In this interview with Anna D’Alton (LSE Review of Books), Jane Cholmeley discusses her new book, A Bookshop of One’s Own which tells the story of Silver Moon, the pioneering feminist bookshop she co-founded in 1984. Silver Moon opened on London’s Charing Cross Road as an underdog business and went on to become Europe’s largest shop of its kind and an iconic space for, and promoter of literature by, women.

Jane Cholmeley will speak about the book at an event hosted by LSE Library on Tuesday 11 June – find details and register to attend.

Q What motivated you to set up the Silver Moon Women’s Bookshop in 1984? Why was specialising in women’s, feminist and lesbian literature important?

Q What motivated you to set up the Silver Moon Women’s Bookshop in 1984? Why was specialising in women’s, feminist and lesbian literature important?

They say that redundancy is best treated as an opportunity rather than a setback, and so it was with us. My partner, Sue Butterworth, and I were both made redundant within six months of each other and needed work. We looked at our lives and the things that interested us – feminism, lesbian experience, women’s politics, and publishing. We thought first of starting a publishing house – Sue was an editor, I did finance and sales – but we didn’t have the money for it. So, we thought, with supreme arrogance, that we could open a bookshop even though we knew nothing about it.

Q: You describe a lively culture of radical publishing, including women’s and queer publishing, when you opened the shop. Where did this stem from?

Spare Rib (the feminist magazine) was set up in 1972, Virago (a feminist publisher) in 1973, Onlywomen Press in 1974, the Women’s Press in 1978 and others. A lot of this came out of the counterculture of the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. It also linked into the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements in America. There was a ferment of thinking, writing and activism and the publishers were publishing wonderful titles, though these books were being met by blockages en route to their audience. There was a tremendous amount of gatekeeping or a lack of interest in linking the author to the reader, and we thought a dedicated women’s bookshop could help to bridge that gap. It was a vibrant time when you felt you could do anything, you felt incredibly strong and energised because there was so much political activity going on and challenges to societal norms.

Out of the counterculture of the late ‘60s, early ‘70s […] there was a ferment of thinking, writing and activism and the publishers were publishing wonderful titles, though these books were being met by blockages en route to their audience.

Q In the 1980s, the Greater London Council (GLC) was progressive in its funding of projects by and for marginalised groups. How did this help you to open the shop?

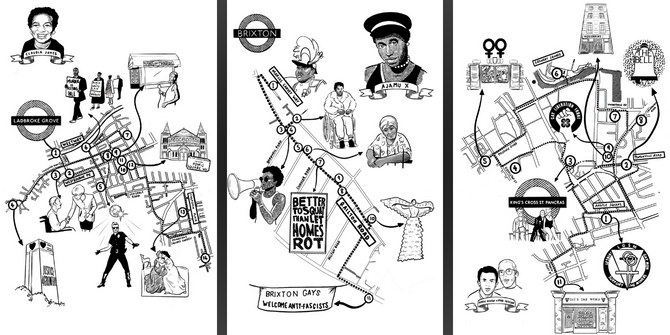

We’d been looking for premises for over a year when a friend alerted us to an ad in the Bookseller by the GLC advertising two shops for bookshop use only and offering a ten per cent rent discount. The spaces were on the Charing Cross Road – then the book-selling street in the country, even in Europe. The GLC wanted to keep alive bookselling tradition of the area, which attracted great tourism. They also wanted to make a difference in who had access to cultural money. Their position was that Britain was behind other European countries in spending on culture, and that they wanted to support groups who were underrepresented and underfunded – women, gay people, Black people, Asian people, disabled people.

The GLC knew that their existence was under threat from Thatcher (her government went on to abolish it in 1986) and they wanted to fund new projects in a way that would allow them to continue beyond their abolition. So, we put in our sealed tender, and our proposal about the shop’s mission, and were successful. The GLC said that Silver Moon was “a project of strategic importance”, which we thought was just wonderful.

Q: How did Thatcherite politics impact LGBTQ+ people and businesses like Silver Moon?

We opened in a hostile environment. Our opening date, 31 May 1984 was 51 days after the raid on Gay’s the Word bookshop (where Customs and Excise officers seized alleged “indecent material”). There were many attacks on the LGBTQ+ community, including Section 28, which banned the teaching “of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship” – those words still make me angry. We knew we were going into battle, but I like to misquote Dickens: it was the worst of times, it was the best of times. The more the government attacked us, the more the gay and lesbian community came together to fight back. It was a time of huge comradeship and very creative political resistance.

Our opening date, 31st May 1984 was 51 days after the raid on Gay’s the Word bookshop […] There were many attacks on the LGBTQ+ community, including Section 28

Q: Why do you argue that women running businesses that were both political and profitable was crucial to the Women’s Liberation movement?

I argue that because rather a lot of them failed. I’ve always had a horror of failure: I do admit to ambition, not for myself, but for something that I believe in. We weren’t interested in succeeding in capitalist terms per se, but in mission terms, and that necessarily involved paying your staff and suppliers properly and meeting the rent. There were also many people that wanted us to fail, and it was necessary to prove to them that as women, we could succeed.

Q: How did the shop function as a space for art and community?

The original idea was to have a bookshop and a café, which was also an art gallery to show the work of women. Unfortunately, the café didn’t justify itself financially, and we had to close it after about 18 months. However, we stocked a lot of non-book merchandise in the shop that became our art – T-shirts and gifts with artwork and quotes, like Eleanor Roosevelt’s “a woman is like a tea bag. You don’t know how strong she is until you put her in hot water.” There were Christmas cards with “the birth of a man who thinks he’s God isn’t such a rare event”.

Community formed in the shop because people just came to be there

Like most radical bookshops, we had a notice board with flats for rent, plumbers, electricians, driving instructors, consciousness raising groups, gigs, holiday lets that people would come in to peruse. Community formed in the shop because people just came to be there. There’s a piece in the book about somebody who came to London and didn’t really know anybody but used to come to us every lunchtime. She would sit, read and feel comfortable and safe knowing that she was in her space and was surrounded people who thought the same way she did. At one point we were even hailed by City Limits as “the best lesbian cruising venue in London on a Saturday morning”!

Q: What were the biggest challenges you faced running Silver Moon?

The most difficult thing was the balancing act between politics and profit, money and mission. For example, we had endless discussions in staff meetings about a book that someone felt was really important but wasn’t selling, to which I’d respond, how could it be really important if nobody’s reading it? One of the other areas in which this was a great tussle was mail order. Our community was very much beyond our geography, but back then there wasn’t any internet or e-mail. It was pen and paper and postage, and that was expensive. Our mailing list ended up at over 10,000 subscribers which was a lot of work. We had a community stretching from Aberdeen to Zennor, from Alaska to Zambia, but we had to ask is it making any money? For our politics it was the right thing to do, but was it profitable?

The most difficult thing was the balancing act between politics and profit, money and mission.

We wanted to pay our staff as well as we could, but retail is very badly paid. We had to keep a tight hold on the purse strings, but we would give out bonuses when we could. It was a balancing act of ensuring the shop was profitable and we could invest and progress without risking going bust.

Q: In the book, you draw not only on your own experience, but the records of employees, authors and customers of the shop. Why was this important to you?

I held onto all the documentation about Silver Moon, and in 2018, I started going through it to write an academic book. But it’s very difficult writing an academic book when you have Sue Butterworth, with her magnificent sense of humour, sitting on your shoulder, and when you have conundrums like, how can I write an academic book and put a dog (our shop dog Biff) in it? I realised I needed help, so I sought out 20 ex-staff members, sent them a questionnaire, and the response was completely wonderful. The book that I’d been writing was rather dry, and what they were coming back with were the best stories, tone, voice and humour that brought the shop to life. It seemed essential to put that in – we all worked together, so I think we all should tell our stories together. And it made it into a completely different, much more readable book.

Q: Silver Moon closed in November 2001. What are the greatest legacies and your proudest achievements from it?

Overall, in our time we put £15 million through the publishing and author economy. We were unbelievably privileged to welcome amazing authors like Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Angela Carter and Alice Walker for launches and readings. At that moment in the 1980s, those major Black American writers hadn’t been given any time in the UK. When they came to London, other shops weren’t interested in hosting them – they weren’t paying attention. Virago bought the UK rights to I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in 1984 for £1000 – they printed 6000 copies and sold them in two weeks. With Toni Morrison’s books, there were gaps of many years between US and UK publication, and it was only on her fourth book that there was simultaneous publication. A couple of years later she won the Nobel Prize. We had a fabulous time introducing the work of these wonderful women to the UK market.

The feeling that we had made women’s lives better, transformed their reading, transformed their lives – if we did anything like that, I feel honoured.

The other legacy was the customers. When we had to announce our closure, we invited customers to write their comments in a book, and it took me at least two years to open it because it was too emotional. There were comments like “This is where my life really started” and “You helped show me that I wasn’t alone. Thank you”. The feeling that we had made women’s lives better, transformed their reading, transformed their lives – if we did anything like that, I feel honoured. And last, but not least, we had a jolly good time doing it!

Note: This interview gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main image credit: The Silver Moon bookshop on the Charing Cross Road, courtesy of Jane Cholmeley.