offer more than an analysis of the mortality rates in the US and what is going wrong for its healthcare system. It belongs on the reading list of all of us who are facing difficulties and uncertainties in our everyday lives.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Hi, I am curious as to why the links “Albert Hirschman” and “mistrust and anxiety” are crossed out. Thanks for the great article!